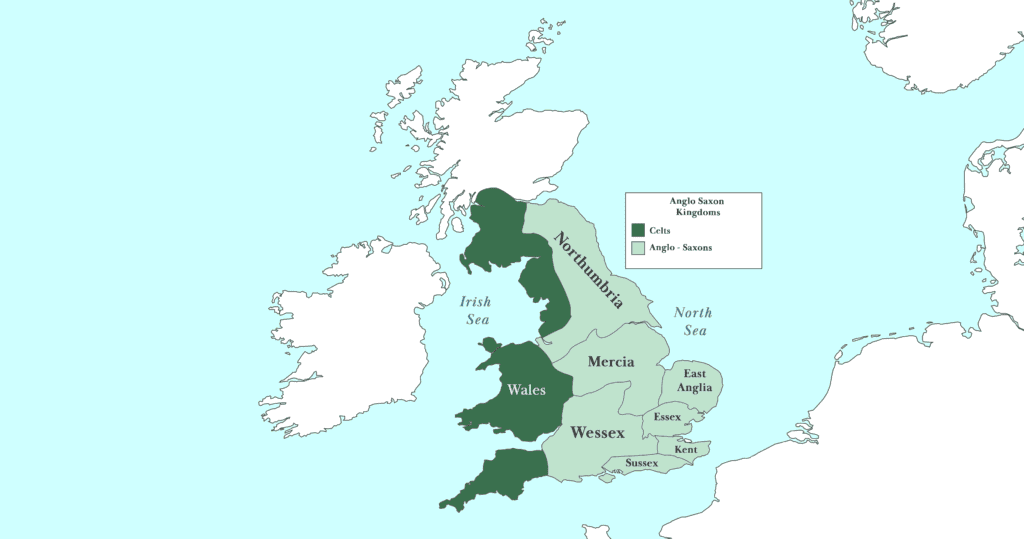

The Kingdom of Essex emerged in the 6th century as part of the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain. Its name, derived from “East Saxons,” reflects the geographic origins of its founders, who were primarily continental Saxons from Old Saxony. The kingdom’s territory encompassed what would later become the counties of Essex, Middlesex, much of Hertfordshire, and for a brief period, even parts of Kent.

The exact date of Essex’s foundation remains uncertain, but it is generally believed to have occurred around 527 CE. According to some sources, the first king of Essex was Æscwine (also known as Erchenwine), though others credit his son Sledd as the founder of the royal dynasty.

Early Settlement and Expansion

Archaeological evidence from sites like Mucking suggests that Saxon occupation of the area began as early as the 5th century. These early settlers likely coexisted peacefully with the local Romano-British population, maintaining much of the existing landscape structure. This pattern of settlement and integration would shape the kingdom’s development in the coming centuries.

As the kingdom grew, it aggregated smaller tribal groups, eventually encompassing a significant portion of southeastern England. The territory included two important Roman provincial capitals: Colchester and London. This strategic location would prove both a blessing and a curse for the kingdom throughout its history.

The Treason of the Long Knives

In the murky annals of 5th-century Britain, few events are as infamous as the Treason of the Long Knives. This legendary massacre, said to have occurred around 460 CE, epitomizes the treachery and violence that characterized the tumultuous period following Roman withdrawal from Britain.

According to medieval chronicles, the event unfolded on Salisbury Plain during a peace conference between British Celtic chieftains and Anglo-Saxon leaders. King Vortigern, the British ruler, had invited Saxon mercenaries to help defend against Pictish invasions. However, relations between the Britons and Saxons soon soured.

The Saxon leader Hengist proposed a meeting to reconcile differences. Both parties agreed to attend unarmed as a show of good faith. However, Hengist had a sinister plan. He instructed his men to conceal long knives, known as seaxes, in their boots.

As the banquet progressed and wine flowed freely, Hengist allegedly shouted, “Nemet oure Saxas” (“Take your knives”) in Saxon. At this signal, the Saxons drew their hidden weapons and slaughtered the unsuspecting British nobles. Only Vortigern was spared, likely to be held as a hostage.

This act of treachery paved the way for increased Saxon control over parts of Britain including Essex.

Political Structure and Governance

Like other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, Essex was ruled by a monarchy. The king was supported by a council known as the Witenagemot, composed of noble and ecclesiastical advisors. This system of governance allowed for a degree of stability and continuity in the kingdom’s administration.

One unique aspect of Essex’s political structure was the occasional practice of joint kingship. At times, the kingdom was ruled by co-kings, possibly to manage different regions or to balance competing factions within the royal family.

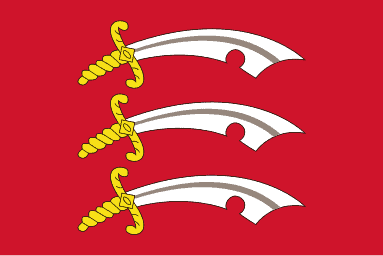

The Flag of Essex is ancient in origin and features three notched Saxon seaxes on a red field, although over recent centuries the long knives have morphed into cutlasses!

The Battle Between Christianity And Paganism

The religious history of Essex is marked by a series of conversions and reversions between paganism and Christianity, reflecting the broader religious tensions of the Anglo-Saxon period. Christianity is thought to have flourished among the Celtic Trinovantes who occupied Essex in the 4th century (late Roman period). It is not clear to what extent, if any, Christianity persisted by the time of the arrival of the pagan East Saxon kings in the sixth century.

The First Christian King

Sæberht, also known as Saberht or Sæbert, stands as a pivotal figure in the early history of Anglo-Saxon England. Ruling Essex from around 604 to 616 CE, he holds the distinction of being the first East Saxon king to embrace Christianity.

Son of King Sledd and nephew to the powerful Æthelberht of Kent, Sæberht’s reign marked a significant turning point for the kingdom. In 604 CE, he was baptized by Bishop Mellitus, following the example of his uncle and overlord, Æthelberht. This conversion was not merely a personal choice but had far-reaching consequences for the kingdom.

Under Sæberht’s rule, Essex saw the establishment of its first bishopric in London. The king allowed Mellitus to found what would become St. Paul’s Cathedral, though interestingly, it was Æthelberht who actually built and endowed the church. This act underscores the complex political dynamics of the time, with Kent exerting considerable influence over Essex.

Sæberht’s reign, however, was not without challenges. While he embraced Christianity, his three sons remained pagan. Upon his death around 616 CE, this religious divide led to significant turmoil.

Return to Paganism

However, the kingdom’s commitment to Christianity was initially tenuous. Upon Sæberht’s death in 616, his three pagan sons expelled Bishop Mellitus and reverted the kingdom to paganism, viewing Christianity as a symbol of Kentish domination. This pattern of religious flux would continue for several generations.

St Cedd Brings Back Christianity

The kingdom reconverted to Christianity under Sigeberht II the Good following a mission by St Cedd who established monasteries at Tilbury and Ithancester (Bradwell-on-Sea). Cedd was reportedly quite successful leading to his appointment as Bishop of Essex. This conversion brought about a novel approach to governance, with Sigeberht becoming a pious king, reportedly forgiving his enemies rather than executing them. This practice ultimately led to his assassination by those who disapproved of this merciful stance, the culprits were his own kinsmen, two brothers who were angry with the king “because he was too ready to pardon his enemies”

Final Conversion and Christian Consolidation

Essex reverted to Paganism again in 660 for a third time with the ascension of the Pagan King Swithelm of Essex. However, he converted in 662, but died in 664. He was succeeded by his two sons, Sigehere and Sæbbi. A plague the same year caused Sigehere and his people to recant their Christianity and Essex reverted to Paganism yet again.

This pagan rebellion was suppressed by the Christian Wulfhere of Mercia who established himself as overlord. Bede describes Sigehere and Sæbbi as “rulers […] under Wulfhere, king of the Mercians”. Wulfhere sent Jaruman, the bishop of Lichfield, to reconvert the East Saxons for a fourth and final time.

Political Dynamics and External Relations

Throughout its history, the Kingdom of Essex often found itself under the influence of more powerful neighbors. This dynamic significantly shaped the kingdom’s political trajectory and ultimate fate.

Mercian Overlordship

In the 8th century, Essex fell under the control of the powerful Kingdom of Mercia. This period saw Essex kings described as “rulers […] under Wulfhere, king of the Mercians” by the historian Bede. The Mercian overlordship brought both stability and a degree of subordination to Essex.

Incorporation into Wessex

The kingdom’s independence came to an end in 825 when it was subsumed into the expanding Kingdom of Wessex. This marked the beginning of Essex’s transition from an independent realm to a component of a larger Anglo-Saxon state.

Danish Control

Essex’s story took another turn when it became part of the Danelaw. Sometime between 878 and 886, the territory was formally ceded by Wessex to the Danelaw kingdom of East Anglia, under the Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum. This period saw significant Danish influence in the region, though it was relatively short-lived. After the reconquest by Edward the Elder the king’s representative in Essex was styled an ealdorman and Essex came to be regarded as a shire.

Byrhtnoth and the Battle of Maldon

One of the most famous events associated with Saxon Essex during this period is the Battle of Maldon in 991 CE. The battle and its hero, Ealdorman Byrhtnoth of Essex, became the subject of a renowned Old English poem. The battle, a valiant defeat against Viking invaders, exemplifies the ongoing struggles with Norse raiders in the region; Essex has a coastline with many wide river estuaries making it readily accessible to Norse longships. The battle was particularly brutal to the extent that the victorious vikings returned to their ships rather than attempt to sack the nearby town of Maldon which had been their original objective.

Archaeological Importance

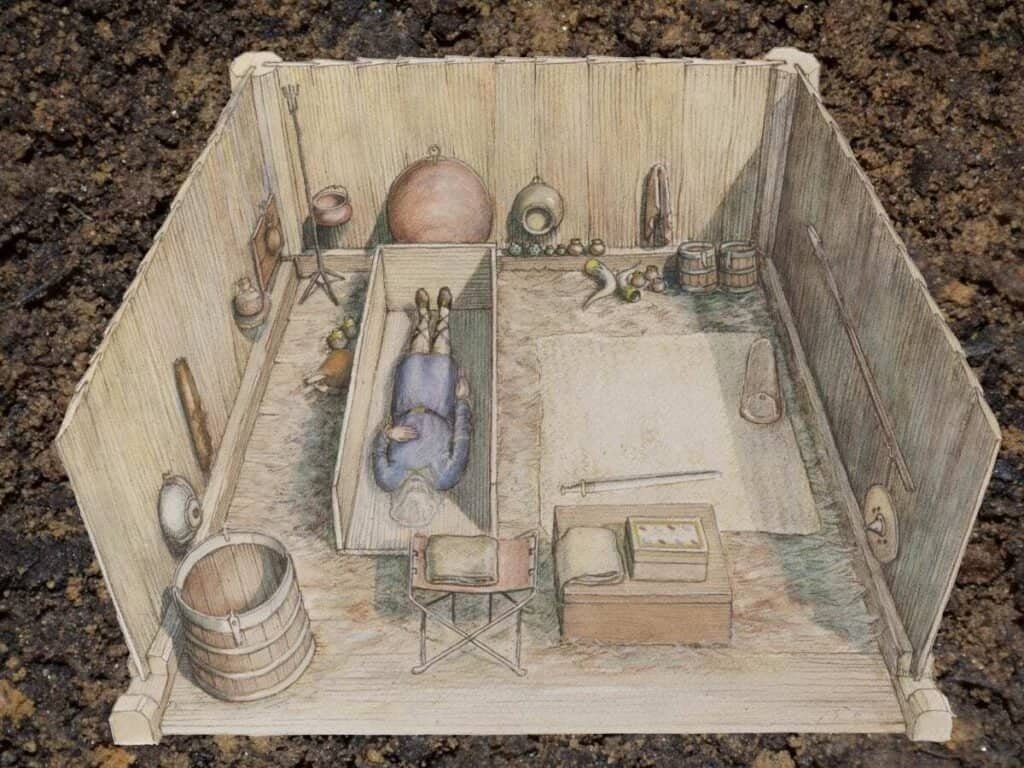

Sites like Mucking and Prittlewell have provided invaluable insights into Anglo-Saxon life, burial practices, and material culture. The Prittlewell royal Anglo-Saxon burial is a high-status Anglo-Saxon burial mound which was excavated at Prittlewell, near Southend-on-Sea, in south Essex. It was discovered in 2003 during excavations for a road-widening scheme,

Artefacts found by archaeologists in the burial chamber are of a quality that initially suggested that this tomb in Prittlewell was a tomb of one of the Anglo-Saxon Kings of Essex, and the discovery of golden foil crosses indicate that the burial was of an early Anglo-Saxon Christian. The burial is now dated to about 580 AD, and is thought that it contained the remains of Sæxa, brother of Sæberht of Essex.

Most of the excavated artefacts went on permanent display in Southend Central Museum.

https://prittlewellprincelyburial.org