The story of the Angles and their invasion of Britain is a fascinating chapter in the history of England, marking the transition from post-Roman Britain to Anglo-Saxon England. This tale of migration, conquest, and cultural transformation would shape the destiny of the British Isles for centuries to come.

Origins of the Angles

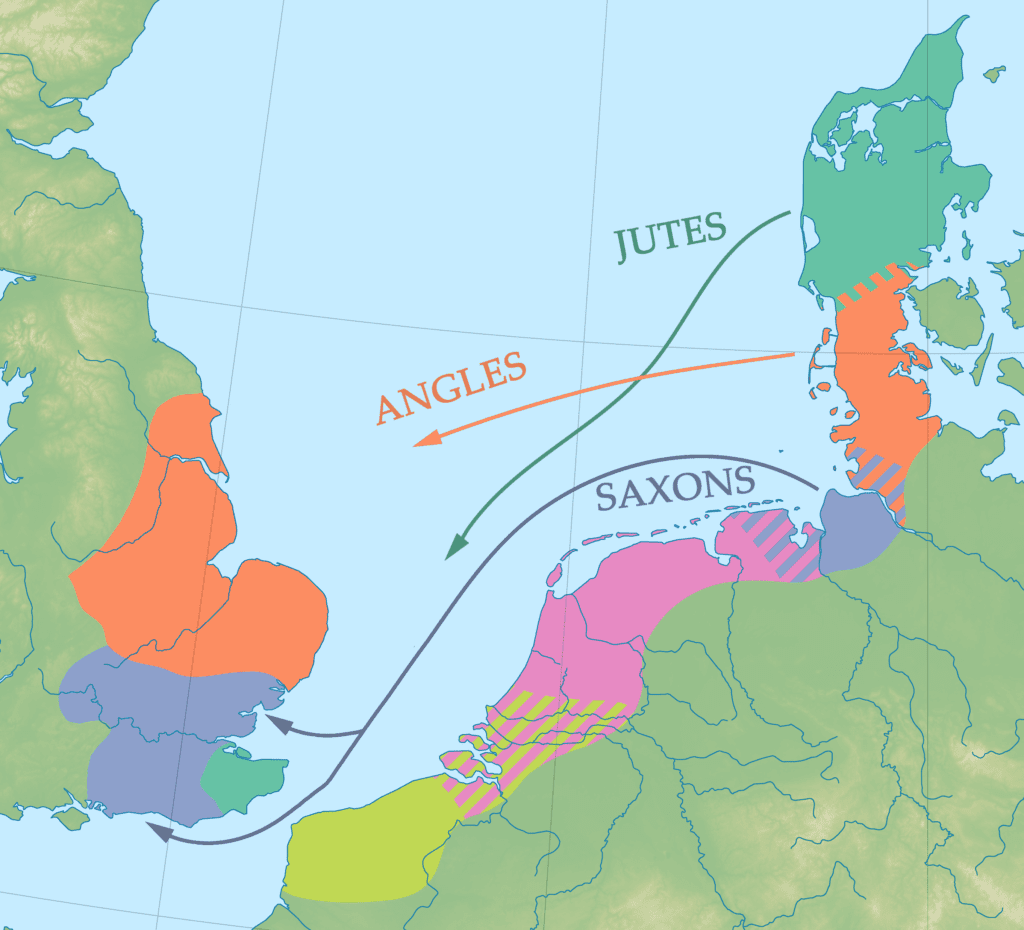

The Angles were a Germanic tribe originating from the Angeln peninsula in modern-day Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. Along with their close relatives, the Saxons and Jutes, the Angles were part of the broader group of North Sea Germanic peoples.

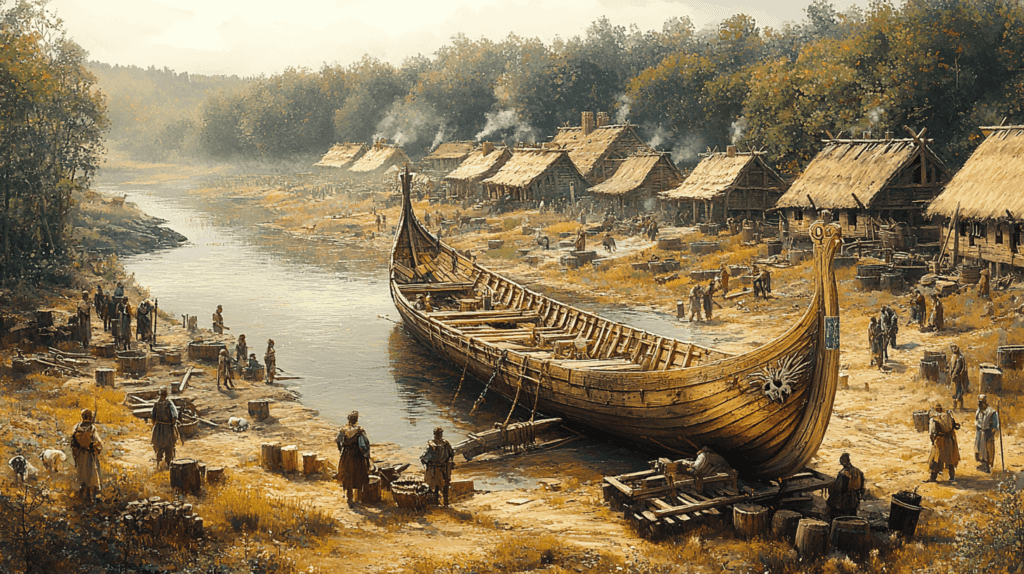

Archaeological evidence suggests that the Angles had a well-developed society in their homeland, with a mixed economy based on agriculture, animal husbandry, and trade. They were skilled metalworkers and boat builders, traits that would serve them well in their future adventures across the North Sea.

The Invitation and Initial Migration

The traditional narrative of the Anglo-Saxon invasion, as recounted by the 8th-century monk Bede in his “Ecclesiastical History of the English People,” begins with an invitation. According to Bede, in the mid-5th century, a British king named Vortigern invited Germanic mercenaries to help defend Britain against raids by the Picts and Scots.

While this account is now viewed with some skepticism by historians, it does reflect a broader historical reality. The withdrawal of Roman legions from Britain in 410 AD had left a power vacuum, and various local rulers sought to fill it. Some may indeed have recruited Germanic warriors to bolster their forces.

The initial Angle settlements in Britain were likely small-scale affairs, with bands of warriors establishing footholds along the eastern coast. These early settlers may have acted as mercenaries or independent raiders, taking advantage of the weakened state of post-Roman Britain.

The Great Migration

The trickle of Angle settlers soon became a flood. By the late 5th and early 6th centuries, larger groups of Angles were crossing the North Sea, bringing with them not just warriors, but entire families and communities. This was not merely a military invasion, but a mass migration that would fundamentally alter the demographic and cultural landscape of Britain.

The reasons for this large-scale movement are complex and debated. Climate change may have played a role, with rising sea levels in the Angles’ homeland making agriculture more difficult. Population pressure and political instability in continental Europe may also have been factors. Whatever the reasons, the result was a significant influx of Angle settlers into Britain.

The newcomers established themselves primarily in the eastern and northern parts of England. Archaeological evidence, including distinctive styles of pottery and burial practices, allows us to trace the spread of Angle settlement across the country.

Conflict and Conquest

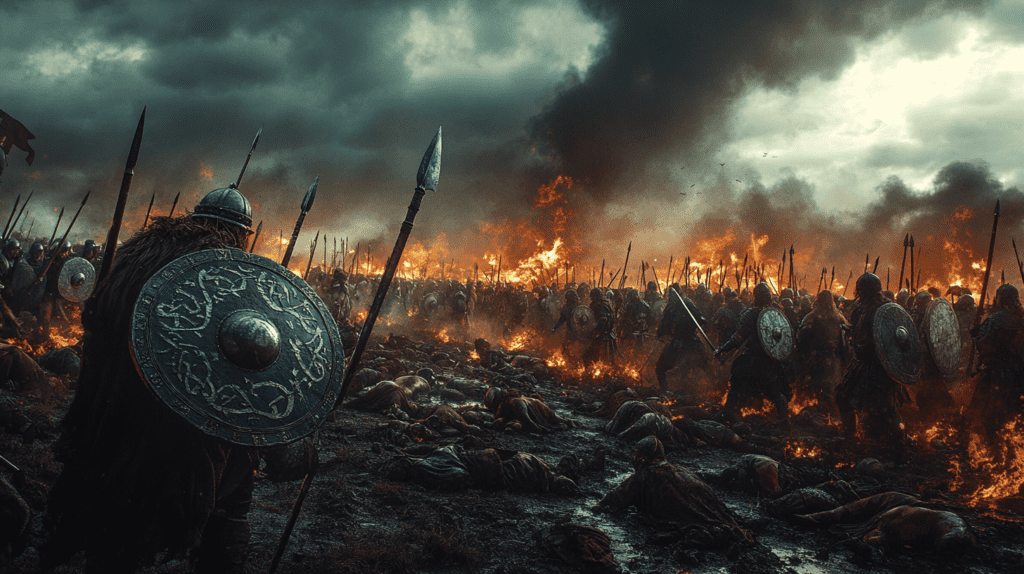

The arrival of the Angles and other Germanic peoples was not always peaceful. While some British rulers may have initially welcomed them as allies or mercenaries, conflicts soon erupted. The incoming Angles, with their superior military organization and weaponry, often had the upper hand in these struggles.

One of the most significant battles of this period was the Battle of Badon, believed to have taken place around 500 AD. According to later British sources, this battle saw a great victory for the Britons against the invading Anglo-Saxons, temporarily halting their advance. Some scholars associate this battle with the legendary King Arthur, though there is no contemporary evidence for his existence.

Despite occasional setbacks, the Angles and their Germanic allies gradually extended their control over much of lowland Britain. The native Britons were pushed westward into Wales and Cornwall, or assimilated into the new Anglo-Saxon culture.

The Establishment of Angle Kingdoms

As the Angles consolidated their hold on their new territories, they began to establish more organized political entities. By the 6th century, several distinct Angle kingdoms had emerged:

East Anglia

One of the earliest and most prominent Angle kingdoms was East Anglia, encompassing modern-day Norfolk and Suffolk. The name “East Anglia” itself means “land of the Eastern Angles.” The kingdom was founded by the Wuffingas dynasty, named after their semi-legendary ancestor Wuffa.

East Anglia quickly became a center of power and culture in Anglo-Saxon England. The famous Sutton Hoo ship burial, discovered in 1939, is believed to be the grave of an East Anglian king, possibly Rædwald, who ruled in the early 7th century. The spectacular treasures found at Sutton Hoo, including a magnificent helmet and intricate gold jewelry, testify to the wealth and sophistication of the East Anglian royal court.

Mercia

The kingdom of Mercia, centered in the English Midlands, emerged as one of the most powerful Angle realms. While its early history is obscure, by the 7th century, Mercia was a formidable force under kings like Penda and Offa.

Penda, who ruled from about 626 to 655, was a fierce pagan who resisted the spread of Christianity and led Mercia to dominance over its neighbors. Offa, ruling from 757 to 796, brought Mercia to its zenith, exerting control over much of southern England and even claiming the title “King of the English.”

Offa is perhaps best known for the construction of Offa’s Dyke, a massive earthwork still running along the border between England and Wales. This monumental project, stretching for over 150 miles, demonstrates the power and organizational capacity of the Mercian state.

Northumbria

In the north, the kingdom of Northumbria was formed from the union of two earlier Angle realms: Bernicia and Deira. Northumbria stretched from the Humber estuary to the Firth of Forth, encompassing much of northern England and southern Scotland.

Under kings like Edwin (616-633) and Oswald (634-642), Northumbria became a major power in Britain. It was also a center of learning and culture, particularly after the adoption of Christianity. The monastery of Lindisfarne, founded in 635, became a beacon of scholarship, producing illuminated manuscripts like the famous Lindisfarne Gospels.

Other Angle Kingdoms

Several smaller Angle kingdoms also emerged, including Lindsey in Lincolnshire and the Hwicce in the Severn Valley. While these realms were often overshadowed by their larger neighbors, they played important roles in the complex political landscape of Anglo-Saxon England.

The Angle Impact on Britain

The Angle invasion and settlement had a profound and lasting impact on Britain. Perhaps the most significant change was linguistic. The Old English language, which evolved from the dialects spoken by the Angles and other Germanic settlers, gradually replaced the Celtic and Latin languages previously spoken in lowland Britain.

This linguistic shift was accompanied by cultural changes. The Angles brought with them their own religious beliefs, social structures, and artistic traditions. While some elements of Romano-British culture survived, particularly in urban areas, much of lowland Britain was transformed into a distinctly Anglo-Saxon society.

The impact can be seen in place names across England. Many towns and villages bear names of Angle origin, often ending in suffixes like “-ham” (meaning homestead), “-ton” (town), or “-ing” (people of). For example, England’s second biggest city Birmingham literally means “homestead of Beorma’s people.”

Christianity and the Angles

The conversion of the Angle kingdoms to Christianity was a gradual process that had far-reaching consequences. The first major push came in 597, when Pope Gregory I sent a mission led by Augustine to convert the Anglo-Saxons. While Augustine’s mission focused initially on the kingdom of Kent, its influence soon spread.

In Northumbria, King Edwin’s conversion in 627 marked a turning point. Although there was a brief pagan revival under his successor Oswald, Christianity eventually took firm root. The Northumbrian church, influenced by both Roman and Celtic traditions, became a major center of learning and culture.

Mercia, under Penda, remained a bastion of paganism until the mid-7th century. However, Penda’s son Peada accepted Christianity, and by the end of the century, all the major Anglo-Saxon kingdoms had officially converted.

The adoption of Christianity brought the Angle kingdoms into closer contact with continental Europe and the broader Christian world. It also provided a unifying force in a politically fragmented landscape and played a crucial role in the development of English literature and art.

Viking Invasions and the Decline of the Angle Kingdoms

The relative stability of the Angle kingdoms was shattered in the late 8th century with the onset of Viking raids. In 793, the monastery of Lindisfarne was sacked, marking the beginning of a new era of conflict and upheaval.

The Vikings, primarily from Denmark and Norway, initially came as raiders but soon began to establish permanent settlements. The kingdom of Northumbria was particularly hard-hit, with York (Jorvik) becoming the center of a Viking kingdom in 866.

East Anglia fell to the Vikings in 869, with its king, Edmund, being killed in battle. His martyrdom would later make him a popular saint in medieval England. Mercia, too, was overrun, with much of its territory becoming part of the Danelaw, the area of England under Viking control.

The Rise of Wessex and the Birth of England

As the old Angle kingdoms crumbled under Viking assault, the West Saxon kingdom of Wessex emerged as the leading power in England. Under King Alfred the Great (871-899) and his successors, Wessex not only resisted Viking conquest but began to reconquer the lost territories.

Alfred’s grandson, Æthelstan (924-939), was the first ruler to effectively unite all of England under a single crown. While he and his successors styled themselves as “King of the English,” their realm was essentially an expanded Wessex that had absorbed the former Angle kingdoms.

This process of unification marked the end of the distinct Angle kingdoms as political entities. However, the Angle heritage remained an important part of English identity. The very name “England” derives from “Angle-land,” the land of the Angles.