The Danes hit London in 851 like a thunderclap: hundreds of longships clawing up the Thames, and within hours one of the richest trading emporia in England was stripped and burning. Then, just as quickly as they had come, the raiders slipped back to their ships, heavy with silver, slaves, and plunder.

London before the storm

In 851, “London” was not the dense, walled medieval city tourists picture today but a thriving riverside market known as Lundenwic, sprawled west of the old Roman walls along the Strand. Merchants from across the North Sea and the Frankish coast moored at its simple timber wharves, trading cloth, wine, pottery, hides, and slaves under the watchful eye of Mercian officials who taxed every deal.

The old Roman city, Lundenburh, with its stone walls and decaying gates, still loomed to the east like a sleeping giant, mostly abandoned but not forgotten. Power in the region was in Mercian hands: King Beorhtwulf claimed authority over London and its wealth, with the kings of Wessex watching closely from the south, eager to expand but wary of Mercia’s muscle.

The rise of the “summer hosts”

By the mid-ninth century, Viking raids on England had matured from quick coastal smash-and-grab attacks into more ambitious expeditions involving large fleets and deeper inland strikes. Chroniclers began to distinguish between small pirate bands and the larger “summer armies,” fleets gathered from many chieftains, willing to risk a whole campaigning season for a spectacular payoff.

These larger forces needed bigger prizes. Remote monasteries could be rich, but they could not match the concentrated wealth of a royal town like London: silver coin, imported goods, hostages for ransom, and possibly royal hoards. The Thames offered a perfect invasion highway: a wide, tidal river leading straight from the sea into the heart of Mercian territory, with few fixed defenses capable of stopping over three hundred longships once they committed to the ascent.

Three hundred and fifty ships in the Thames

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes 851 as the year it all escalated: some 350 Viking ships entered the Thames, an astonishing concentration of manpower and ambition. That number, even if a rough guess, suggests thousands of warriors – enough to overwhelm any single English army, especially if caught in the wrong place at the wrong time.

The fleet did not come solely for London. It represented an organized, multi-target campaign whose leaders knew exactly which towns promised the richest haul: first Canterbury in Kent, then London further upriver, both nodal points in Anglo-Saxon commerce and royal administration. Whether those leaders were Danish chieftains already experienced in English waters or ambitious newcomers seeking fame, the choice of targets suggests careful planning rather than random piracy.

Beorhtwulf’s disaster: Mercia routed

When the Danes pushed up the Thames, it fell to Mercian king Beorhtwulf to defend his most precious possession: London and its hinterland. The Chronicle states bluntly that the Danes put Beorhtwulf and his army to flight near London – a diplomatic way of saying the Mercian campaign collapsed in the face of the invaders.

That defeat mattered enormously. Mercia’s reputation as the old hegemon of southern England depended on military success and control of rich towns. To see its king beaten near London, then forced to abandon the town to sack and plunder, was both a practical and psychological catastrophe, signalling to friend and foe alike that Mercia could no longer guarantee security along the Thames.

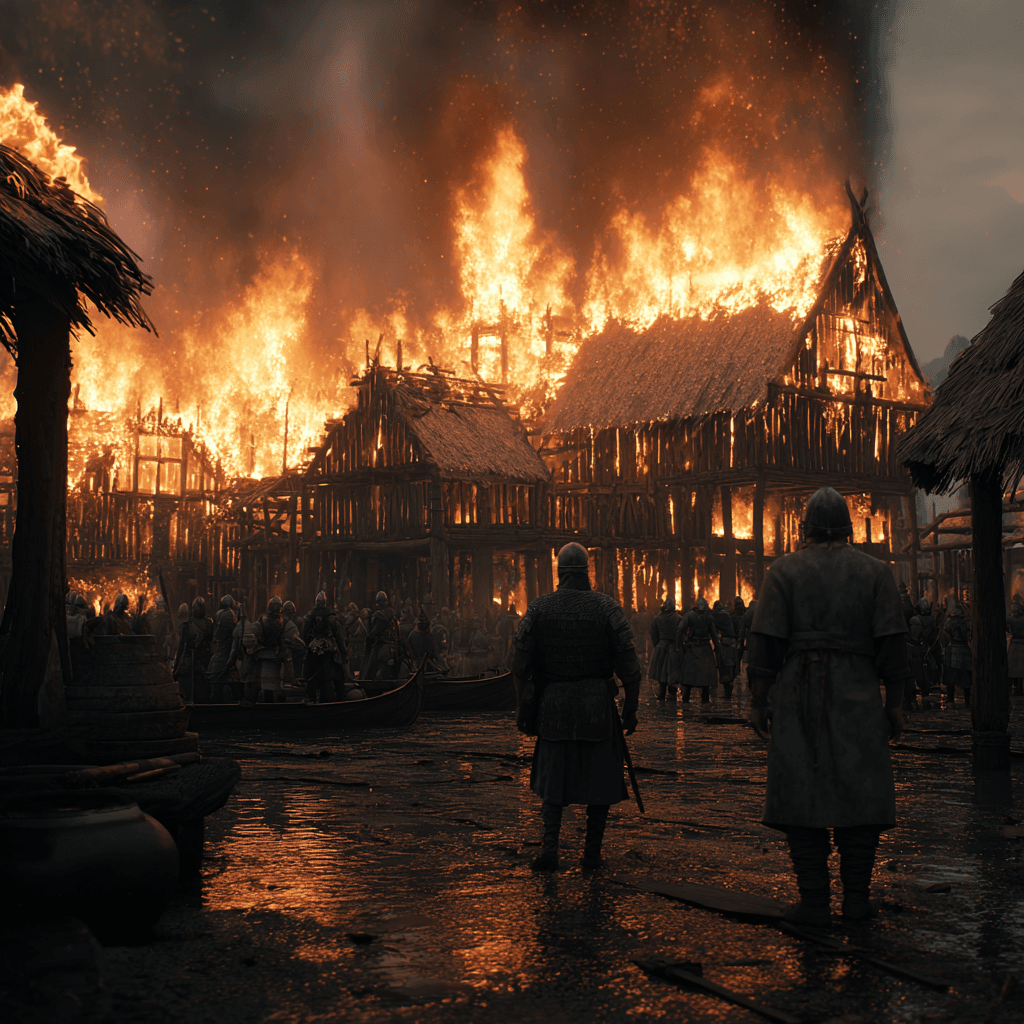

The sack of London: a trader’s nightmare

The Chronicle is brief, but the implications are stark: after routing Beorhtwulf, the Danes sacked London. Lundenwic was a township of wooden halls, booths, warehouses, and riverside infrastructure – all highly flammable, all deeply interwoven with trade networks stretching across the North Sea world. Flames racing down timber streets, warehouses kicked open and looted, merchants seized for ransom, coins and portable valuables swept up in sacks – this is what “sack” meant in practical terms.

For the Danes, the priorities were clear:

- Portable wealth: silver coins, hacksilver, weighing equipment, fine weapons, imported glass and pottery, and high-value textiles.

- People: captive merchants, craftsmen, and perhaps local elites could be ransomed or carried off to be sold as slaves abroad.

- Strategic destruction: burning storehouses, ships, and infrastructure made London less useful to enemies and more memorable as a terror lesson.

The assault likely hit not only the market but also the ecclesiastical and administrative symbols that anchored Mercian rule. Any church treasury, royal mint activity, or tax hoards in or near London would have drawn particular attention, turning a night of violence into a carefully curated economic shock.

From London to Canterbury and beyond

The fleet’s behaviour shows the logic of a mobile raiding force. After dealing with Mercia near London and plundering the town, the Danes moved on to sack Canterbury, another rich target tied to royal and ecclesiastical networks. By hitting both London and Canterbury in the same campaign, they struck at the prestige of Mercia and the spiritual prestige of Kent in one sweep.

Even more telling is what happened after those sacks. With their holds filling and resistance gathering, the Danes did not attempt to hold London, Canterbury, or any surrounding territory. Instead, they moved across the Thames into Surrey, where they eventually faced the West Saxon king Æthelwulf and his son Æthelbald at the battle of Aclea. The raiding arc – up the Thames, strike London, pivot to Canterbury, then head toward Wessex – reads like a calculated attempt to test all the major southern powers in a single campaign.

The “greatest slaughter” at Aclea

At Aclea (“Oak Field”), somewhere in Surrey, the momentum finally shifted. The West Saxon army met the Danish raiders and inflicted what the Chronicle calls the greatest slaughter of a heathen host yet heard of in England up to that time. The Danes who had so recently swaggered through London now found themselves encircled or pinned, their mobility blunted, their luck running out.

This victory mattered for Wessex’s reputation. While Mercia’s king had been driven off near London, Æthelwulf could now claim to have broken the very host that had humiliated his rival, killing large numbers of raiders and perhaps capturing or destroying ships. The battle did not end Viking incursions, but it set a narrative: Wessex, not Mercia, was the kingdom capable of delivering decisive blows to Scandinavian armies.

Why the Danes walked away instead of staying

Given the apparent ease with which they had taken London, why did the Danes not stay and build a permanent base there in 851? Several factors pushed them toward departure rather than settlement:

- Strategic timing: the mid-ninth century “summer hosts” still thought primarily in terms of seasonal campaigns, not of carved-out kingdoms. Holding a major town year-round would have required garrisons, supply lines, and political arrangements beyond the usual raiding playbook.

- Local resistance: once Beorhtwulf’s army was beaten, other forces could still assemble, as Wessex proved at Aclea. Any attempt to hold London long-term would have drawn combined resistance from multiple Anglo-Saxon rulers.

- Strategic options elsewhere: rich monasteries, coastal towns, and Frankish targets remained available around the North Sea, allowing raiders to keep roaming rather than becoming pinned down in one place.

So they did what professional raiders do when the ledger balances in their favor: they left. Their ships rode back down the Thames, heavily laden with plunder and prisoners, their leaders boasting of a campaign that had broken a king, sacked a major town, and still given them enough strength to contest Wessex before finally being checked.

London’s scars and recovery

Although the 851 raid devastated London, it did not destroy it permanently. Trade routes, geographic advantages, and royal interest encouraged recovery, just as other plundered towns across Europe rebuilt after Viking attacks. Over time, however, the very vulnerability of Lundenwic on the open riverside encouraged Anglo-Saxon rulers to rethink the city’s layout.

Later in the ninth century, evidence suggests that power shifted back toward the old Roman walled site, with rulers reoccupying and fortifying Lundenburh, the stone-walled city that would become medieval London. The burnings and sacks of earlier decades, including 851, made a powerful case for walls, gates, and planned defenses against repeat riverborne assaults.

A turning point for Mercia and Wessex

For Mercia, 851 sits on the downward slope. Once the dominant power in southern England, the kingdom now faced external humiliation and internal strain, eventually losing much of its autonomy under pressure from both Vikings and the rising house of Wessex. For Wessex, the Aclea victory that followed the sack became part of a story of resilience and gradual ascendancy, paving the way for Alfred and his successors to present themselves as the defenders of “all the English.”

The Danes, meanwhile, learned something too: that England, with its rich towns scattered along river networks and its fractious kings, offered one of the most lucrative hunting grounds in Europe. The night they sacked London and walked away loaded did not conclude the Viking story in England – it opened a new chapter.

The night that foreshadowed an era

Seen from the distance of centuries, the 851 sack of London reads less like an isolated disaster and more like a trailer for the decades to come. A great fleet pushing up the Thames, a king routed, a rich town stripped, and a victorious host slipping away with its spoils – these themes would repeat, on larger and larger scales, across the ninth and tenth centuries.

Yet this particular raid deserves attention because of the way it concentrates the drama: Mercia’s prestige, London’s prosperity, and Viking audacity all collide in one campaign. The Danes would be back in future generations, sometimes as raiders, sometimes as kings, but 851 marks one of the first moments when London learned, the hard way, that the Thames could carry ruin as easily as trade.