The Assassins became renowned for their unique approach to warfare and political influence. Rather than relying on large armies, they focused on the targeted assassination of political and religious leaders who opposed their cause.

The Assassins’ reputation for stealth and precision made them a feared force throughout the Middle East. Their ability to strike at the heart of enemy power structures gave them an influence far beyond their relatively small numbers. This reputation was further enhanced by tales of their seemingly supernatural abilities, such as appearing and disappearing at will.

Another of their strengths came from their religious fervour of these devout Shia Muslims. Their willingness to die for their cause, meant that assassination attempts against heavily guarded targets where there was little or no chance of the assassin escaping alive became possible.

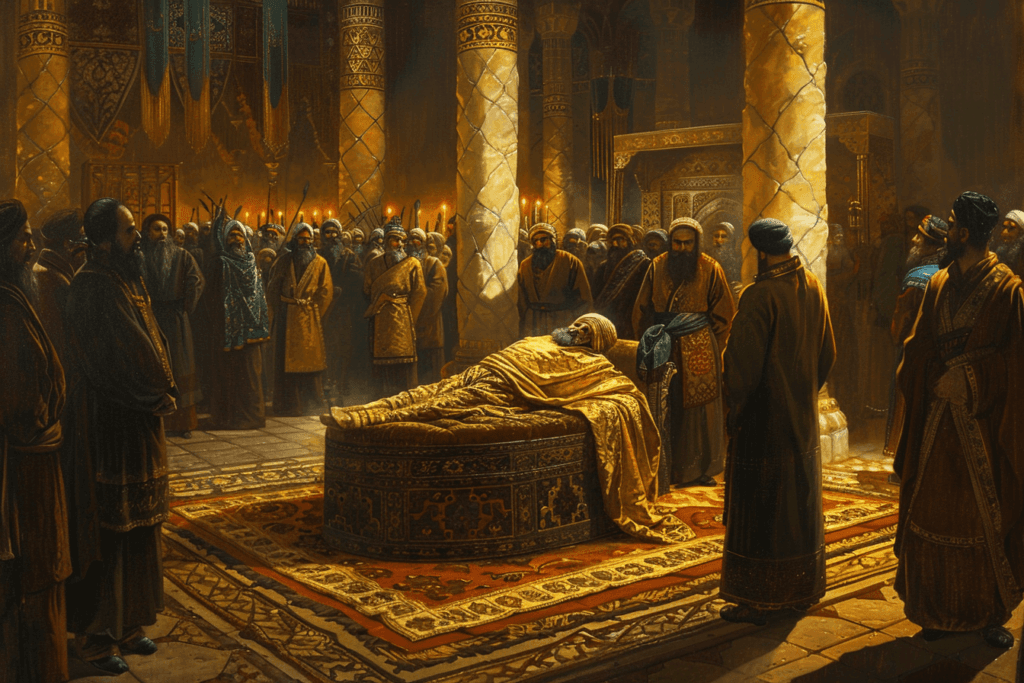

Nizam al-Mulk 1092

The first high-profile assassination of the sect came just two years after they had captured the fortress at Alamut. The assassination of Nizam al-Mulk, the powerful vizier of the Seljuk Empire, occurred on the evening of October 14, 1092 , not only ended the life of one of the greatest statesmen of the Islamic world but also set in motion a chain of events that would ultimately lead to the decline of the Sunni Seljuk Empire, the Assassins main enemy.

Nizam al-Mulk, was the most powerful man in the Seljuk Empire, second only to the Sultan himself. Under Nizam al-Mulk’s stewardship, the Seljuk Empire expanded its territories, strengthened its military, and became a center of cultural and intellectual growth. He was instrumental in establishing a network of madrasas, known as the Nizamiyyah, which spread Sunni Islamic learning throughout the empire, and earned him the enmity of the hardline Shia Muslim Assassins.

Nizam al-Mulk recognized the danger posed by the Assassins, and their propagation of the Shia faith, and advised Sultan Malik-Shah I to send an army against them. An expedition was launched under the command of Emir Arslantaş, but the siege of the assassins’ fortress at Alamut proved unsuccessful. This failure only served to embolden Hassan-i Sabbah and his followers.

The Night of the Assassination

In early October 1092, Sultan Malik-Shah I and his entourage, including Nizam al-Mulk, set out from the Seljuk capital of Isfahan for Baghdad, the seat of the Abbasid Caliph.

On the evening of October 14, 1092, as the royal procession neared the town of Nahavand, Nizam al-Mulk participated in the feast breaking the Ramadan fast in Sultan Malik-Shah’s tent. It was there, amid the flickering lanterns and murmuring attendants, that an assassin – disguised as a dervish – approached him. The assassin, later identified as Bu-Tahir, called out that he had a petition for the vizier’s consideration. As Nizam al-Mulk leaned out from his litter to receive the supposed petition, Bu-Tahir drew a dagger and plunged it into the vizier’s chest.

The attack was swift and perfectly timed. Nizam al-Mulk, already advanced in years, had no time to react. Blood poured from the wound as he collapsed. His guards rushed to his aid, but the assassin had already vanished into the night, leaving behind only chaos and confusion. Within moments, the empire had lost its greatest mind.

The Aftermath

News of the attack spread quickly through the camp. Sultan Malik-Shah I, upon hearing of the assassination attempt, rushed to Nizam al-Mulk’s tent. In a poignant moment, the Sultan sat by his dying vizier, reciting verses from the Quran into his ear. Nizam al-Mulk, the man who had guided the Seljuk Empire for nearly 30 years, passed away listening to these divine verses.

The immediate aftermath of Nizam al-Mulk’s death was one of shock and confusion. The Seljuk court, long accustomed to the vizier’s steady hand, found itself suddenly adrift. The assassination had not only removed a powerful political figure but had also exposed the deep rifts within the empire.

Then, within weeks, the Sultan too was dead – possibly poisoned, some say at the behest of the same factions that had arranged the vizier’s murder. The rapid demise of both ruler and vizier left the empire leaderless, plunging it into a succession crisis.

Janah ad-Dawla, Emir of Homs (1103)

Janah ad-Dawla had risen to prominence as the Governor of Homs and had become a key figure in Syrian politics. His influence extended far beyond the walls of his city, earning him the unofficial title of “the real governor of Syria”. Not only a skilled warrior, he was equally adept at diplomacy as he navigated the treacherous waters of regional politics, balancing relationships with both the Seljuk Turks and the newly arrived Crusaders.

While Janah ad-Dawla focused on external threats, a new and insidious force was taking root in the region: the Order of Assassins. The Assassins, driven by a complex mix of religious fervor and political ambition, had set their sights on expanding their influence beyond Persia into Syria. Their modus operandi was clear: strategic assassinations of key political and military leaders to sow chaos and advance their agenda.

The Fateful Day

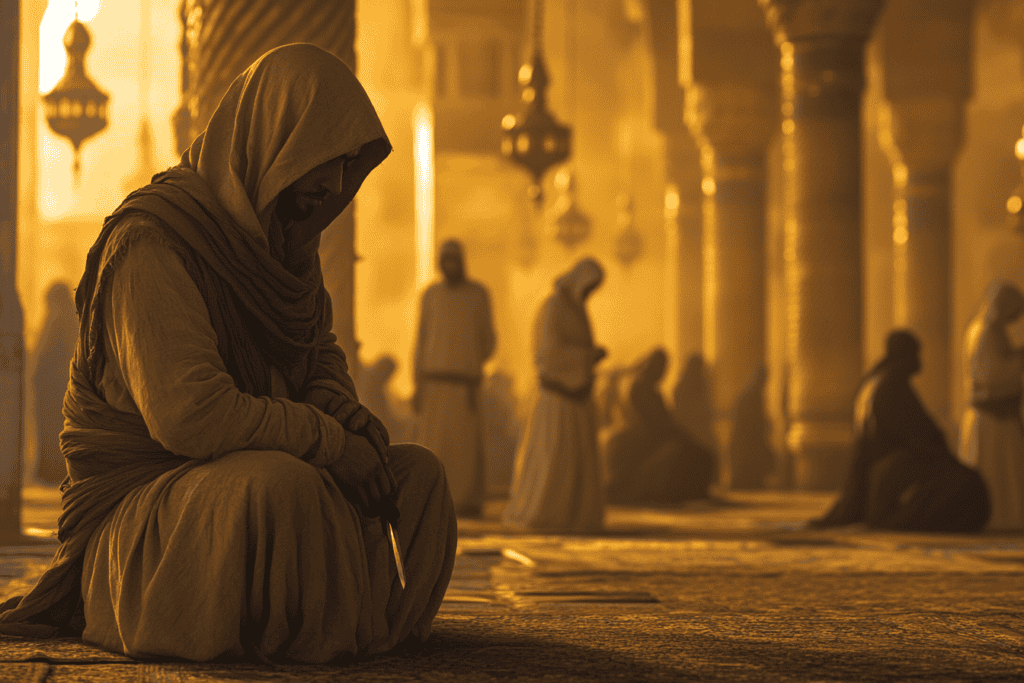

On May 1, 1103, Janah ad-Dawla’s life would come to a violent end in a manner that would become synonymous with the Assassins’ tactics. The emir had entered a mosque in Homs to perform his prayers, likely feeling secure within the sacred confines of the religious building.

Unbeknownst to Janah ad-Dawla and his guards, a group of Assassins had infiltrated the mosque, disguising themselves as devout worshippers. As the emir began his prayers, the assassins struck with deadly precision.

The attack was as swift as it was brutal. Multiple assailants converged on Janah ad-Dawla, their daggers flashing in the dim light of the mosque. The emir’s bodyguards, caught off guard by the sudden assault in such a holy place, scrambled to protect their lord.

What followed was a scene of utter chaos. The peaceful atmosphere of the mosque erupted into a frenzy of violence. Janah ad-Dawla’s bodyguards fought desperately against the assassins, their swords clashing in the sacred space.

The other worshippers, horrified by the bloodshed unfolding before them, fled in panic. Shouts and screams echoed through the mosque as the battle raged on. Despite their valiant efforts, Janah ad-Dawla’s protectors were overwhelmed by the well-prepared assassins.

In the end, the mosque floor ran red with blood. Janah ad-Dawla lay dead, along with several of his loyal bodyguards. Some of the assassins had also fallen in the melee, their bodies testament to the ferocity of the fight.

Aftermath and Implications

The assassination of Janah ad-Dawla sent shockwaves through the region. The loss of such a prominent figure created a power vacuum in Syria, destabilizing the delicate balance of power that had existed. This assassination marked the beginning of the Assassins’ expansion into Syria.

The killing also had broader implications for the ongoing struggle between the Muslim powers and the Crusader states. Janah ad-Dawla had been a key opponent of the Crusaders’ ally, the Seljuk ruler of Aleppo, so his death temporarily shifted the balance of power in favor of the Crusader-aligned factions.

Mawdud ibn Altuntash, the Governor of Mosul, in 1113

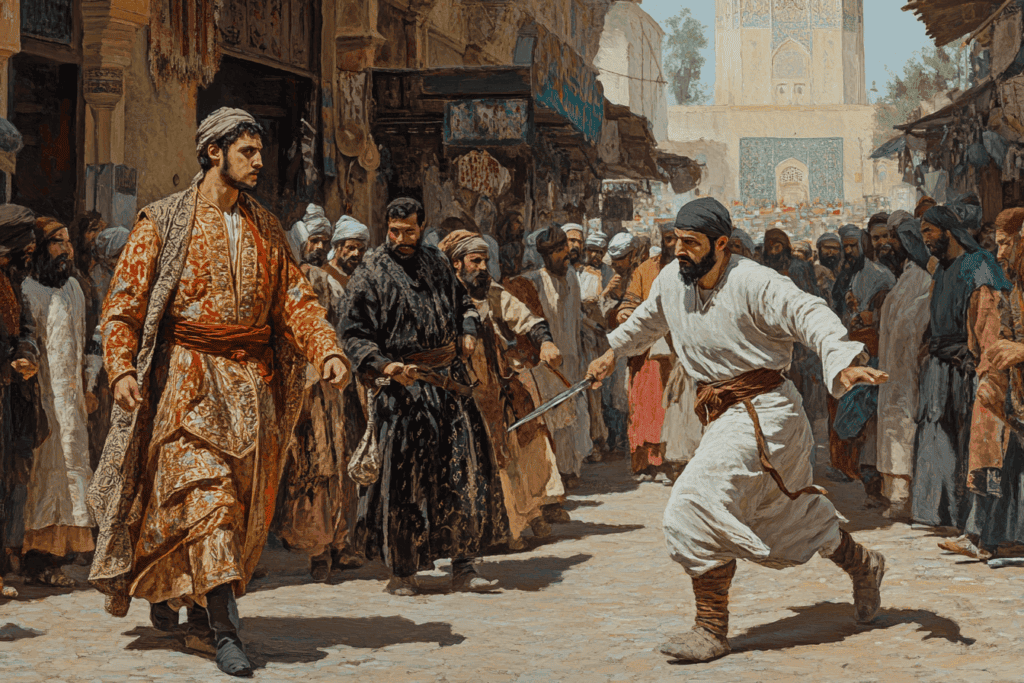

The assassination of Mawdud ibn Altuntash, the Governor of Mosul, in 1113 was a significant moment in the tumultuous history of the Crusades and the complex web of alliances and conflicts in the Middle East during the early 12th century. This shocking event unfolded in the bustling city of Damascus, where Mawdud had arrived as a guest of Toghtekin, the Governor of Damascus.

On that fateful day, October 2, 1113, Mawdud and Toghtekin had just finished their prayers and were returning from the mosque. The streets of Damascus are their usual hustle and bustle, with merchants hawking their wares and the scent of spices wafting through the air.

As Mawdud and Toghtekin walked side by side, engaged in conversation, a figure suddenly emerged from the crowd. Before anyone could react, the assailant lunged forward, brandishing a weapon. In a matter of seconds, Mawdud was struck four times, the blade finding its mark with deadly precision.

The attack was so swift and unexpected that Mawdud’s guards were caught off guard. As the Governor of Mosul collapsed to the ground, chaos erupted in the streets. People screamed and scattered, while Toghtekin’s men rushed to apprehend the assassin. In the ensuing melee, the killer was quickly overwhelmed and subdued.

Mawdud, gravely wounded, was hurriedly carried to a nearby house. As he lay there, his life ebbing away, those around him offered him food and water. However, Mawdud, ever the devout Muslim, refused to break his fast even in his final moments. This act of piety in the face of death speaks volumes about his character and devotion.

The assassin was identified as a member of the Order of Assassins, but who ordered the assassination?

Suspicion immediately fell on Toghtekin, Mawdud’s host in Damascus. The timing and location of the attack seemed too convenient to be mere coincidence. Toghtekin, however, vehemently denied any involvement. In a calculated move, he publicly accused Ridwan, the ruler of Aleppo, of orchestrating the assassination. A third suspect would be the Crusader States as Mawdud had been a key figure in the fight against them.

The assassin, who had been captured alive, was subjected to a brutal public execution. In a grim spectacle that served as both punishment and warning, the killer was beheaded, and his body was burned in the streets of Damascus.

Taj al-Mulk Buri, Governor of Damascus (1132)

Buri had earned the enmity of the Assassins through his actions against their sect in Damascus. In 1129, following the death of his father Toghtekin, Buri had launched a brutal crackdown on the Assassins in the city. This purge, supported by his military commander Yusuf ibn Firuz, had resulted in a massacre of Ismaili adherents. The streets of Damascus had run red with blood as “dogs yelp[ed] and quarrel[ed] over their limbs and corpses”.

The scale of this slaughter was staggering, with at least 6,000 members of the Assassins community reported to have been killed. Those who survived the initial onslaught were forced to flee to Frankish territories, effectively destroying the Assassins’ power base in Damascus.

This devastating blow to the Assassins’ Syrian mission could not go unanswered.

On a warm spring day in May 1132, the streets of Damascus bustled with the usual activity of a thriving medieval city. Taj al-Mulk Buri, the powerful Governor who had ruled Damascus since 1128, went about his daily affairs, unaware of the danger that lurked in the shadows.

As Buri made his way through the city, two figures emerged from the crowd. These men, their identities concealed, were highly trained Assassins. In a swift and brutal attack, the Assassins struck, plunging their daggers into Buri’s stomach. The Governor’s guards, caught off guard by the suddenness of the assault, quickly rallied to defend their lord. In the ensuing chaos, the Assassins were cut down, “hacked to pieces” by Buri’s loyal protectors. However, the damage had been done, Taj al-Mulk Buri had been gravely wounded.

Buri did not succumb immediately to his wounds, for thirteen long months, the once-mighty Governor of Damascus fought against the festering stomach wounds inflicted by his would-be killers. During this time, the political landscape of Damascus and the surrounding regions was thrown into turmoil. Buri’s incapacitation and eventual death, left a power vacuum that various factions sought to exploit.

Abbasid caliphs al-Mustarshid (1135) and ar-Rashid (1138)

The circumstances surrounding al-Mustarshid’s death are shrouded in mystery and controversy. On the 29th August 1135 CE, the caliph was found murdered in his tent while reading the Quran.

Following the shocking assassination of al-Mustarshid, his son al-Rashid ascended to the caliphate in 1135. His reign, however, would be tragically short-lived. Just three years after his father’s death, al-Rashid himself fell victim to the Assassins’ blades in 1138.

The consecutive murders of father and son, both holding the highest religious and political office in Sunni Islam, sent shockwaves through the Islamic world. These assassinations demonstrated the reach and audacity of the Assassins, who seemed capable of striking at the very heart of power with impunity.

To this point, all of the Assassins’ major victims had been Sunni Muslims – the implacable enemies of the fervent Shia Muslim Order of the Assassins. However, 14 years later they claimed their first high-profile Christian victim.

Raymond II, Count of Tripoli, 1152

Raymond II, born around 1116, ascended to the position of Count of Tripoli in 1137 following the death of his father, Pons. As Raymond’s reign progressed, he found himself embroiled in various conflicts and controversies that would ultimately contribute to his downfall.

Raymond’s personal life was far from peaceful. His marriage to Hodierna of Jerusalem was notoriously unhappy, to the point where Queen Melisende of Jerusalem, Hodierna’s sister, had to intervene to mediate their conflicts. This familial strife not only affected Raymond’s personal life but also had implications for the political alliances between Tripoli and Jerusalem.

The Fateful Day

The events leading to Raymond’s assassination unfolded against this backdrop of tension and mistrust. On that fateful day in 1152, Raymond found himself at the center of a carefully orchestrated plot.

The day began with what seemed like a gesture of reconciliation. Queen Melisende of Jerusalem had come to Tripoli to mediate the ongoing conflict between Raymond and his wife, Hodierna. As the visit concluded, Hodierna decided to leave Tripoli for Jerusalem with her sister. Raymond, in an act of chivalry or perhaps political necessity, chose to escort the women for a short distance outside the city.

As Raymond made his way back to Tripoli, likely with a reduced escort after seeing off the royal women, he approached the southern gate of the town. It was here that a group of Assassins lay in wait, having carefully planned their attack.

The Assassins, known for their meticulous planning and fearless execution, struck with precision. Armed with daggers, they ambushed Raymond, catching him and his remaining guards by surprise. The attack was swift and deadly, with multiple assailants ensuring that their target had no chance of escape.

The Aftermath

News of the Count’s assassination spread quickly through Tripoli and beyond. The first Christian ruler to fall victim to the Assassins, Raymond’s death sent shockwaves through the Crusader states. It demonstrated the reach and audacity of the Assassins, being carried out in a public place, with the killers showing no regard for their own safety or escape. This brazen approach was designed not just to eliminate a target but to send a message and instill fear in others

Some speculate that it was a response to Raymond’s encroachment on the independence of the Assassins’ statelet on the Syrian coast. Others suggest it may have been related to broader political machinations in the region, possibly involving rival Crusader factions or Muslim powers seeking to destabilize the County of Tripoli.

Raymond’s death left the County of Tripoli in a precarious position. He was succeeded by his son, Raymond III, who was still a minor at the time. This transition of power to a child ruler opened the door for increased influence from the Kingdom of Jerusalem and other neighboring states in Tripolitan affairs.

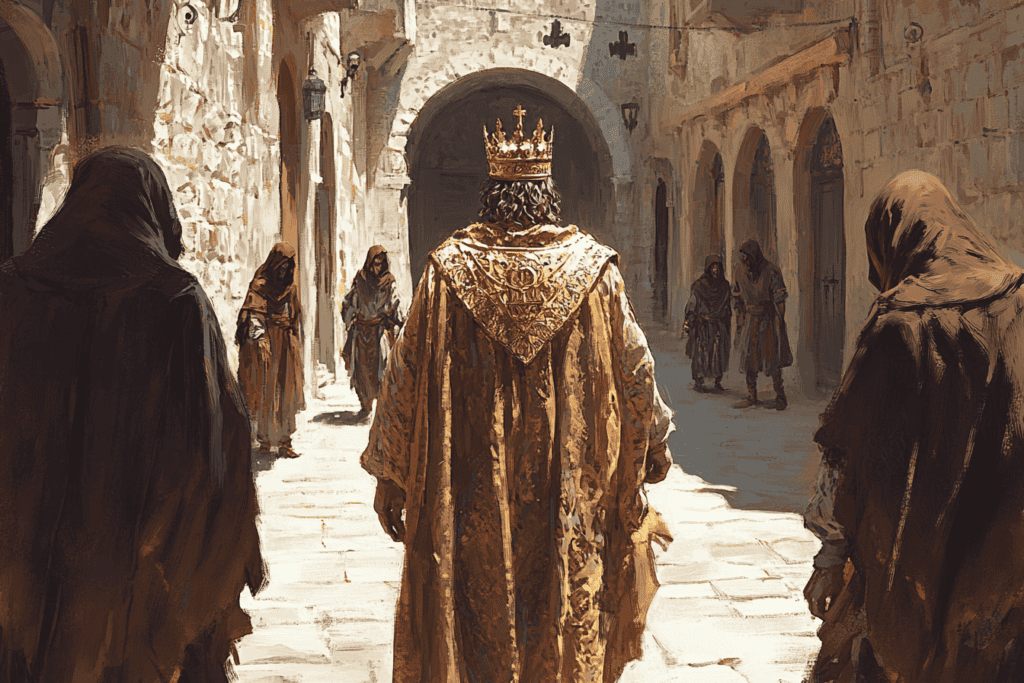

Conrad of Montferrat, the de facto King of Jerusalem, 1192.

The assassination of Conrad of Montferrat, the de facto King of Jerusalem, on April 28, 1192, stands as one of the most intriguing and controversial events of the Crusader era. This medieval murder mystery, set against the backdrop of the Third Crusade, involves a cast of characters that reads like a who’s who of 12th-century power players in the Holy Land.

The Rise of Conrad

Conrad of Montferrat, an Italian nobleman from Piedmont, had arrived in the Holy Land in 1187, at a time when the Kingdom of Jerusalem was in crisis. Saladin’s forces had recently captured Jerusalem, and the Christian presence in the Levant was hanging by a thread. Conrad’s military acumen and political savvy quickly made him a key figure in the defense of what remained of the Crusader states.

His most significant achievement came when he successfully defended the coastal city of Tyre against Saladin’s siege. This victory not only preserved a crucial foothold for the Christians but also established Conrad as a formidable leader. His influence grew further when he married Isabella I of Jerusalem in November 1190, effectively making him the de facto ruler of the kingdom.

Political Tensions

As the Third Crusade progressed, tensions arose between Conrad and other prominent figures, particularly Richard I of England, known as the Lionheart. Richard initially supported Guy of Lusignan’s claim to the throne of Jerusalem, creating a rift with Conrad and his supporters.

The political landscape shifted in April 1192 when the barons of the Kingdom of Jerusalem unanimously elected Conrad as their king. This decision, much to Richard’s consternation, set the stage for what would become a tragic turn of events.

The Fateful Day

On April 28, 1192, just days after his election and before he could be crowned, Conrad’s life came to a violent end on the streets of Tyre. The events of that day have been recounted by various chroniclers, both Christian and Muslim, with slight variations in the details.

Conrad had been dining with Philip, the Bishop of Beauvais, a kinsman and friend. As he made his way home, two assassins approached him. These men, who had reportedly been in Conrad’s entourage for months, possibly disguised as monks or servants, struck with deadly precision.

The attack was swift and brutal. The assassins stabbed Conrad multiple times in the side and back. In the chaos that ensued, one of the attackers was killed on the spot by Conrad’s guards, while the other was captured after seeking refuge in a nearby church.

The Aftermath

The immediate aftermath of the assassination was one of shock and confusion. Conrad’s pregnant wife, Isabella, was left widowed, and the kingdom was suddenly without its newly elected ruler. Some accounts suggest that Conrad lived long enough to receive last rites, though the veracity of these deathbed scenes is debated by historians.

The captured assassin was interrogated, though accounts differ on what information, if any, was extracted before his execution. He was eventually dragged through the streets of Tyr and executed.

The assassination of Conrad of Montferrat sparked immediate speculation about who might have orchestrated the attack. The killers were identified as members of the Order of Assassins. While they were the direct perpetrators, many believed they acted on behalf of a more powerful patron. But who? We are unlikely to ever know.

Read Part 1 to discover the origins of the Assassins and their Eagles Nest lair!