The Kingdom of Strathclyde, a Celtic realm in what is now southern Scotland and northern England, played a significant role in the turbulent history of Dark Age Britain. From its origins in the post-Roman period to its eventual absorption into the Kingdom of Scotland, Strathclyde was involved in numerous conflicts that shaped the political landscape of the British Isles.

Early Conflict

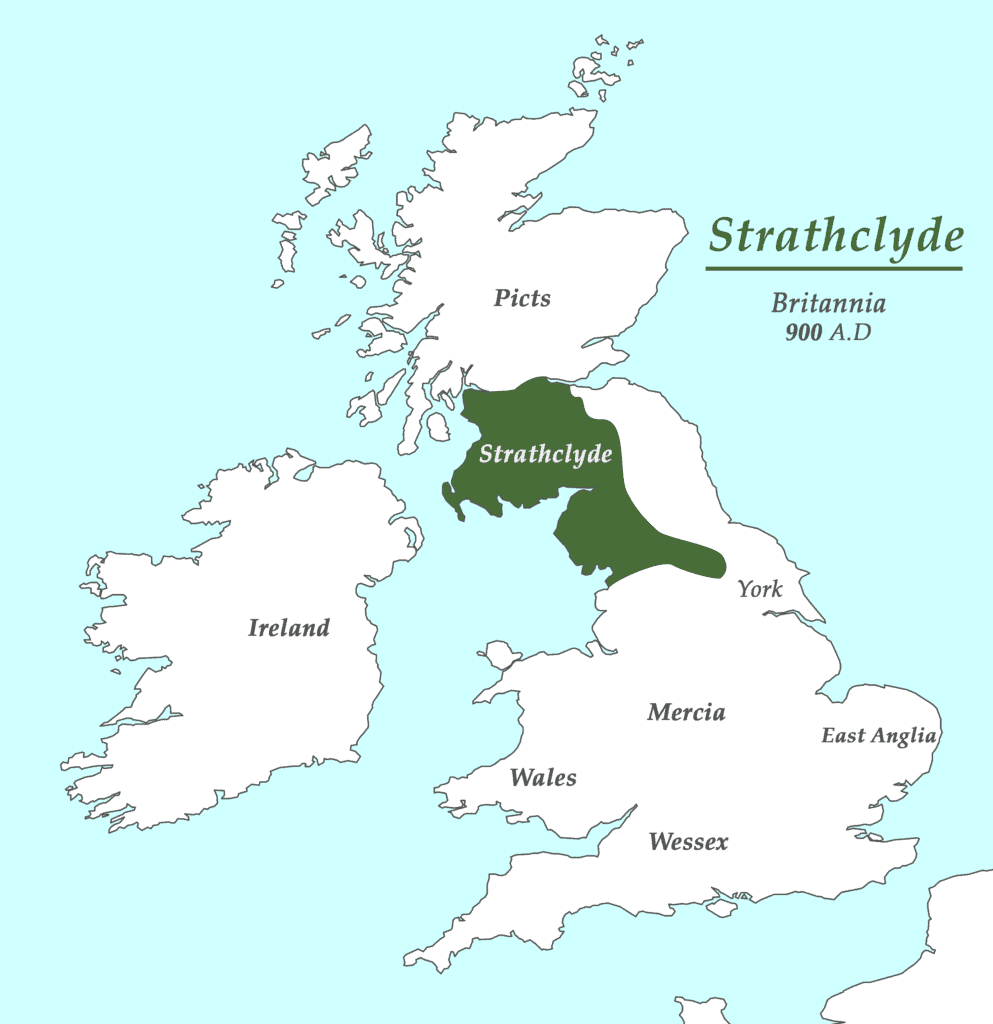

The Kingdom of Strathclyde emerged from the collapse of the Roman Empire. A Brythonic (Celtic/Welsh) realm that straddled across both sides of Hadrian’s Wall, the boundary between the Roman Empire and the unconquered North of Britain. It comprised parts of what is now southern Scotland and North West England, a region the Welsh tribes referred to as Yr Hen Ogledd (“the Old North”). At its greatest extent in the 10th century, it stretched from Loch Lomond – north of today’s Glasgow – to the River Eamont at Penrith in Cumbria.

The early history of Strathclyde is marked by its efforts to maintain independence in the face of expanding neighboring powers. One of the most significant early battles involving Strathclyde occurred around 603 CE at the Battle of Degsastan. Strathclyde was not the primary combatant, rather its ally Áedán mac Gabráin of DalRiata led a coalition of Strathclyde, DalRaida and unknown Irish allies against Æthelfrith, the ambitious Anglian king of Bernicia.

Æthelfrith, despite being outnumbered, displayed his tactical genius. He managed to outmaneuver Áedán’s larger force, using the terrain to his advantage. The fighting was fierce and relentless, with both sides suffering heavy casualties. Among the fallen was Theodbald, Æthelfrith’s brother, who perished along with his entire battle group. This loss, however, did not deter the Bernician king. Instead, it seemed to fuel his determination, as he led his men with even greater ferocity.

As the day wore on, the tide of battle turned decisively in favor of Æthelfrith. Áedán’s army, despite its numerical superiority, began to crumble under the relentless assault of the Bernician forces. In the end, the Gaelic king was forced to flee the battlefield, leaving behind a trail of dead and dying warriors.

Æthelfrith’s victory cemented Bernician dominance and effectively halted Gaelic expansion southwards into Anglo-Saxon territories.

The arrival of the Vikings

The Viking Age brought new challenges to Strathclyde. In 870 CE, the Kingdom of Strathclyde faced a pivotal moment in its history when Viking chiefs Amlaíb Conung and Ímar laid siege to Alt Clut, the capital fortress of the Strathclyde. Alt Clut, also known as Dumbarton Rock, was a formidable stronghold that had withstood previous attacks and served as the center of power for the last remaining Brittonic kingdom outside of Wales.

The siege of Alt Clut was unprecedented in its duration and intensity. For four long months, the Viking forces, led by Amlaíb and Ímar, besieged the fortress. This extended period was highly unusual for Viking warfare in the British Isles, highlighting the strategic importance and defensive strength of Alt Clut.

The natural defenses of Alt Clut (Dumbarton Rock) played a crucial role in the prolonged resistance. Rising 240 feet high with twin peaks, the volcanic rock formation was surrounded by the Rivers Clyde and Leven, making it an ideal defensive position. The fortress had previously survived coordinated assaults, including one by Angles and Picts in 756.

Despite its strong defenses, Alt Clut ultimately fell to the Viking invaders. The defenders held out valiantly for four months until their water supply ran dry, forcing them to capitulate. The Vikings’ victory was likely due to their ability to seize the lower part of the rock where the well was located, cutting off the water supply to the defenders above them.

Following the siege, the Vikings plundered the fortress and took many defenders captive. Numerous prisoners were transported to the Norse slave markets of Dublin and sold into slavery, dealing a severe blow to the kingdom’s population and leadership. The fate of King Arthgal ap Dyfnwal, who ruled Strathclyde at the time of the siege, remains uncertain. He may have escaped to Pictland or been among the captives taken to Dublin.

In the aftermath of the siege, Strathclyde began to fall increasingly under the influence of the emerging Scottish Kingdom of Alba although it would retain its independence.

Alliances and Conflicts in the 10th Century

As the 10th century dawned, Strathclyde found itself navigating a complex web of alliances and conflicts. According to the Fragmentary Annals of Ireland, Æthelflæd, Lady of the Mercians, formed an alliance with Strathclyde and Scotland against the Vikings. This period saw Strathclyde make substantial territorial gains, some at the expense of Norse settlers.

In 920 CE, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle claims that the kings of Britain, including the unnamed king of Strathclyde, submitted to Edward the Elder of Wessex. However, historians are skeptical of this claim, suggesting it was more likely a peace settlement than an act of submission.

The Battle of Brunanburh: A Turning Point in British History

In 937 CE, the fields of Brunanburh witnessed one of the bloodiest and most significant battles in Anglo-Saxon history. This clash pitted King Æthelstan of England against a formidable alliance of Norse, Scottish, and Strathclyde forces led by Olaf Guthfrithson, Constantine II, and Owain, respectively.

The conflict arose from Æthelstan’s efforts to unify England under his rule, which threatened the interests of neighboring kingdoms. In response, a massive invasion force gathered in Ireland, crossing the Irish Sea to challenge Æthelstan’s authority.

The battle itself was a brutal affair, lasting from dawn until dusk. Contemporary accounts describe it as “immense, lamentable and horrible, savagely fought”. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle’s poem vividly portrays the carnage, stating that “never was there more slaughter on this island, never yet as many people killed before this”.

Æthelstan’s forces, comprising West Saxons and Mercians, ultimately prevailed against the invaders. The victory was decisive, with five kings, seven earls, and countless soldiers falling on the battlefield. Olaf Guthfrithson barely escaped with his life, fleeing by ship to Dublin, while Constantine II retreated to Scotland, having lost his son in the conflict. Owain, King of Strathclyde, was likely killed in the battle, dealing a severe blow to the kingdom’s leadership.

The Brunanburh campaign demonstrated both the military capabilities and the limitations of Strathclyde. While able to field a significant force as part of the alliance, the kingdom ultimately could not overcome the power of the emerging English state under Æthelstan.

Aftermath of Brunanburh and English Invasions

Just eight years after Brunanburh, the political landscape of Britain was forever altered by a brutal campaign led by Edmund I, King of England. The young monarch, barely into his mid-twenties, launched a devastating raid into the territory of Strathclyde.

Edmund’s invasion was swift and merciless. His forces swept through Cumbria, leaving destruction in their wake. The campaign reached its horrifying climax when Edmund captured two sons of Dyfnwal ab Owain, the King of Strathclyde. In a shocking act of cruelty, Edmund ordered the young princes to be blinded.

This brutal mutilation was far more than a simple act of violence. By blinding Dyfnwal’s sons, Edmund was employing a calculated political strategy. In the medieval world, physical wholeness was often seen as a prerequisite for kingship. By depriving these princes of their sight, Edmund effectively eliminated them as potential heirs to the Strathclyde throne. This act was a deliberate attempt to weaken Strathclyde’s royal line and destabilize the kingdom’s future.

In the aftermath of this brutal campaign, Edmund made a strategic decision that would reshape the political landscape of northern Britain. He handed control of Strathclyde to Malcolm I, the King of Alba (Scotland), in exchange for a promise of military support. This move effectively made Strathclyde a buffer state between England and Scotland, while also binding the Scottish king more closely to English interests.

For Strathclyde, the raid of 945 CE marked the beginning of a long decline. While the kingdom would continue to exist, subservient to Alba, for several more decades, it never fully recovered from Edmund’s devastating attack. The events of that year set in motion a chain of events that would eventually lead to Strathclyde’s absorption into the expanding Scottish kingdom.

The fall of the kingdom

Sometime between 1018 and 1054 CE, Strathclyde was finally conquered by the Scots, most likely during the reign of Máel Coluim mac Cináeda (Malcolm II of Scotland), who died in 1034.

The last recorded military engagement involving Strathclyde occurred in 1054 CE, when Edward the Confessor of England sent Earl Siward of Northumbria against the Scots. The campaign included support for “Malcolm son of the king of the Cumbrians,” possibly a claimant to the Strathclyde throne. This event marks the final appearance of Strathclyde as a distinct political entity in historical records.