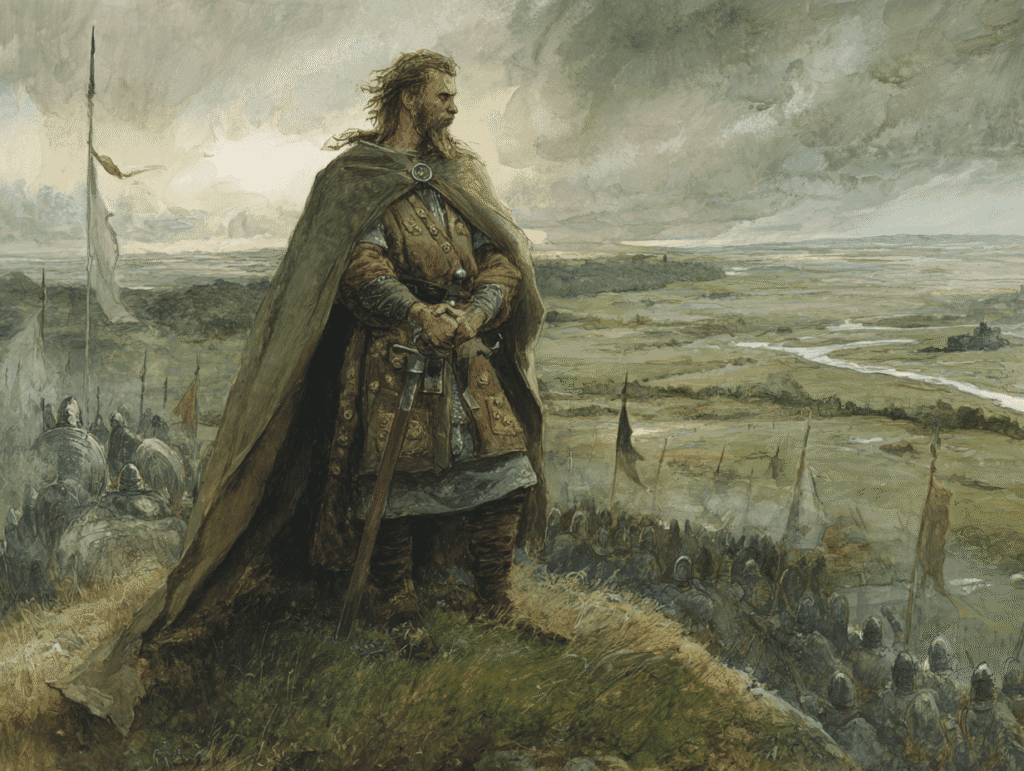

Conn of the Hundred Battles strides through early Irish tradition as both a warlord and a world‑maker, the man whose sword supposedly carved Ireland into “Conn’s Half” and “Mug’s Half” and whose descendants would claim vast swathes of the island’s kingship as their birthright.

A birth under bad omens

The poets said that on the night Conn was born, Ireland rearranged itself to make room for him. At Tara, the ritual heart of the island, watchers peered into the dark and saw a marvel that no annalist could quite ignore: five great roads, straight as spear‑shafts, suddenly stood revealed, converging like arteries into the royal hill, as if the land itself had drawn its lines towards the child who would one day claim to rule it.

Those roads were later named the five royal roads of Tara, and the chroniclers, with their love of symbolism, insisted they had never been seen before that night. To them, it meant that every province, every kingdom, every cattle‑rich plain would be drawn inexorably toward Conn’s kingship, whether in allegiance or in war; the boy was born, they said, under an omen of gathering fate.

He was the son of Fedlimid Rechtmar (“the Lawgiver”), himself remembered as a High King, which gave Conn an impeccable pedigree in later genealogies. In those lists, he stands as forefather of the Connachta and Uí Néill dynasties of the north, a name retroactively placed at the root of some of the most powerful medieval families in Ireland; yet already the sources hint that “Conn” might once have been something more or less than a man – perhaps an ancestral figure, perhaps even the worn‑down echo of an earlier pagan divinity of sovereignty.

The roaring stone at Tara

Conn’s path to the “kingship of Tara” is told not simply in dry succession lists but in stories where the land tests him. At Tara stood the Lia Fáil, the Stone of Destiny: a pillar said to roar when the rightful king placed his feet upon it. Long before Conn’s time, the warrior Cú Chulainn, furious when the stone refused to acknowledge another, had split it with his sword, leaving it mute. Then Conn came to Tara.

The tale says that when he stood on the Lia Fáil the stone gave voice again, bellowing across the hill as if the bedrock itself recognized him. One tradition even has the stone cry out the number of years Conn and his line would rule, a thunderous prophecy of his dynasty’s long tenure over Leth Cuinn, “Conn’s Half” of Ireland.

Yet Conn did not step into a vacant throne. In different strands of the tradition, the man who held power before him was either Cathair Mór, the great ancestor of Leinster’s kings, or Dáire Doimthech, another shadowy southern ruler. One account has Conn kill Cathair Mór in battle at Mag Ága near Tailtiu (Teltown in modern Meath), slicing down his own father‑in‑law to claim the kingship that Tara, and the Lia Fáil, had promised him. The story is blunt in its message: sovereignty in this age comes not by gentle inheritance but by force, even against a rival who shares your table and your blood.

“Of the Hundred Battles”

The epithet “Cétchathach” – “of the Hundred Battles” – is not subtle. Medieval writers understood kingship as a craft of war as much as of law, and Conn’s later reputation as an ideal king is built on the notion that he went to war again and again to defend and shape his realm.

The annalistic tradition credits him with an almost exhausting list of conflicts, especially against Munster and Leinster. He fights the Attacotti; he curbs Leinster’s ambitions when they balk at the cattle‑tribute (bóruma) first extorted, so tradition said, by his grandfather Tuathal Techtmar; and above all he wages a long and bitter struggle against Munster’s champion, Mug Nuadat (or his son, Éogan Mór, depending on the version).

By the time the legends stabilize, the number “hundred” does not need to be taken literally. It is a statement: this is a king whose reign is defined by battle after battle, a man whose very name becomes shorthand for militant, expanding kingship from Tara’s hill out into every corner of the island.

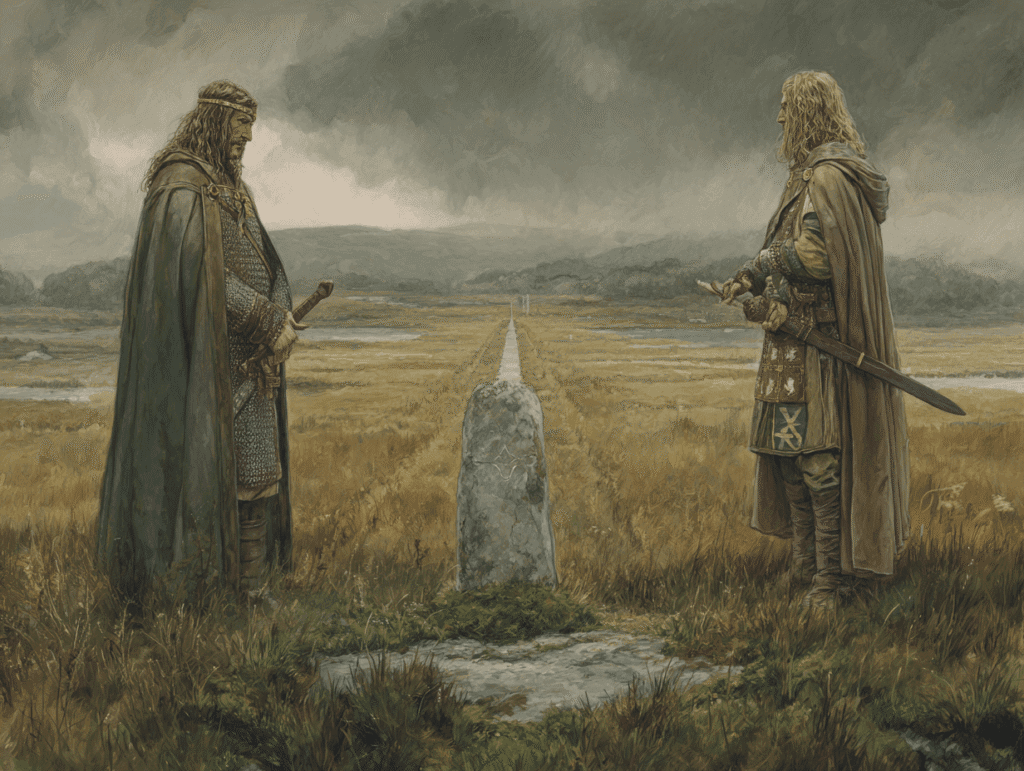

Mug Nuadat and the cutting of Ireland in two

No episode in Conn’s life is more dramatic than his rivalry with the Munster ruler Mug Nuadat. The pair are cast almost as opposites: Conn, the northern High King; Mug Nuadat, the southern challenger whose very name becomes attached to the “Half of Mug,” Leth Moga, as Conn’s does to Leth Cuinn.

The story runs like this. Mug Nuadat’s father, Mug Neit, begins the war by marching against Conn but is defeated and killed after two battles in what is now County Offaly. Mug Nuadat retreats through Munster, fighting a grim rearguard and finally slipping away by sea to Beare Island off the south‑west coast, and then, in a striking flourish, to Spain.

There, exile sharpens his ambition. Mug Nuadat marries the daughter of the king of Spain and returns nine years later with a new army, landing near Bantry Bay. Conaire and Mac Niad, kings of Munster under Conn’s overlordship, bend the knee to the returning exile; with Leinster and Ulster’s support, Mug Nuadat marches north into the central plain of Mag nAi and forces Conn to the bargaining table.

The compromise they strike will echo in Irish political geography for centuries: Ireland is divided in two along an imaginary line running from Galway on the west coast to Dublin on the east.

- North of that line is Leth Cuinn – Conn’s Half.

- South of it is Leth Moga – Mug’s Half.

On paper this is a peace treaty; in practice it is ideological cartography. Later writers use it to explain and legitimize the dominance of Conn’s supposed descendants in the north and west, setting them against the southern Éoganachta and others who could be linked, by story, to Mug Nuadat.

In some versions, notably Geoffrey Keating’s 17th‑century account, the war is messier still. Keating has Mug Nuadat raise a Leinster army, expel three kings from Munster, and then repeatedly beat back Conn’s attempts to restore them, forcing the High King, not once but many time, to accept the division of the island. This Conn is still formidable, but he is also constrained, out-manoeuvred, his power bounded by the ambitions of southern kings.

The night battle at Mag Leana

The peace between Leth Cuinn and Leth Moga lasts, in the legend, for fifteen years. Then Mug Nuadat, unsatisfied with half a kingdom, breaks the treaty. With the kings of Ulster and Leinster at his back, he marches north again, this time to Mag Leana, near modern Tullamore in County Offaly.

Conn, forced backwards, retreats into Connacht to gather his strength. In the interval, Mug Nuadat occupies Meath and Tara’s hinterland; the southern king’s shadow falls over the ritual heart of Conn’s kingship. But Conn is not finished.

Conn drives into Meath, retaking the territory from Ulster’s king, and then turns south toward Mag Leana. The decisive battle comes not in a blazing midday clash but in a carefully prepared night assault: Conn’s forces fall on Mug Nuadat’s camp under cover of darkness, catching his enemies sleeping or half‑armed. Mug Nuadat’s army is destroyed, and Mug himself dies in the chaos, cut down in the night on that Offaly plain.

This victory restores Conn’s authority over all Ireland, returning Leth Moga into Leth Cuinn by right of conquest. Later tradition points to mounds on the landscape, still shown in the 19th century as the graves of the southern king and his comrades, as if the earth were still quietly holding the memory of Conn’s greatest triumph.

Family ties and political marriages

Conn’s story is not just about war; it is also about strategic kinship. The saga tradition ties him into a dense web of marriages and descendants that, in reality, served to link powerful medieval dynasties back to him.

Conn’s wives and lovers often come from Leinster stock, particularly from the line of Cathair Mór, the great ancestor‑figure of that province. One tradition makes one of Cathair’s daughters Conn’s wife; another says Conn’s queen Eithne Tháebfhota is herself a daughter of Cathair Mór, which effectively binds Leinster’s ancestral line to Tara’s.

Even more important is Conn’s daughter Sadb, who is given in marriage to Ailill Ólom, an ancestor of the Munster Éoganachta. Together they beget nine sons, including Éogan Mór, from whom the Éoganacht dynasties of Munster claim descent. In some versions Éogan Mór is identified directly with Mug Nuadat, welding Conn’s great rival and his Munster son‑in‑law into a single ancestral figure.

The effect is to create a symbolic family tree in which almost every major royal house in Ireland, north and south, can claim a branch reaching back to Conn of the Hundred Battles.

The fairy bride and the barren year

If the battle stories show Conn as the archetypal warrior king, the more fantastical tales reveal him as the man constantly negotiating with the otherworld for the right to rule. One of the most striking episodes begins with his queen Eithne Tháebfhota’s death.

After Eithne dies, a woman of the Tuatha Dé Danann, Bé Chuille, is banished from the fairy host and sails to Ireland in a currach, having fallen in love with Conn’s son Art from afar. When she lands and meets Conn instead, she discovers he is without a wife and agrees to marry him on condition that Art must be banished from Tara for a year.

Conn accepts, but the men of Ireland murmur that the bargain is unjust. As Art wanders in exile, a strange blight grips the island; the fields fail, and Ireland is barren for that year. When the druids are consulted, they declare that the land’s sterility is Bé Chuille’s fault and that only the sacrifice of the son of a sinless couple at Tara will restore fertility.

The king himself sets sail in Bé Chuille’s currach, hunting the impossible child. On a mystical island of apple trees he finds a queen whose young son is the result of her only union, a boy who seems to meet the druids’ impossible criteria. Conn persuades her that if the boy bathes in the waters of Ireland, the island will be saved, and she, faced with the fate of a whole people, agrees.

When Conn brings the child back, however, the druids demand not his bath but his blood. In a rare moment where this warrior‑king refuses violence, Conn, his son Art, and the hero Fionn mac Cumhaill swear to defend the boy. At that crucial moment, a woman appears driving a cow laden with two mysterious bags. The cow is sacrificed instead of the child.

In one bag is a twelve‑legged bird; in the other, a bird with one leg. The two fight, and the one‑legged bird kills the twelve‑legged opponent. The strange woman then reveals herself as the boy’s mother and explains the omen:

- The twelve‑legged bird represents the many‑footed druids.

- The one‑legged bird represents the solitary, innocent boy, whose single “leg” is his unstained nature.

The story reads almost like a parable about the limits of priestly authority and the role of a just king who protects the innocent even when the ritual specialists demand a victim. Conn emerges not just as a man of war but as a ruler whose fate is intertwined with supernatural women, dangerous bargains and hard decisions that set him against his own wise men.

The ideal (and invented) king

For medieval writers, Conn becomes a model of what a High King should be. His reign, they insist, is marked by prosperity, good law and bountiful harvests, despite the episodes of war that fill so many pages. In some strands he shares sovereignty with Éogan Mór after the division of the island, yet still the narrative emphasises his status as the touchstone of rightful kingship, the man whose “half” of Ireland gives its name to entire regions and dynasties.

Modern scholarship, however, sees him as a pseudo‑historical construct. His supposed floruit around the second century is unattested in contemporary sources, and his career is known only from much later compilations like Lebor Gabála Érenn, genealogical tracts, and synthetic histories designed to legitimize ruling families. His very name may well derive from the collective concept of “Connachta” or from an older mythic figure adapted into a royal ancestor.

In that light, the carefully plotted division between Leth Cuinn and Leth Moga looks like an ideological map retrofitted onto legend, a story crafted to explain and justify political realities centuries later. Conn’s hundred battles may never have been fought by a single flesh‑and‑blood man, but they stand in for generations of conflict between north and south, Tara and Munster, kings and challengers.

Death on the Plain of Tara

After decades of war, treaty, and myth‑laden encounter, Conn’s end is surprisingly quiet, and oddly sinister. Tradition assigns him a reign of roughly thirty or thirty‑five years, sometimes longer depending on how the sagas are counted. For all that time he is the hub around which the island’s stories turn.

Then he is killed on the Plain of Tara by a figure who hardly exists outside the death‑notice: Tibride Tireach, king of Ulster in some versions, or another shadowy assassin in others. The sources emphasize the place more than the killer; Conn dies not in some far‑flung battlefield but at or near the ritual centre of his power, a king struck down where the Lia Fáil once roared for him.

There is an almost deliberate ambiguity to it. For a ruler whose life is crowded with omens and prophecies, the final blow is almost prosaic, as if the compilers were content to fade him out and make way for the next cycle of kings. Yet the memory of Conn refuses to fade: later dynasties echo his name, and scholars still debate how much of him is myth, how much political fiction, and whether somewhere behind the roaring stone and the night battle there might have stood a real warlord of the second‑century middle island.

Legacy of “Conn’s Half”

Whatever the historical reality, Conn of the Hundred Battles becomes, in the end, less a person than a framework. His supposed descendants, the Connachta and Uí Néill in particular, dominate the north and midlands of early medieval Ireland, and their genealogists trace their lines back to him to legitimize their claims to Tara and to high‑kingship. The very terms Leth Cuinn and Leth Moga survive as convenient ways for later writers to think about the island: a north and a south, divided by a line that might never have existed on the ground but certainly did in the imagination.

In this sense Conn’s greatest “battle” is not any single clash with Mug Nuadat or the Attacotti but the victory of his legend over the blankness of pre‑history. His story fills the void where evidence is thin with roaring stones, fairy queens, exiles returning from Spain, and night raids on mist‑drenched plains. In doing so, it offers not a reliable biography but a richly woven portrait of what early Irish writers thought a perfect king should be: warlike, favoured by omens, generous in kinship, tangled with the otherworld, and forever standing at the centre of “Conn’s Half” of the world.