The year 1054 marked a pivotal moment in the history of Christianity, as tensions that had been simmering for centuries finally boiled over into a formal split between the Western and Eastern churches. This event, known as the Great Schism, would reshape the religious landscape of Europe and the Mediterranean for centuries to come.

A Tale of Two Empires

To understand the events of 1054, we must first look back to the division of the Roman Empire in 285 AD. Emperor Diocletian had split the vast territory into Western and Eastern halves for easier administration. While this decision was initially meant to be temporary, it set the stage for a gradual divergence in culture, language, and religious practices.

As the Western Roman Empire crumbled under the weight of barbarian invasions, the Eastern Empire, centered in Constantinople, flourished. This disparity in fortunes only served to widen the growing chasm between East and West.

Seeds of Discord

Over the centuries, several key issues emerged that would eventually lead to the Great Schism:

- Papal Authority: The Bishop of Rome (the Pope) claimed universal jurisdiction over all Christians, a notion rejected by the Eastern patriarchs.

- Filioque Clause: A theological dispute arose over the procession of the Holy Spirit, with the Western Church adding the word “filioque” (and the Son) to the Nicene Creed.

- Liturgical Practices: Differences in worship styles, including the use of leavened or unleavened bread in the Eucharist, became points of contention.

- Language and Culture: As Latin became dominant in the West and Greek in the East, communication and mutual understanding became increasingly difficult.

The Powder Keg Ignites

In the spring of 1054, Pope Leo IX sent a delegation to Constantinople, led by the forceful and uncompromising Cardinal Humbert of Silva Candida. Their ostensible mission was to smooth over relations with the Eastern Church, but events would soon take a dramatic turn.

Awaiting the papal legates in Constantinople was Patriarch Michael Cerularius, a proud and stubborn man who had already taken provocative actions against the Western Church. In 1053, he had ordered the closure of all Latin churches in Constantinople, a move that heightened tensions between East and West.

From the moment Cardinal Humbert arrived in Constantinople, it was clear that reconciliation would be difficult. The cardinal, known for his fiery temperament, immediately clashed with Cerularius over matters of protocol and theology.

Negotiations quickly broke down as both sides refused to budge on key issues. Humbert, frustrated by what he perceived as Eastern intransigence, decided to take drastic action.

A Dramatic Excommunication

On the morning of July 16, 1054, Cardinal Humbert and his delegation marched into the Hagia Sophia, the great cathedral of Constantinople. As the faithful gathered for the Divine Liturgy, Humbert strode up to the altar and placed a bull of excommunication upon it.

The document, written in Humbert’s characteristically inflammatory style, declared Patriarch Michael Cerularius and his followers to be anathema – cut off from the true Church. The shocked congregation watched in stunned silence as the papal legates turned on their heels and marched out of the cathedral.

Enraged by this affront, Patriarch Cerularius quickly convened a synod of Eastern bishops. On July 20, 1054, they issued their own excommunication against Cardinal Humbert and his associates. Notably, they did not excommunicate Pope Leo IX himself, as news had not yet reached Constantinople that the pontiff had died three months earlier.

A Schism Takes Root

In the immediate aftermath of these mutual excommunications, few realized the long-lasting impact these actions would have. Many hoped that the breach could be healed, as similar conflicts had been in the past.

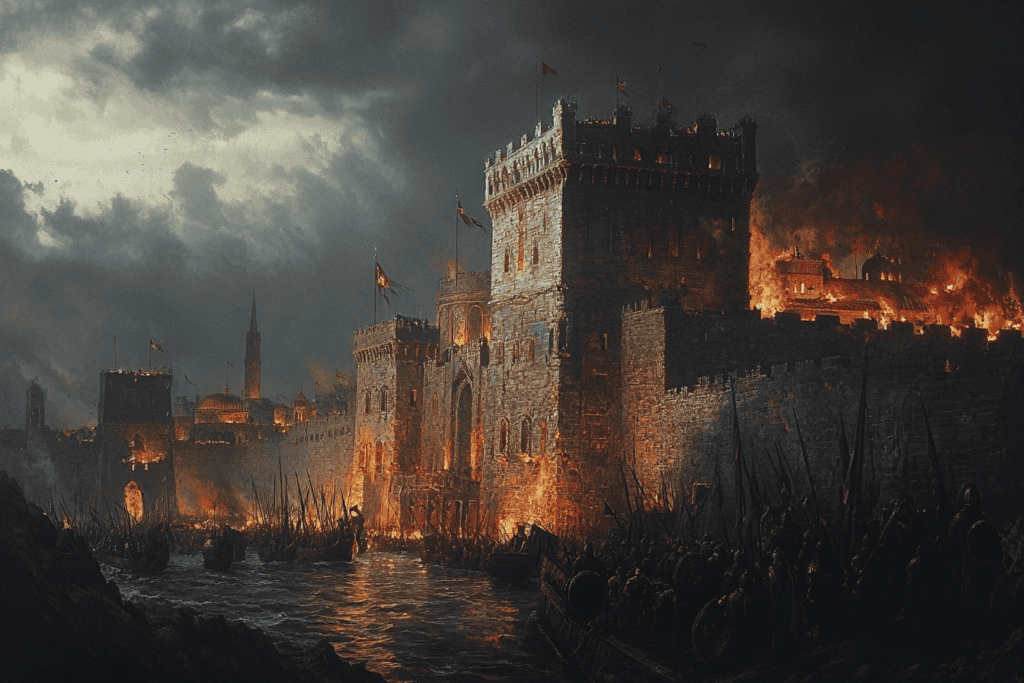

However, as the years passed, the split between East and West only deepened. The Fourth Crusade’s sack of Constantinople in 1204 drove an even greater wedge between the two churches, cementing the schism for centuries to come.

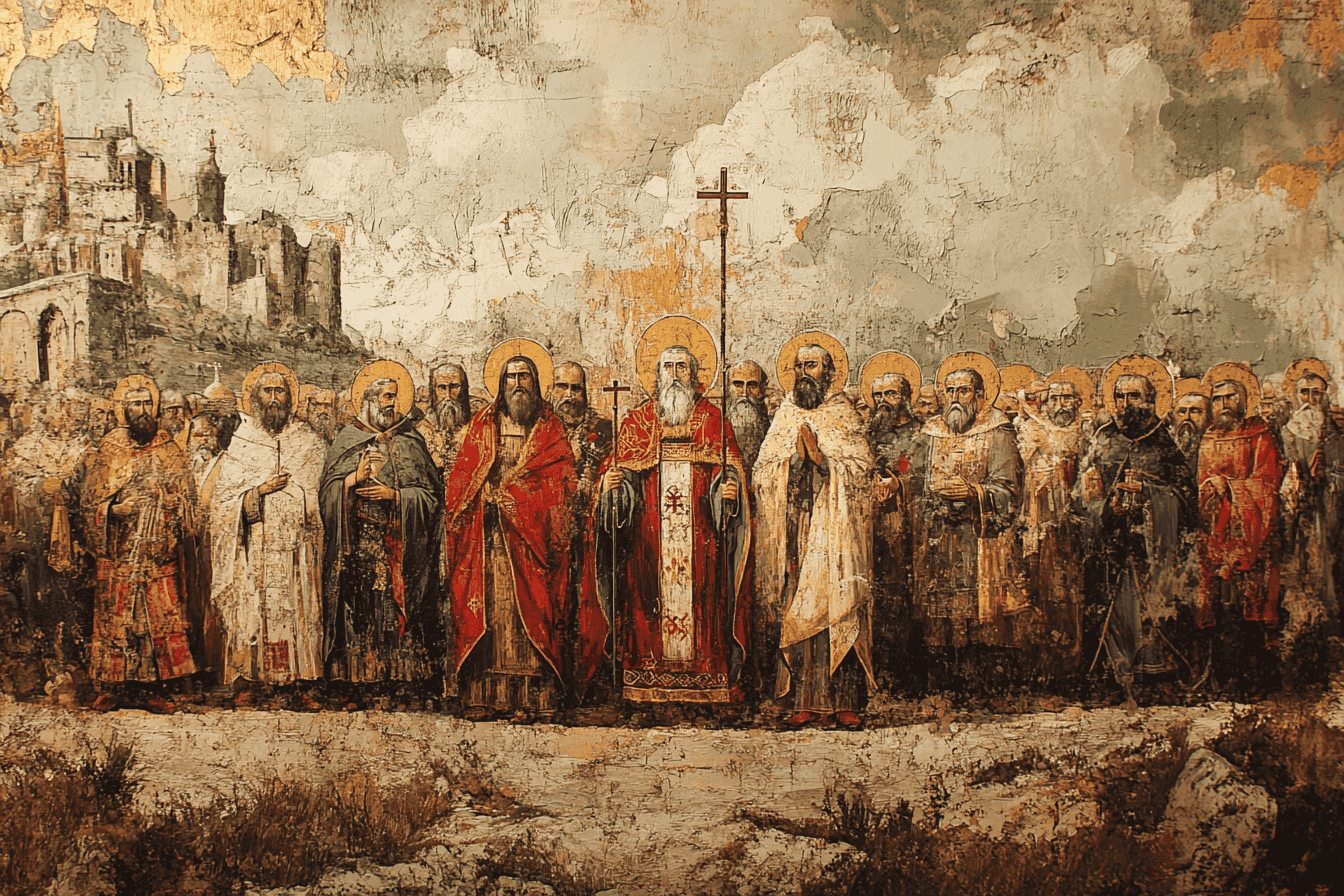

Two Churches Emerge

The Great Schism of 1054 resulted in the formation of two distinct branches of Christianity:

- The Roman Catholic Church: Centered in Rome and led by the Pope, it maintained its claim to universal authority over all Christians.

- The Eastern Orthodox Church: Comprised of several autocephalous (self-governing) churches, united in theology and tradition but without a single central authority.

A Divided Christendom

The Great Schism fundamentally altered the religious landscape of Europe and the Mediterranean. The division between Catholic and Orthodox Christianity roughly followed the old borders of the Western and Eastern Roman Empires, with some exceptions. This split had profound implications for the future development of European civilization, influencing everything from art and architecture to politics and philosophy.

Over the centuries, there were numerous attempts to heal the rift between the Catholic and Orthodox churches. However, these efforts often faltered due to deep-seated mistrust and fundamental disagreements over doctrine and authority.

It wasn’t until 1965, nearly a millennium after the original schism, that Pope Paul VI and Patriarch Athenagoras I finally lifted the mutual excommunications of 1054. While this gesture was largely symbolic, it marked an important step towards improved relations between the two churches.

Of course, this “overview” of the Great Schism is very much simplified. First, often when there were debates in the East, those Churches went to the Pope to help resolve them and this was successful more often than not. But when the East rose in prominence above the West, and Constantinople because the premiere city of the Empire rather than Rome, the Church as a whole recognized the Patriarch of Constantinople as being The First Among Equals, replacing the Pope. This did not go down well in the West where the Church of Rome was the only Church and the Pope had come to view himself as the “head of the Church.” This, actually, was the real problem that led to schism. Of course, this was greatly aggravated by the West making unilateral decisions regarding the Church as a whole such as unmarried clergy and, worst of all, the acceptance of the already disapproved filioque that determined the procession of the Holy Spirit from both the Father and the Son. The Council that rejected this heresy had made clear that NO Church could overcome the Council’s decision on any matter without another Council to address the question. The West chose to deny that ruling though that Church participated in the Counsel at the time.

Perhaps the most clear acknowledgment of the failure of the West to remain faithful to the Christian Church’s doctrines and beliefs is the fact that there was never a Protestant reformation in the East.