In the winter of 1237, a storm of unparalleled ferocity descended upon the fragmented principalities of Kievan Rus’. The Mongols, led by Batu Khan, grandson of Genghis Khan, unleashed their military machine on the East Slavic lands, marking the beginning of their westward expansion into Europe. This invasion not only devastated the Rus’ principalities but also set the stage for the Mongol Empire’s influence over Eastern Europe for centuries to come.

Prelude to Invasion: The Rise of the Mongol Empire

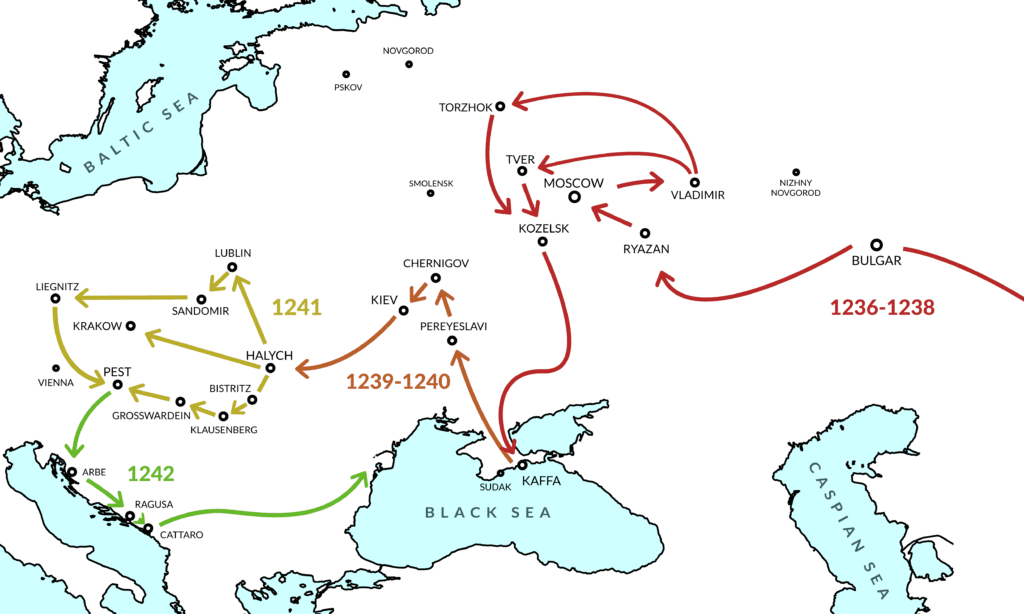

The Mongol Empire, forged by Genghis Khan in the early 13th century, was an unstoppable force that had already conquered vast territories across Asia. By the time of Genghis Khan’s death in 1227, his successors, particularly Ögedei Khan, sought to expand further westward. Under Ögedei’s leadership, Batu Khan was tasked with leading a campaign into Eastern Europe. This campaign began with the invasion of Volga Bulgaria and culminated in the conquest of Kievan Rus’ and other territories between 1237 and 1241.

The Mongols had already clashed with Rus’ forces years earlier at the Battle of Kalka River in 1223. Although this early encounter ended in a decisive Mongol victory, they temporarily retreated to focus on other conquests. However, their return in 1237 was far more organized and devastating.

The Campaign Begins: The Fall of Ryazan

In late 1237, Batu Khan’s forces crossed into Rus’ territory. Their first target was Ryazan, a principality southeast of modern Moscow. Envoys were sent to demand submission and tribute from Prince Yuri Igorevich of Ryazan. When these demands were refused, the Mongols laid siege to the city in December 1237. After six days of intense fighting, Ryazan fell. The city was utterly destroyed—its population massacred or enslaved—and it was not rebuilt.

The fall of Ryazan sent shockwaves across Rus’. News of the devastation spread rapidly, but the fragmented nature of Rus’ politics left its princes unable to mount a unified defense. Each principality faced the Mongols alone.

The Advance Through Vladimir-Suzdal

After Ryazan’s destruction, Batu Khan’s forces moved northwest toward Vladimir, one of the most powerful principalities in northeastern Rus’. On their way, they burned down Kolomna and Moscow in early 1238. Both cities offered little resistance and were quickly overwhelmed.

By February 1238, the Mongols reached Vladimir, the capital of Vladimir-Suzdal. Despite its fortifications and strategic importance, Vladimir fell after just three days of siege. The city was sacked and burned to the ground; its royal family perished in a fire within their cathedral. Grand Prince Yuri II fled northward to regroup.

The Battle of Sit River March 1238

By the time Yuri had gathered his troops and attempted to march southward toward Vladimir, it was too late—the city had already been sacked. Despite this setback, Yuri pressed on, determined to confront the invaders.

Yuri’s army was small and poorly equipped compared to the Mongol horde. He dispatched a reconnaissance force under a commander named Dorozh to locate the enemy. Dorozh returned with grim news: Yuri’s forces were already surrounded by Batu Khan’s troops. The Mongols, under the leadership of Subutai and Burundai, had expertly maneuvered their cavalry to cut off Yuri’s retreat.

Realizing his precarious position, Yuri attempted to organize his troops along the Sit River for a defensive stand. However, the Mongols launched a swift and devastating attack. Their superior mobility and coordination overwhelmed the Rus’ forces. The battle ended in a catastrophic defeat for Yuri’s army. Yuri himself was killed in combat alongside his nephew, Prince Vsevolod of Yaroslavl.

The defeat at the Sit River was more than just a military loss—it symbolized the end of unified resistance against the Mongols in Kievan Rus’. With Yuri’s death, no significant power remained to challenge Batu Khan’s dominance. The Mongols continued their campaign across Rus’, burning cities and subjugating local populations.

The Winter Campaign: A New Kind of Warfare

One remarkable aspect of the Mongol invasion was their ability to conduct military campaigns during winter—a season traditionally avoided by most armies due to logistical challenges. The frozen rivers and snow-covered landscapes became highways for the Mongols’ cavalry, allowing them to move swiftly across vast distances. This adaptability gave them a significant advantage over their enemies.

Their winter campaign continued through northeastern Rus’, where they razed towns such as Rostov and Yaroslavl. By spring 1238, much of northern Rus’ lay in ruins.

Novgorod and Pskov: The Exceptions

Despite their sweeping victories, not all regions fell to the Mongols during this campaign. Novgorod and Pskov were spared—likely due to their remote locations and harsh terrain that made them difficult targets for an exhausted Mongol army. Novgorod’s survival would later prove crucial for preserving elements of Rus’ culture and governance during this tumultuous period.

The Southern Campaign: Kiev and Beyond

After regrouping in 1239, Batu Khan resumed his campaign against southern Rus’. Chernigov fell first in autumn 1239 after a fierce battle. By December 1240, Batu’s forces reached Kiev—the spiritual and cultural heart of Kievan Rus’. Despite its historical significance and formidable defenses, Kiev succumbed after a prolonged siege. Contemporary accounts describe horrific scenes: thousands were killed or enslaved, and much of the city was reduced to rubble.

Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, an envoy from Pope Innocent IV who visited Kiev years later, described it as a ghost town littered with human remains. Once a thriving metropolis with tens of thousands of inhabitants, Kiev had been reduced to fewer than two hundred houses.

Impact on Rus’: The “Mongol Yoke”

The Mongol invasion marked the beginning of what Russian historians call the “Mongol Yoke,” a period lasting until 1480 when Russian principalities were under varying degrees of Mongol control. The conquered territories became part of the Golden Horde—a western extension of the Mongol Empire ruled by Batu Khan and his successors.

Under Mongol rule Russian princes were required to pay tribute (yasak) to their overlords and they had to seek approval from the khan for appointments or changes in leadership. Many cities never recovered from their destruction; others became shadows of their former selves. This period profoundly shaped Russian history. While it stifled economic development and cultural growth in some areas, it also centralized political power among surviving principalities like Moscow—setting the stage for future unification efforts under leaders like Ivan III.

European Reactions: Fear and Disunity

The devastation wrought by the Mongols did not go unnoticed in Western Europe. Reports from fleeing refugees painted a picture of an unstoppable horde advancing westward. Panic spread across European courts as rulers scrambled to prepare for an invasion that seemed inevitable.

In the spring of 1241, two pivotal battles unfolded that marked the westernmost extent of the Mongol Empire’s expansion into Europe, demonstrating the formidable military prowess of the Mongols and the vulnerability of European kingdoms to their tactics.

The Battle of Legnica

The Battle of Legnica, also known as the Battle of Liegnitz, took place in Silesia, near the town of Legnica in present-day Poland. A Mongol force, led by Baidar, Kadan, and Orda Khan, faced off against a combined European army under the command of Duke Henry II the Pious of Silesia. The European forces consisted of Polish and Moravian troops, supported by knights from various military orders, including the Teutonic Knights, Hospitallers, and Templars. This diverse coalition represented a united Christian front against the advancing Mongol threat.

The Mongols, employing their characteristic tactics of feigned retreat and divide-and-conquer, lured the European heavy cavalry away from the main body of infantry. Once isolated, the Mongol forces systematically defeated the knights, exploiting their superior mobility and archery skills.

The battle resulted in a decisive Mongol victory. Duke Henry II was killed in the fighting, his head paraded on a spear before the town of Legnica as a grim trophy of war. Estimates of European casualties vary widely, ranging from 2,000 to 40,000, effectively destroying the entire army. In the aftermath, the Mongols employed a macabre method of counting their fallen enemies, cutting off the right ear of each European casualty. Legend has it that they filled nine sackfuls with these grisly trophies.

The Battle of Mohi

Just two days after Legnica, an even larger confrontation took place at Mohi, near the Sajó River in Hungary. This battle pitted the main Mongol invasion force, led by Batu Khan and his brilliant general Subutai, against the army of King Béla IV of Hungary.

The Hungarian army, numbering around 100,000, initially outnumbered the Mongol force of about 80,000. However, the Mongols’ superior tactics and strategy would prove decisive.

Batu Khan initiated the battle with a frontal assault across the Sajó River, while Subutai maneuvered to outflank the Hungarian position. The Mongols employed innovative weapons, including catapult-fired explosives, to break through the Hungarian defenses.

As the battle progressed, the Mongols executed a masterful envelopment of the Hungarian army. Realizing they were about to be surrounded, the Hungarians attempted to retreat to their camp. Subutai seized this opportunity, bombarding the camp with explosives and unleashing his heavy cavalry.

The retreat quickly turned into a rout. King Béla IV narrowly escaped, fleeing to Croatia, while the majority of his army was decimated. Contemporary sources estimate Hungarian losses at around 60,000, effectively destroying the kingdom’s military might.

Aftermath

These twin victories at Legnica and Mohi demonstrated the Mongols’ military superiority and struck terror into the heart of Europe. The Mongols proceeded to ravage the Hungarian countryside for the next ten months, burning cities and massacring populations.

However, the Mongols’ further advance into Europe was halted by the death of the Great Khan Ögedei in December 1241. Batu Khan and his forces withdrew to participate in the selection of a new leader, inadvertently sparing much of Western Europe from invasion. This pause spared Western Europe from devastation.

Conclusion

The Mongol invasion of Russia in 1237 was not merely a military campaign — it was a cataclysmic event that reshaped Eastern Europe’s political landscape. It marked the beginning of centuries-long domination under the Golden Horde while leaving indelible scars on Russian society. The legacy of these invasions remains deeply embedded in Russian history — a testament to resilience amidst destruction and transformation born out of adversity.