Matilda of Tuscany, also known as La Gran Contessa (The Great Countess), was one of the most remarkable figures of the Italian Middle Ages. Her military exploits, political acumen, and unwavering support for church reform made her a legend in her time and a rare example of a medieval woman who commanded armies and shaped history.

Early Life and Rise to Power

Born in 1046, Matilda was the youngest child of Boniface III, Margrave of Tuscany, and Beatrice of Lorraine. Her father was one of the most powerful vassals of the Holy Roman Emperor, while her mother came from an influential noble family closely connected to the imperial court. Matilda’s early education was exceptional for a woman of her time; she was fluent in multiple languages, well-versed in theology, and trained in military strategy and combat skills—an unusual preparation for her future role as a military leader.

Following the death of her father in 1052 and her brother’s mysterious death shortly thereafter, Matilda became the sole heir to one of the largest territorial lordships in Italy. Her mother acted as regent until Matilda came of age. The political climate during this period was fraught with tension as the Canossa family became deeply involved in papal politics, particularly during disputed elections that eventually saw Matilda’s uncle become Pope Stephen IX.

The Investiture Controversy and Early Military Campaigns

Matilda’s military career began during one of the most turbulent periods in medieval European history: the Investiture Controversy. This conflict centered on whether secular rulers or the pope held the authority to appoint bishops and invest them with temporal power. Matilda aligned herself firmly with Pope Gregory VII, becoming his staunchest ally against Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV.

In 1076, Matilda played a crucial role in protecting Pope Gregory VII during his perilous journey north to meet rebellious German princes at Trebur. She used her control over key Apennine passes, which had been heavily fortified, to shield the pope from capture by excommunicated Lombard bishops allied with Henry IV, himself now excomunicated. This marked her first significant military endeavor.

The Walk to Canossa

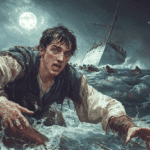

Henry’s excommunication from the Church had undermined his legitimacy as Holy Roman Emperor, as many of his vassals began to question their loyalty. Faced with rebellion at home and political isolation, Henry took a desperate step. He resolved to seek absolution from Pope Gregory VII in person. This decision led him on a grueling journey across the Alps in the dead of winter—a trek that underscored both his determination and vulnerability. The winter of 1076-1077 was particularly harsh, with blizzards raging across the mountain passes. Accompanied by a small retinue, Henry braved these treacherous conditions to reach Canossa Castle in northern Italy, where Pope Gregory was staying as a guest of Matilda.

When Henry arrived at Canossa in January 1077, he found himself barred from immediate entry. According to contemporary accounts, he was made to wait outside the castle gates for three days and nights, clad in penitential garb—a woolen tunic—while snowstorms swirled around him. This act of penance was both a personal humiliation and a public spectacle. It demonstrated the immense power wielded by the Church, as even an emperor had to humble himself before the pope.

Finally, on January 28, Gregory relented and admitted Henry into the castle. The emperor reportedly knelt before the pope and begged for forgiveness. Gregory absolved him after extracting promises of obedience. Yet this reconciliation was fraught with ambiguity. While it restored Henry’s standing within Christendom temporarily, it did not resolve their underlying conflict over investiture rights.

The conflict escalated again in 1080 when Henry IV declared an antipope, Clement III, and marched into Italy to assert his authority. Matilda’s forces suffered initial defeats, including a significant loss near Volta Mantovana. Despite these setbacks, she refused to surrender and maintained control over critical mountain passes, forcing Henry to take longer routes to besiege Rome.

The Battle of Sorbara (1084): A Turning Point

One of Matilda’s most celebrated victories occurred on July 2, 1084, at Sorbara. After years of defensive warfare against Henry IV, she launched a surprise dawn raid on an imperial camp near Modena. Her forces decimated Henry’s troops, capturing knights and horses while suffering minimal losses themselves. This victory reinvigorated papal supporters at a time when Henry seemed poised for triumph.

Following Sorbara, Matilda shifted from defensive campaigns to offensive operations. She became a rallying point for church reformers and provided military support to successive popes after Gregory VII’s death in 1085. Her ability to maintain alliances and fortify her territories allowed her to resist imperial advances effectively.

The Siege of Canossa (1092): Matilda’s Defining Moment

In 1090, Henry IV launched another campaign against Matilda, capturing key cities such as Mantua and Verona through military force and political bribery. By 1092, he turned his attention to Canossa Castle, Matilda’s ancestral stronghold and the site of Henry’s earlier humiliation during the Walk to Canossa in 1077. Despite losing much of her territory north of the Po River, Matilda refused peace terms that would have required her to recognize Clement III as pope.

As Henry laid siege to Canossa, Matilda withdrew with her forces to an outlying fortress. When Henry’s troops exhausted themselves against Canossa’s defenses, she launched a counterattack that turned his siege into a rout. Her forces harassed his retreating army across the Po Valley, delivering a crushing blow that marked the end of Henry’s influence in Italy.

Henry IV’s retreat from Canossa not only signaled his diminishing power but also underscored Matilda’s ability to rally support against imperial forces. Her coalition effectively blocked Clement III, Henry’s appointed anti-pope, from returning to Rome, leaving Urban II firmly in control of the Holy See.

Later Campaigns and Political Maneuvering

After Henry IV’s defeat at Canossa, Matilda continued to consolidate her power and support church reform. She played a key role in restoring Pope Urban II to Rome after years of exile and supported his efforts to launch the First Crusade. Between 1101 and 1114, she led or directed campaigns against rebellious cities such as Ferrara, Parma, Prato, and Mantua.

Matilda also used marriage as a political tool. In 1089, she married Welf V of Bavaria to strengthen alliances against Henry IV. However, their union was short-lived due to personal incompatibility; they separated in 1095 without producing heirs. Despite this setback, Matilda maintained her influence through strategic alliances with local leaders and towns.

Legacy as a Military Leader

Matilda’s military career spanned over four decades—a remarkable achievement for any medieval ruler but especially for a woman in a male-dominated society. She commanded armies in long-distance expeditions, directed sieges and ambushes, built fortifications, and maintained an effective intelligence network. Her ability to inspire loyalty among her followers ensured that she could field troops even during times of political isolation.

Her final military action occurred in 1114 when she suppressed a revolt in Mantua less than a year before her death at age 69. By then, she had not only defended her territories but also shaped the course of European history by ensuring the survival of papal authority during one of its most critical periods.

Legacy

Matilda of Tuscany remains an enduring symbol of resilience and leadership. Her military exploits demonstrated exceptional strategic acumen and courage under pressure. As both a warrior and a patron of church reform, she left an indelible mark on medieval Europe. Today, she is remembered not only as La Gran Contessa but also as one of history’s most formidable female leaders.