The Carolingian Decline

To understand the significance of Hugh Capet’s coronation, we must first examine the political landscape of the time. The Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled the Frankish realms since the mid-8th century, was in decline. The last Carolingian king, Louis V, died childless in 987 at the young age of 20, leaving no clear heir to the throne.

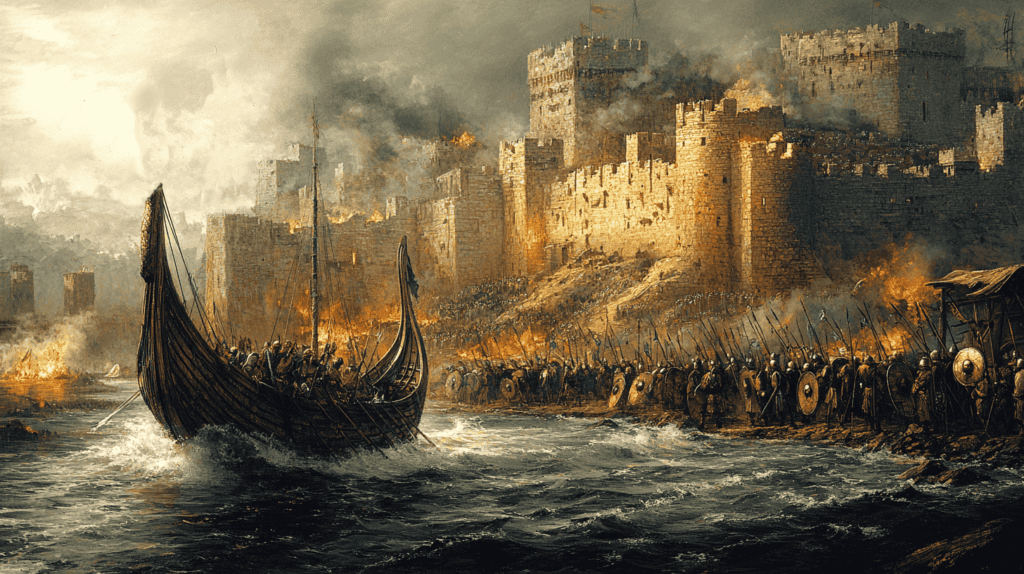

The Carolingian Empire, once a vast and powerful entity under Charlemagne, had fragmented into smaller kingdoms. The western Frankish realm, which would eventually become France, was struggling with internal conflicts and external threats. Viking invasions, in particular, had weakened the kingdom’s defenses and exposed the ineffectiveness of centralized Carolingian rule.

Hugh Capet: The Rise of a New Dynasty

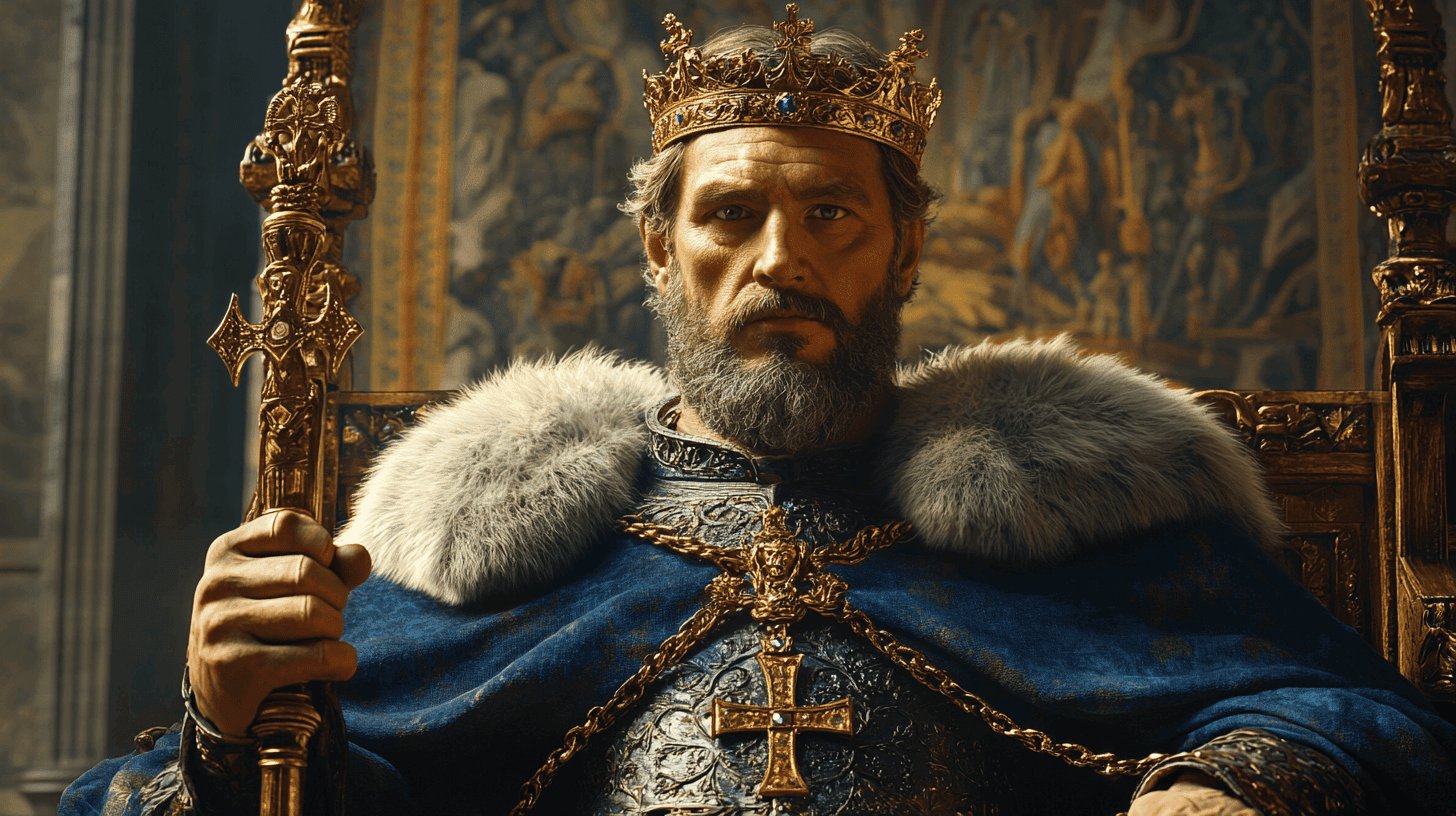

Hugh Capet was not a newcomer to the political scene. Born around 940, he was the eldest son of Hugh the Great, Duke of the Franks, and a powerful nobleman in his own right. Hugh Capet had inherited vast estates in the regions of Paris and Orléans, making him one of the most influential vassals in the kingdom

In the years leading up to his coronation, Hugh Capet had been actively involved in the political intrigues of the realm. From 978 to 986, he allied himself with the German emperors Otto II and Otto III, as well as with Adalberon, the influential Archbishop of Reims.

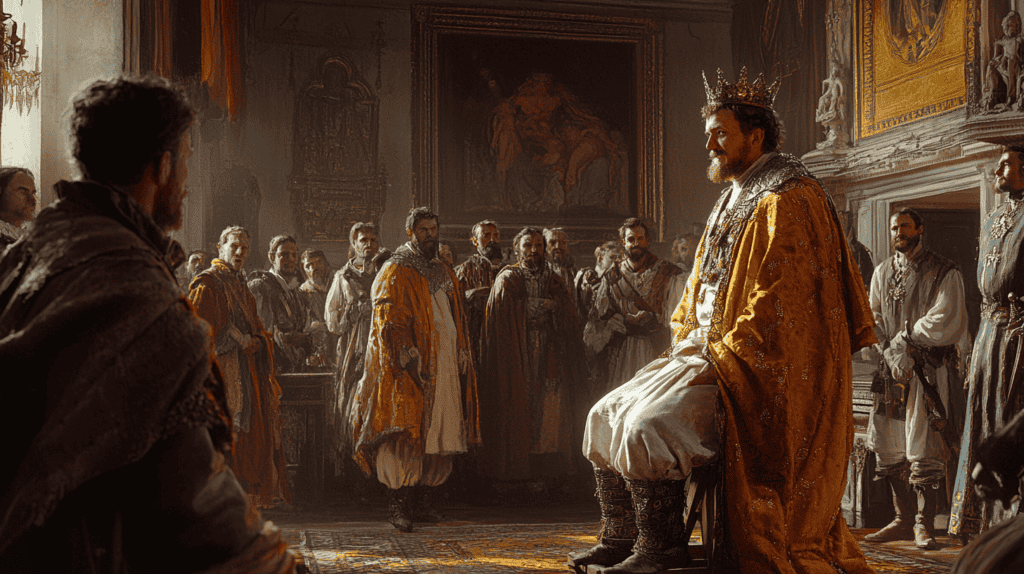

Following the death of Louis V, the assembly of Frankish magnates convened to elect a new king. This assembly, held in Senlis, would prove to be a turning point in French history. Archbishop Adalberon played a crucial role in swaying the nobles’ decision

In a stirring oration, Adalberon argued that the crown should be elective rather than hereditary. He also contended that Charles of Lorraine, the only legitimate Carolingian contender, was unfit to rule. This persuasive speech, combined with Hugh Capet’s political influence and military strength, tipped the scales in his favor.

The Coronation and Its Implications

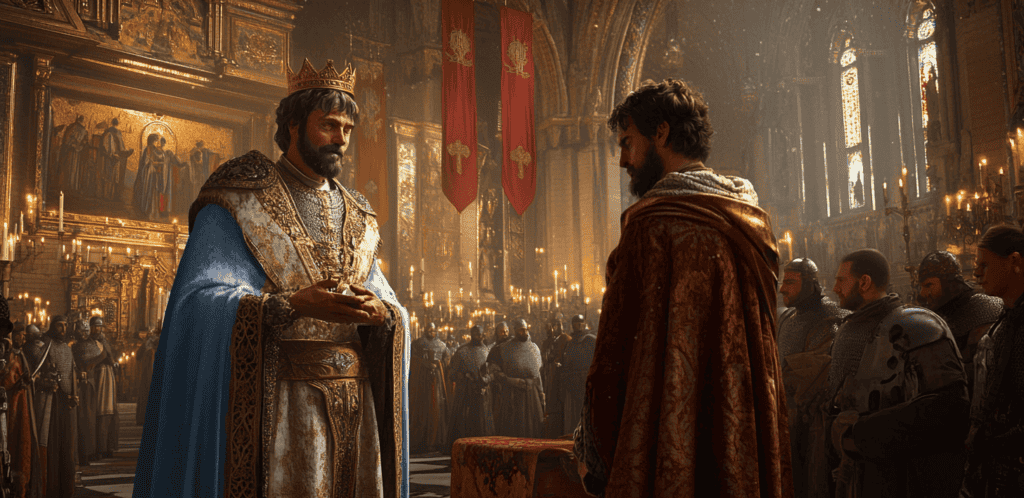

On July 3, 987, Hugh Capet was crowned King of the Franks in Noyon by Archbishop Adalberon. This event marked the official beginning of the Capetian dynasty, which would rule France for nearly nine centuries in various branches.

Hugh Capet’s coronation was carefully orchestrated to emphasize legitimacy and continuity with the past. He was anointed with the holy oil traditionally used for Frankish kings, including the legendary Clovis I. This ritual symbolically linked Hugh to the long line of Frankish rulers, despite his lack of Carolingian blood.

Nonetheless, some nobles saw him as a mere “Count of Paris,” and more than a few questioned his legitimacy. Once, when visiting a prominent noble, Hugh Capet was offered a seat that seemed all too familiar to him: a low wooden stool, commonly used by peasants. The slight was deliberate. His host wanted to send a clear message that he did not view Hugh as anything close to a monarch. Hugh, however, was quick on his feet. With a wry smile, he accepted the stool without complaint, sitting down as if it were a throne. He even thanked his host, remarking that kings should not be above their subjects. This earned him the grudging respect of some, who admired his resilience and humility.

Challenges and Consolidation of Power

Hugh Capet’s reign, which lasted from 987 to 996, was not without its challenges. The new king faced opposition from various quarters and had to work diligently to consolidate his power.

At the time of Hugh’s coronation, the royal domain was relatively small, centered primarily around Paris and Orléans. Much of what we now consider France was controlled by powerful nobles who often acted independently of the crown. Hugh had to navigate carefully to maintain his authority without alienating these regional powers.

One of Hugh Capet’s most significant achievements was securing the succession for his son, Robert. In December 987, just months after his own coronation, Hugh had Robert crowned as co-king in Orléans. This practice of crowning the heir during the father’s lifetime would become a Capetian tradition, contributing greatly to the dynasty’s stability and longevity.

The Capetian Legacy

Hugh Capet’s reign, though relatively short, laid the foundation for one of the most enduring dynasties in European history. The Capetian kings would rule France directly until 1328, and through cadet branches (the Valois and Bourbon dynasties) until the French Revolution in 1792.

Over the centuries, the Capetian monarchs gradually expanded their authority, centralizing power and creating a more unified French state. This process, which began under Hugh Capet, would reach its apex with absolutist monarchs like Louis XIV in the 17th century.

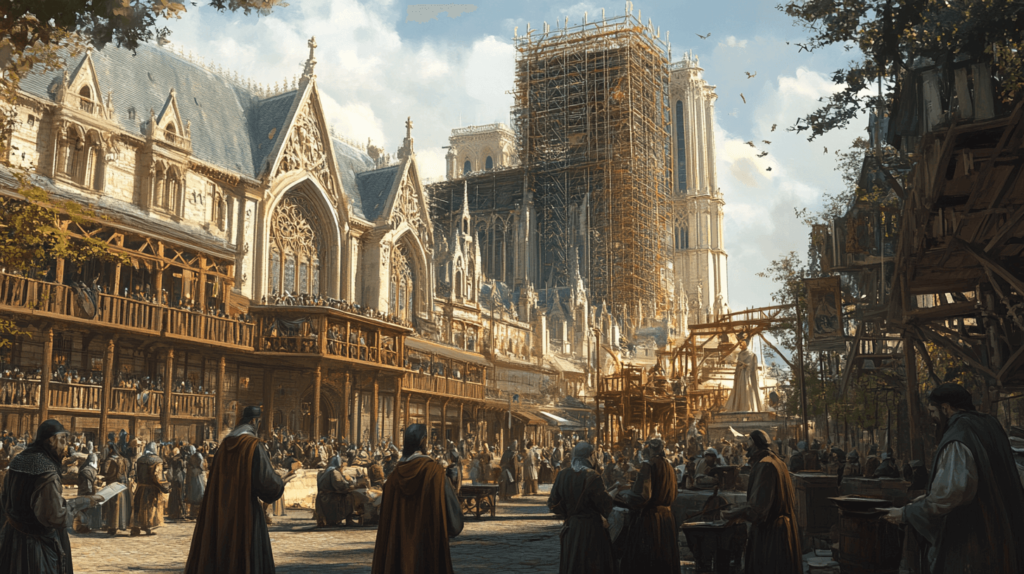

The establishment of the Capetian dynasty also had profound cultural implications. The dialect of the Île-de-France region, where the Capetian power base was located, gradually became the standard for the French language. This linguistic unification played a crucial role in forging a distinct French national identity. While the construction of great cathedrals, the founding of universities, and the flourishing of courtly culture all contributed to France’s growing prestige. Paris, in particular, emerged as a leading intellectual and artistic center as Europe entered the medieval period.

In the early years of Capetian rule, France was often overshadowed by the Holy Roman Empire and England. However, as the French monarchy consolidated its power, it began to assert itself more forcefully in European affairs. This would eventually lead to conflicts like the Hundred Years’ War with England and the Italian Wars against the Holy Roman Empire.

The gradual centralization of power under the Capetians contributed to the emergence of a distinct French national identity. This process, which took centuries to unfold, would eventually lead to the concept of the nation-state that dominates modern political thinking.

I love history, love reading these articles thank you!

Thanks Georgia – I enjoy researching the topics