Few legends have traveled as far and wide, or evolved as dramatically, as that of St. George. From his origins as a Christian martyr in the Roman Empire to his transformation into the dragon-slaying patron saint of England, St. George’s story is a tapestry woven from threads of faith, folklore, and the shifting needs of societies across continents and centuries.

Origins: The Historical George

The true details of St. George’s life are shrouded in mystery. Most early accounts agree that he was born to Christian parents of noble standing, with some traditions placing his birth in Cappadocia (modern-day Turkey) and others in Lydda (now Lod, Israel/Palestine). After his father’s death, George’s mother returned with him to her homeland, where he was raised in the Christian faith.

George became a soldier in the Roman army, rising to the rank of tribune or a member of the elite Praetorian Guard under Emperor Diocletian. During a period of intense persecution of Christians, George refused to renounce his faith or offer sacrifices to the Roman gods. For this, he was arrested, tortured, and ultimately beheaded – his martyrdom believed to have occurred around 303 AD, likely at Lydda.

The earliest written fragments about George date from the 5th century, though his cult was already widespread by then. Pope Gelasius I, in 494 AD, acknowledged George among those saints “whose names are justly reverenced among men, but whose actions are known only to God”. This admission of uncertainty did nothing to diminish his popularity.

The Martyr’s Tale: Early Legends

In the centuries following his death, stories of George’s steadfastness under torture and his miraculous endurance circulated widely in Christian communities from Armenia to Nubia, and from Rome to Ethiopia. The earliest legends, including those in Coptic, Syriac, and Greek, focus on his confrontation with a pagan ruler – sometimes called Dadianus, later rationalized as Diocletian – over the worship of idols. George, unwavering in his faith, distributed his wealth to the poor and declared himself a “soldier of my Lord Jesus Christ the King of heaven,” openly challenging the authorities.

These stories, while dramatic, do not yet feature a dragon. Instead, they present George as a model of Christian virtue: courageous, generous, and unyielding in the face of oppression.

The Dragon Enters: Transformation in Medieval Europe

The now-iconic episode of St. George and the Dragon emerged much later, first appearing in 11th-century Georgian sources and spreading rapidly through the Byzantine world. The story’s migration westward was propelled by the Crusades, as returning knights brought with them tales of George’s miraculous interventions on the battlefield and his role as a heavenly protector of Christian warriors.

The Golden Legend

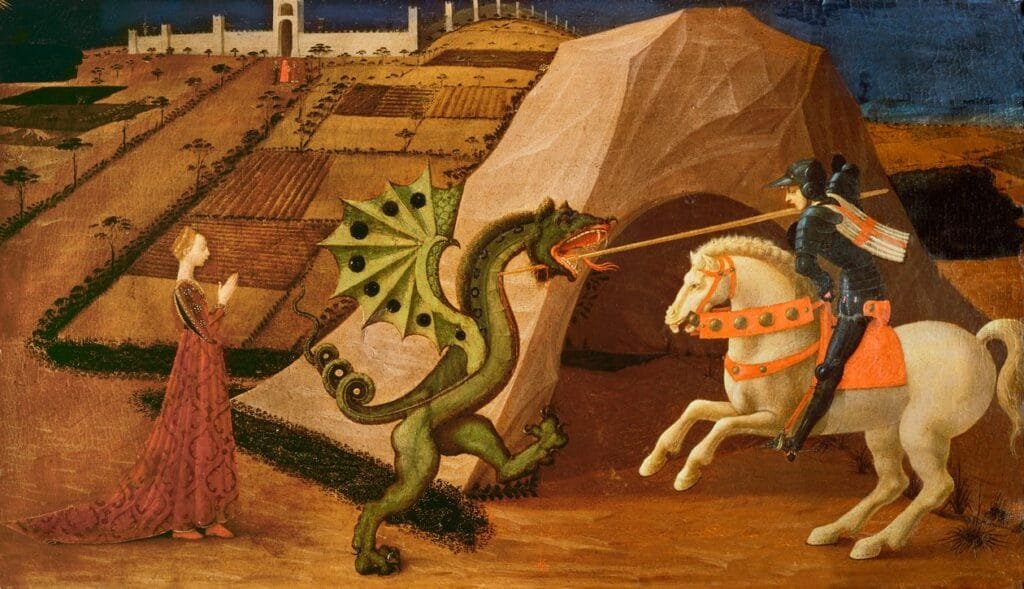

The most influential version of the dragon story comes from the Legenda Aurea (Golden Legend), compiled by Jacobus de Voragine in the 13th century. Here, the action is set in the city of Silene, “Libya” – a term medieval writers used for much of North Africa. The city is terrorized by a venomous dragon living in a nearby pond, whose breath poisons the countryside. To appease the beast, the townsfolk offer it two sheep a day. When their flocks run dry, they resort to sacrificing their own children, chosen by lottery.

One day, the king’s daughter is selected. Clad in bridal finery, she is led to the dragon’s lair. At this moment, St. George arrives. The princess pleads with him to flee, but George refuses. As the dragon emerges, George makes the Sign of the Cross and charges on horseback, wounding the monster with his lance. He then binds the dragon with the princess’s girdle, leading the now-docile beast back to the city. George offers to slay the dragon if the townspeople convert to Christianity. Fifteen thousand men, including the king, are baptized. George then beheads the dragon, and the grateful king builds a church on the site, from whose altar a healing spring flows.

Roots and Parallels

The dragon episode, while now inseparable from St. George, draws on much older mythological motifs. Scholars have noted its resemblance to the Greek story of Perseus rescuing Andromeda from a sea monster, as well as to other tales of heroes confronting chaos in the form of serpents or dragons. The narrative’s journey from pagan myth to Christian legend reflects the adaptability of folklore and the ways in which new faiths repurposed ancient symbols.

Symbolism and Spread

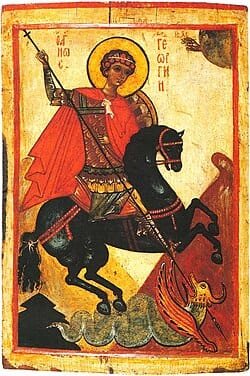

The legend of St. George and the Dragon quickly became a favorite subject in medieval art and literature, symbolizing the triumph of good over evil, faith over unbelief, and order over chaos. The image of the mounted saint, lance poised against a writhing dragon, adorned churches, manuscripts, and banners across Christendom.

The story’s popularity was further cemented by its inclusion in the Golden Legend, one of the most widely read books of the Middle Ages. In England, William Caxton’s 15th-century translation ensured that the tale became part of the national consciousness. The motif of the dragon-slayer was also embraced in Eastern Christianity, where icons of St. George became ubiquitous.

Crusading Origins and Christian Symbolism

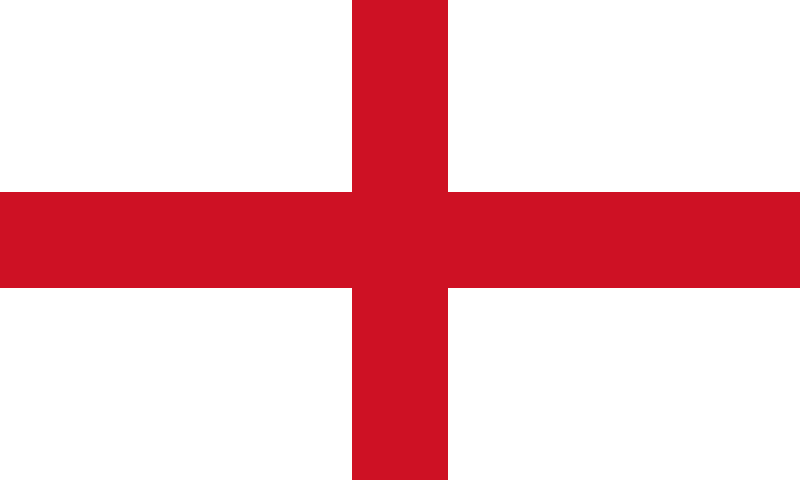

The red cross of Saint George – a simple red cross on a white background – became a prominent symbol in medieval Europe due to its association with crusading, Christian identity, and later, national and civic pride.

The red cross first gained widespread recognition during the Crusades. From the late 11th century, crosses of various colors were used to identify different groups of crusaders. By the time of the Third Crusade (late 12th century), the red-on-white cross had become particularly associated with English and French crusaders, serving as a visible sign of their Christian faith and their commitment to the holy cause. The cross itself symbolized martyrdom, sacrifice, and the willingness to fight for Christianity.

From Genoa to England: A National Symbol

St. George’s association with England is a product of both legend and political necessity. During the Crusades, English knights adopted George as a heavenly patron, inspired by stories of his miraculous appearances at Antioch and Jerusalem. By the 14th century, St. George had become the premier military saint of England, his red cross on a white field adopted as the national flag – a symbol first popularized by Genoese merchants and crusaders.

English kings and nobles invoked George’s name in battle, and the Order of the Garter, the highest order of English chivalry, was dedicated to him. By the reign of Edward III, St. George was firmly established as England’s patron saint, his feast day celebrated on April 23rd.

The Legend Evolves: Romance and Reinvention

As the legend spread, it was embellished and reinterpreted. In Richard Johnson’s Seven Champions of Christendom (1596), the rescued princess is named Sabra, and George marries her, fathering English children – one of whom becomes the legendary Guy of Warwick. The story became a vehicle for chivalric ideals and national pride, with George depicted as the perfect Christian knight.

In Edmund Spenser’s epic poem The Faerie Queene (1590), St. George appears as the Red Cross Knight, battling a dragon that represents sin and heresy, while the princess Una symbolizes the true (Protestant) church. Here, the legend is recast as an allegory for the religious struggles of Elizabethan England.

Legacy: A Universal Hero

St. George’s appeal transcends religious and cultural boundaries. He is venerated not only by Christians – both East and West – but also by Muslims, who know him as Al-Khidr, a righteous servant of God. His story has been retold in countless languages, adapted to local traditions, and celebrated in art, literature, and popular culture.

Relics attributed to St. George are housed in churches from Portugal to Palestine, and his image adorns everything from Russian icons to English coins. He is the patron saint of countries as diverse as Georgia, Ethiopia, and Catalonia, as well as of soldiers, scouts, and sufferers of leprosy.

The legend of St. George endures because it speaks to universal themes: the courage to stand up for one’s beliefs, the willingness to confront evil, and the hope that even in the darkest times, deliverance is possible. Whether as a martyr facing the might of Rome, a knight charging a dragon, or a symbol of national identity, St. George remains a figure of inspiration and wonder. Also, his story reminds us that legends are not static – they grow, migrate, and transform, shaped by the needs and dreams of each generation.