In the spring of 1182, the greatest city in Christendom became the scene of one of the most shocking outbursts of anti-Christian violence in the medieval world. Constantinople, proud capital of the Byzantine Empire, had long been a cosmopolitan hub where merchants from Italy, envoys from the Crusader states, and Orthodox citizens mingled in the crowded harbors and bustling marketplaces. But beneath the surface, tension had been building for decades between the Greeks of the city and the so-called “Latins” – the catch-all term Byzantines used for Western Europeans, particularly Italians.

Constantinople in the Twelfth Century: A City of Tension

By the late twelfth century, Constantinople was the beating heart of an empire that still possessed immense wealth, though it was increasingly surrounded by threats.

- To the west, the rising powers of Venice, Genoa, and Pisa dominated Mediterranean trade. Their merchants, who had once been granted privileges in Byzantium as allies, now seemed like parasites bleeding the empire’s economy.

- To the east, the Seljuk Turks and the shadow of a resurgent Islamic world pressed against Byzantine frontiers.

- To the north, restless steppe peoples and ambitious rivals in the Balkans threatened imperial borders.

Within the city itself, this pressure manifested as economic inequality and xenophobic resentment. Italian merchants enjoyed extraterritorial rights in Constantinople: they lived in their own quarters, were exempt from certain taxes, and often used their naval strength to secure concessions from the emperors. Many Greeks saw them as arrogant interlopers who siphoned off trade profits while showing little loyalty to Byzantium.

The Venetians were especially hated. Their merchant fleet was so vital that emperors alternately courted and feared them. But by the 1170s, their rivals – the Pisans and Genoese – had also secured lucrative privileges. Their trading colonies sprawled along the shores of the Golden Horn, miniature Italian republics nestled inside the Byzantine capital.

This uneasy coexistence would collapse in 1182.

The Rise of Andronikos Komnenos

The massacre cannot be understood without the figure of Andronikos I Komnenos, one of Byzantium’s most colorful and controversial rulers.

Born around 1118 into the imperial Komnenos dynasty, Andronikos lived much of his life as a restless adventurer, conspirator, and exile. Handsome, charismatic, and reckless, he became infamous for his affairs (including with the niece of Manuel I Komnenos, the reigning emperor), his daring escapes from prison, and his wanderings across the Middle East and beyond.

By the early 1180s, Constantinople was under the rule of Empress Maria of Antioch, widow of Emperor Manuel I. She served as regent for her young son, Alexios II Komnenos, who had inherited the throne at just 11 years old. Maria herself was a Westerner — a Latin from the powerful principality of Antioch. This already made her suspect in the eyes of many Byzantines. Worse still, she leaned heavily on the Italian merchant communities, especially the Pisans and Genoese, for political and financial support.

To the Greek population, this Latin empress and her Italian allies became symbols of foreign domination. Resentment seethed.

Enter Andronikos. Returning from exile, he portrayed himself as the champion of the “true” Byzantine people against corrupt Latin influences. He promised to end exploitation by foreign merchants and to restore the empire’s dignity. His cause resonated powerfully. By 1182, mobs in Constantinople were ready to act on his rhetoric.

The Spark of Violence

When Andronikos marched on Constantinople in the spring of 1182, popular discontent erupted. As his forces approached, the capital fell into chaos. Supporters of the regency tried to rally, but they were vastly outnumbered by citizens who saw Andronikos as their savior.

In this volatile atmosphere, the Latin communities became the scapegoat. Centuries of cultural suspicion, economic resentment, and political manipulation came to a head. Byzantine chroniclers describe how mobs poured into the Italian quarters along the Golden Horn. What followed was a massacre.

The Massacre Unfolds

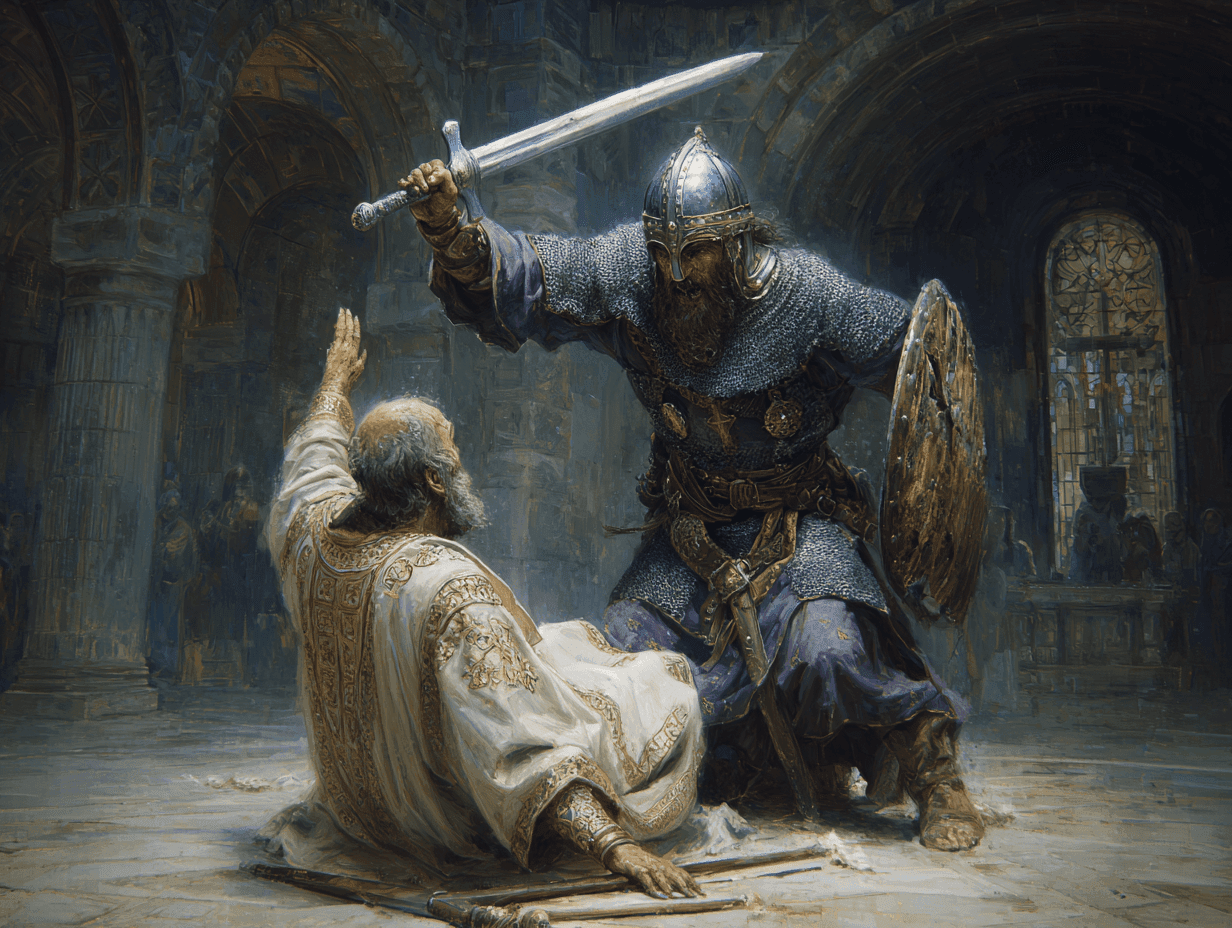

The details are gruesome. Western accounts speak of wholesale slaughter: men, women, and children cut down without mercy. Priests were beheaded at the altar; nuns were raped; infants were dashed against walls.

- Churches belonging to the Latin community, including those of the Venetians, Genoese, and Pisans, were burned.

- Merchants were dragged from their houses and butchered in the streets.

- Even the papal legate, Cardinal John, was reportedly paraded through the city before being decapitated.

The numbers are uncertain. Some chroniclers speak of tens of thousands killed, though medieval figures are often exaggerated. A more cautious estimate suggests several thousand perished. Whatever the exact toll, it was a bloodbath that shocked the Mediterranean world.

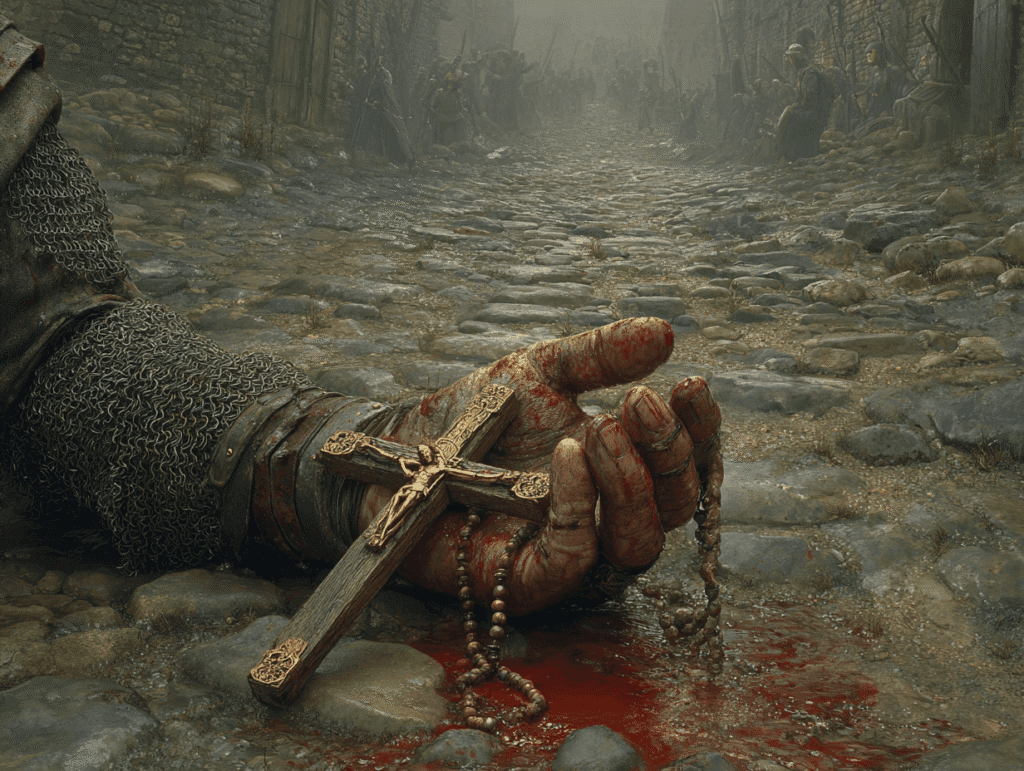

The Venetian and Genoese fleets were absent at the time, leaving their countrymen defenseless. Survivors who managed to escape by ship carried tales of horror back to Italy, fueling deep resentment against Byzantium.

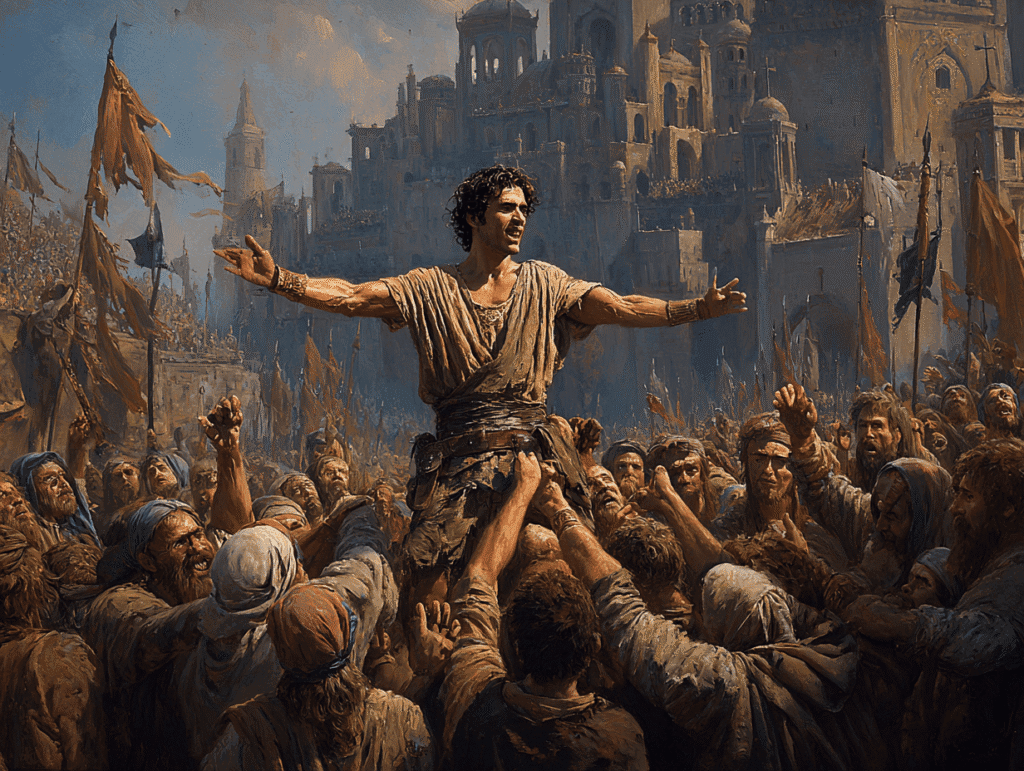

Andronikos, for his part, did little to restrain the violence. If anything, he allowed it as a means of consolidating his populist image: the man who had purged the empire of hated foreigners. With the massacre, his path to power was cleared. He soon entered Constantinople in triumph and seized the throne, ruling as emperor from 1183 to 1185.

Motives Behind the Massacre

The massacre was not a random outbreak of mob fury. It was the culmination of several interlocking motives:

- Economic resentment – Italian merchants had cornered much of Constantinople’s trade, often enjoying privileges at the expense of local Greek merchants. Their wealth and influence bred envy.

- Political manipulation – Andronikos skillfully harnessed anti-Latin sentiment to delegitimize the regency of Maria of Antioch and present himself as a patriotic alternative.

- Religious hostility – The Great Schism of 1054 had already poisoned relations between Orthodox Byzantines and Catholic Latins. Mutual accusations of heresy and arrogance stoked the flames.

- Social tension – Constantinople was a city of nearly half a million people, a sprawling urban mass where food shortages, inequality, and unrest were constant dangers. The Latin communities were visible targets for popular anger.

In short, the massacre was both a symptom of Byzantine decline and a political tool wielded by an ambitious usurper.

The Shockwaves Across Christendom

News of the massacre spread quickly, carried by survivors to Italy and beyond. The outrage was immense.

- Venice in particular vowed revenge. The Venetians had long been the most powerful Western community in Constantinople, and the massacre of their countrymen would not be forgotten.

- The Papacy was horrified at the killing of clergy and the papal legate. This further deepened mistrust between Rome and Constantinople.

- The Crusader states in the Levant, dependent on both Byzantine and Western support, saw their fragile position undermined by the widening rift.

The massacre confirmed Western suspicions that Byzantines were treacherous and unreliable allies. It also convinced many Italians that Byzantine wealth could only be obtained by force.

In this sense, the bloodshed of 1182 planted seeds that would bear fruit two decades later, when the Fourth Crusade turned its fleet against Constantinople. The sack of 1204, which devastated the city and fractured the empire beyond repair, cannot be understood without the memory of 1182 haunting Western minds.

Andronikos’ Brief and Bloody Rule

Having seized power, Andronikos I Komnenos proved himself both brilliant and brutal. At first, his rule had real reforms: he cracked down on corruption, sought to limit the power of the aristocracy, and tried to stabilize the empire. But his reliance on terror soon alienated supporters.

Executions, mutilations, and purges became commonplace. Nobles were blinded or strangled; enemies disappeared into dungeons. Andronikos’ paranoia grew until his regime resembled a reign of terror.

In 1185, just three years after the massacre, his enemies struck back. When a Norman invasion of Thessalonica provoked widespread anger at his failures, a coup toppled him and he was captured.

The Death of Andronokos

The execution of Andronikos I Komnenos unfolded as a scene of raw brutality, unlike any other in Byzantine history. Dragged into the streets of Constantinople, the deposed emperor faced not only the vengeance of political rivals but the unbridled fury of a populace that had come to despise him. What began as a display of punishment quickly descended into a spectacle of chaos, as the crowd jeered and clawed at his broken body.

The once-mighty ruler was paraded like a common criminal, mocked and spat upon, his imperial dignity shattered with every step. His tormentors chained him and subjected him to grotesque humiliations before fastening him to the execution device, where agony was prolonged as if serving as both justice and entertainment. Ordinary citizens, enraged by years of cruelty and misrule, participated in his downfall, striking him with their own hands, a rare opportunity to vent centuries of bitterness upon a single man.

By the time death finally claimed him, his body stood as a twisted symbol of vengeance fully spent. Andronikos’ end was not a quiet passing but a violent unraveling, a warning to future rulers that fear and tyranny eventually consume themselves when the crowd seizes its voice.

His bloody rise and fall were inseparable from the massacre of 1182. The violence that had brought him to power ultimately consumed him.

The Massacre in Retrospect

Looking back, the Massacre of Latins in Constantinople was a turning point in medieval history. It crystallized the deepening estrangement between Byzantium and the Latin West.

- For Byzantium, it demonstrated the fragility of imperial authority and the dangerous power of populist resentment. The empire could no longer manage its foreign allies without risking internal explosion.

- For the West, it confirmed suspicions that Byzantium was an unreliable partner. Italians in particular came to view the empire as both enemy and prize.

- For both, it poisoned the atmosphere of cooperation that had once made the First Crusade possible.

When the Fourth Crusade captured Constantinople in 1204, Western chroniclers explicitly invoked the memory of 1182 as justification. “They slaughtered us then,” the logic went, “and now justice has been served.” In this sense, the blood spilled in 1182 foreshadowed the greater catastrophe that would follow.

When we think of Constantinople, we often imagine its glittering domes and golden mosaics. But in 1182, its streets ran red, and the empire that prided itself on being the beacon of Christian civilization revealed its darker side. From that moment on, the dream of a united Christendom was dead, and the road to 1204 lay open.