The Coming of the Saxons

Traditional accounts, such as those provided by the 8th-century monk Bede, paint a dramatic picture of the Saxon arrival. According to Bede, the first significant influx occurred in 449 AD, when a British king (possibly named Vortigern) invited Germanic mercenaries to help defend against the Picts and Scots.

However, modern historians and archaeologists paint a more complex picture. Evidence suggests that Germanic peoples had been settling in Britain since at least the 3rd century AD, often as Roman auxiliaries. The “invasion” was likely a gradual process of migration and settlement rather than a single, dramatic event.

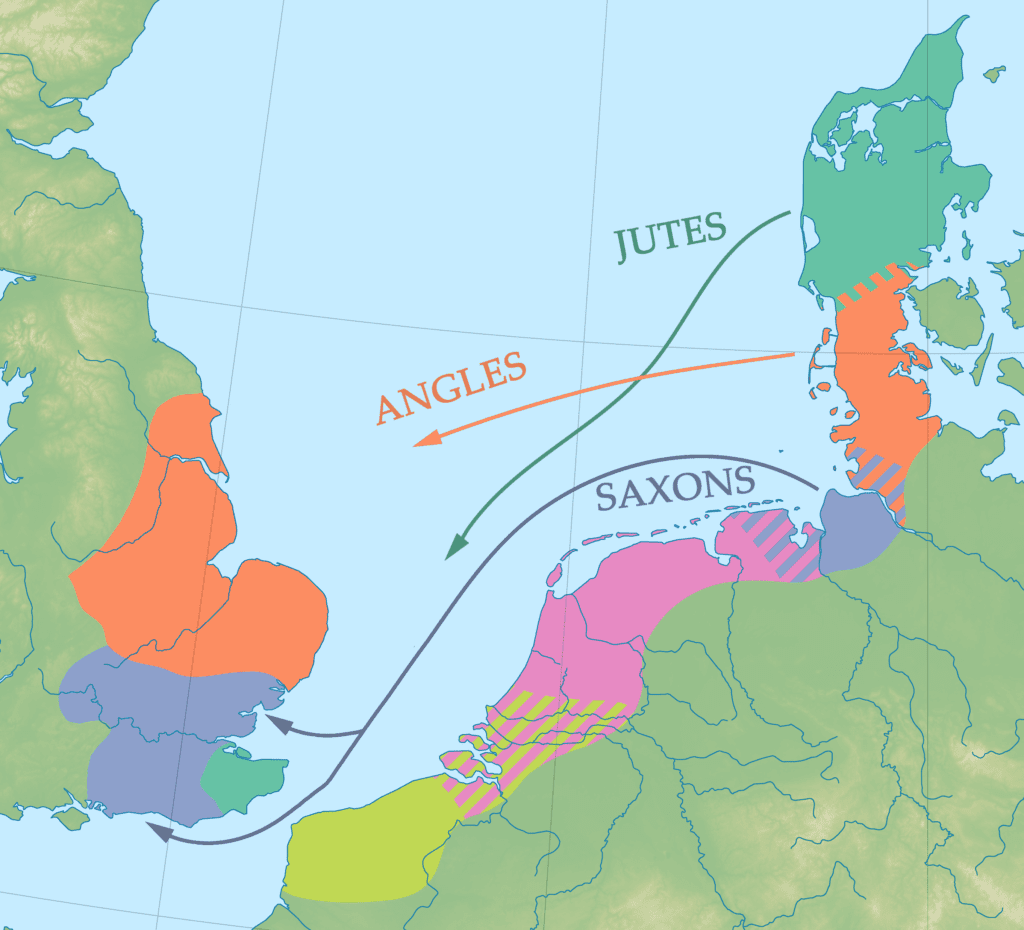

The Saxons, originating from what is now northern Germany and the Netherlands, were one of the main groups of these Germanic settlers. They were joined by the Angles from southern Denmark and the Jutes from Jutland. Together, these groups would come to be known as the Anglo-Saxons, though the term “Saxon” was often used more broadly to refer to all these Germanic settlers.

The Early Saxon Settlements

The Saxon settlers initially established themselves along the eastern and southern coasts of England. Archaeological evidence, including distinctive styles of pottery, jewelry, and burial practices, allows us to trace their spread across the country.

One of the earliest Saxon settlements was in Sussex (meaning “South Saxons”), established around 477 AD. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a Saxon leader named Ælle and his three sons landed on the south coast and gradually conquered the area, defeating the local Britons.

In 495 AD, another group of Saxons led by Cerdic and Cynric landed in what would become Wessex (West Saxons). They faced fierce resistance from the Britons but gradually expanded their territory. In 519 AD, they decisively defeated the Britons and established the Kingdom of Wessex, which would later become the most powerful of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

To the east, the Saxons established the Kingdom of Essex (East Saxons) around 527 AD, although the exact date and circumstances of its founding are less clear than those of Sussex and Wessex.

Conflict and Conquest

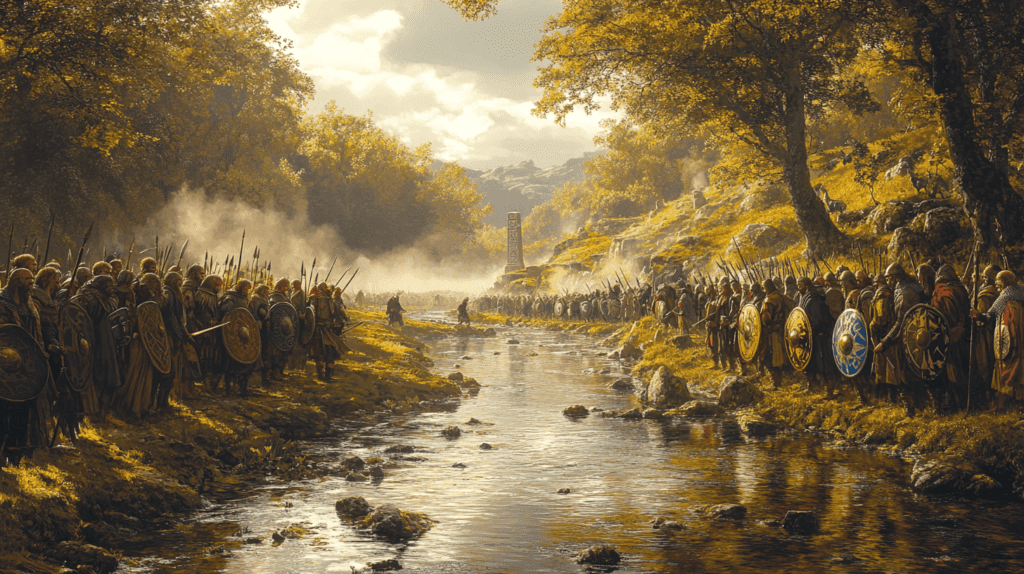

The arrival of the Saxons was not always peaceful. While some may have come as invited mercenaries or settlers, others came as invaders and conquerors. The native Britons resisted fiercely in many areas.

A significant battle in this period was the Battle of Mount Badon, believed to have taken place around 500 AD. According to later British sources, this battle saw a great victory for the Britons against the invading Saxons, temporarily halting their advance. Some scholars associate this battle with the legendary King Arthur, though there is no contemporary evidence for his involvement.

Despite this resistance, the Saxons gradually extended their control over much of lowland Britain. The native Britons were pushed westward into Wales and Cornwall, or assimilated into the new Anglo-Saxon culture. As the Saxons consolidated their hold on their new territories, they began to establish more organized political entities.

The Heptarchy: The Seven Kingdoms

By the 7th century, the political landscape of Anglo-Saxon England had coalesced into seven major kingdoms, often referred to as the Heptarchy. While not all of these were Saxon kingdoms, they were all part of the broader Anglo-Saxon cultural sphere:

- Wessex (Saxon)

- Essex (Saxon)

- Sussex (Saxon)

- Kent (Jutish)

- East Anglia (Anglian)

- Mercia (Anglian)

- Northumbria (Anglian)

Let’s explore the Saxon kingdoms in more detail:

Wessex: The Kingdom of the West Saxons

Wessex, founded by Cerdic in 519 AD, would eventually rise to dominate all of England. Its early years were marked by constant warfare with the native Britons and neighboring Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

Key moments in the early history of Wessex include:

- 552 AD: Capture of Old Sarum, expanding Wessex into western Hampshire

- 556 AD: Victory at Beranburh, allowing further westward expansion

- 577 AD: Victory at the Battle of Deorham, leading to the capture of the important Roman cities of Gloucester, Cirencester, and Bath

Under kings like Cædwalla (685-688) and Ine (688-726), Wessex began to emerge as a major power. Ine is particularly notable for issuing one of the earliest known Saxon law codes.

Essex: The Kingdom of the East Saxons

Essex was founded around 527 AD, possibly by King Æscwine. The kingdom included the modern county of Essex as well as parts of Hertfordshire and Middlesex. Essex was often overshadowed by its more powerful neighbors, particularly Kent and Mercia. It was one of the last Anglo-Saxon kingdoms to convert to Christianity, with King Sæberht accepting baptism around 604 AD under the influence of his uncle, King Æthelberht of Kent.

Sussex: The Kingdom of the South Saxons

Sussex, founded by Ælle around 477 AD, was one of the smallest and least powerful of the Saxon kingdoms. It was often dominated by its neighbors, particularly Wessex and Mercia. Despite its small size, Sussex played an important role in the early spread of Christianity among the Saxons. In 681 AD, St. Wilfrid arrived in Sussex and began converting the South Saxons to Christianity.

Culture and Society in Saxon England

The Saxon period saw significant changes in the culture and society of Britain. The Old English language, which evolved from the dialects spoken by the Saxons and other Germanic settlers, gradually replaced the Celtic and Latin languages previously spoken in lowland Britain.

Social structure in Saxon England was hierarchical. At the top were the kings and their immediate families. Below them were the ealdormen (nobles who governed shires on behalf of the king) and thegns (lesser nobles who served as the king’s warriors). The majority of the population were ceorls (free peasants) and thralls (slaves).

Saxon culture placed great value on loyalty, courage, and generosity. These ideals are reflected in Old English poetry like “Beowulf,” which tells the story of a heroic warrior who battles monsters and dragons.

The Saxons were skilled craftsmen, producing intricate jewelry, weapons, and other artifacts. They were also farmers, introducing new agricultural techniques and crops to Britain.

The Conversion to Christianity

The Saxons initially brought their pagan Germanic beliefs with them to Britain. They worshipped gods like Woden, Thunor, and Frig (from whom we get the names Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday). However, the conversion to Christianity would prove to be one of the most significant cultural shifts of the Saxon period.

The process began in earnest in 597 AD when Pope Gregory I sent a mission led by Augustine to convert the Anglo-Saxons. Augustine’s mission focused initially on Kent, where he found a receptive audience in King Æthelberht, whose wife was already a Christian.

From Kent, Christianity spread to other Saxon kingdoms. In Essex, King Sæberht was baptized around 604 AD. Wessex was slower to convert, with paganism persisting until the mid-7th century when King Cynegils was baptized in 635 AD.

The adoption of Christianity brought the Saxon kingdoms into closer contact with continental Europe and the broader Christian world. It also provided a unifying force in a politically fragmented landscape and played a crucial role in the development of English literature and art.

The Viking Invasions and the Rise of Wessex

The relative stability of the Saxon kingdoms was shattered in the late 8th century with the onset of Viking raids. In 793, the monastery of Lindisfarne in Northumbria was sacked, marking the beginning of a new era of conflict and upheaval.

The Vikings, primarily from Denmark and Norway, initially came as raiders but soon began to establish permanent settlements. Many of the Saxon kingdoms fell to the Vikings. Essex was conquered by the Vikings in 870 AD, while Sussex was absorbed into Wessex around the same time as a defensive measure against Viking attacks.

As the old Saxon kingdoms crumbled under Viking assault, Wessex emerged as the leading power in England. Under King Alfred the Great (871-899) and his successors, Wessex not only resisted Viking conquest but began to reconquer the lost territories.

Alfred’s achievements were remarkable:

- He defeated the Vikings at the Battle of Edington in 878 and converted their leader Guthrum to Christianity.

- He established a boundary between Saxon and Viking territories – the Danelaw.

- He strengthened Wessex’s defenses by creating a network of fortified towns (burhs) and reorganizing the army.

- He built ships to counter Viking sea attacks, laying the foundation for the English navy.

- He promoted learning and literacy, commissioning translations of important works into Old English and initiating the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

The Birth of England

Alfred’s successors continued his work of reconquest and unification. His son Edward the Elder and grandson Æthelstan extended West Saxon control over the Danelaw. Æthelstan (924-939) was the first ruler to effectively unite all of England under a single crown.

While Æthelstan and his successors styled themselves as “King of the English,” their realm was essentially an expanded Wessex that had absorbed the former Saxon and Anglian kingdoms.

The Saxon period in England came to an end with the Norman Conquest of 1066. When the childless King Edward the Confessor died in January 1066, it triggered a succession crisis. Harold Godwinson, the last Saxon king of England, was crowned, but faced challenges from Harald Hardrada of Norway and William, Duke of Normandy.

Harold defeated Harald at the Battle of Stamford Bridge in September, but was then defeated and killed by William at the Battle of Hastings on October 14, 1066. William the Conqueror, as he became known, was crowned King of England on Christmas Day 1066, marking the end of Saxon rule and the beginning of Norman England.

Legacy of the Saxons

The legacy of the Saxons in Britain is profound and enduring. The English language, one of the world’s most widely spoken languages, evolved from their dialects. The political geography of England, with its counties and shires, has its roots in Saxon administrative divisions.

Saxon legal traditions, including the concept of common law and trial by jury, formed the basis of the English legal system. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, initiated by Alfred the Great, began a tradition of historical writing in English that continues to this day.

Even after the Norman Conquest, many aspects of Saxon culture persisted. The Normans, themselves descendants of Vikings who had settled in France, gradually blended with the Saxon population, creating the unique culture of medieval England.