Prologue: The Rhine Frontier

The Roman Empire in the early 5th century CE was a shadow of its former glory. Once an unassailable superpower, the empire had been weakened by internal strife, economic instability, and relentless external pressures. Nowhere was this fragility more evident than along the Rhine frontier. This border, separating Roman Gaul from the barbarian lands to the north and east, had been a critical line of defense for centuries. Yet by the dawn of the 5th century, it was increasingly vulnerable to incursions from restless tribes seeking better lands and opportunities.

The Rhine was not merely a physical boundary but a cultural and political fault line. On the Roman side were cities, fortified camps, and a network of roads that ensured trade and military mobilization. On the other side lay the forests and rivers of Germania, home to a mosaic of tribes – Franks, Vandals, Alans, Burgundians, and others – each with its own ambitions and rivalries. For centuries, the Rhine had held firm as a bulwark against barbarian advances, but the winter of 406 CE would see this delicate balance shattered.

The Migration Crisis

The origins of the crisis that culminated in the Battle of Mainz can be traced to the east, far beyond the Danube and Rhine frontiers. The late 4th century had witnessed the westward migration of the Huns, a nomadic people whose arrival disrupted the equilibrium of the barbarian world. Tribes such as the Goths, Vandals, and Alans found themselves pressured to move, either seeking refuge within the Roman Empire or carving out new territories at its expense. These migrations created a domino effect, displacing groups and inflaming tensions across Europe.

By 405 CE, the situation had reached a boiling point. A coalition of Vandals, Alans, and Suebi – each motivated by a mix of desperation and opportunism – had gathered along the Rhine frontier. This was no ordinary raiding party but a mass migration of tens of thousands, including warriors, women, children, and elderly. The Rhine, frozen solid in the bitter winter of late 406, offered them a rare opportunity to cross en masse into Roman territory.

The Roman Response

The Roman Empire was ill-prepared to meet this threat. Decades of civil war and economic decline had hollowed out the once-mighty legions. Moreover, the political situation in 406 was chaotic. The Western Empire, nominally ruled by Emperor Honorius from his court in Ravenna, was effectively controlled by his generalissimo, Stilicho. While Stilicho was a capable commander, his resources were stretched thin. His focus was primarily on the Italian heartland and the Gothic threat led by Alaric to the south.

The Rhine frontier, garrisoned by underfunded and undermanned forces, was left dangerously exposed. Local commanders, such as those stationed in Mainz, faced the daunting task of holding back a vast barbarian horde with limited resources. Appeals for reinforcements went unanswered, as Stilicho prioritized other crises.

The Battle Unfolds

In late December 406 CE, the barbarian coalition began its fateful crossing of the frozen Rhine near Mainz. The Vandals, led by King Godigisel, formed the core of the force. Accompanying them were the Alans, a nomadic people skilled in mounted warfare, under their leader Respendial, and the Suebi, a smaller but equally determined group.

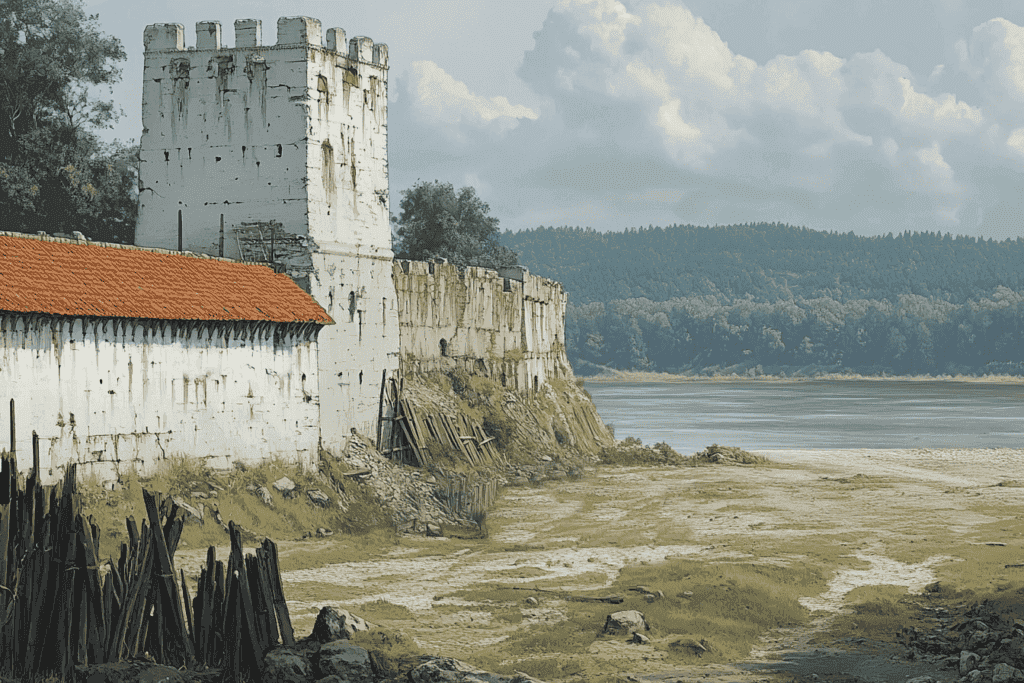

The defenders of Mainz, led by Roman provincial commanders whose names have been lost to history, rallied their forces for a desperate defense. Mainz, an important Roman city and military base, was both a strategic prize and a critical obstacle to the barbarian advance. The city’s walls and garrison were formidable but not impregnable, especially against an enemy of this magnitude.

The battle began with skirmishes along the frozen river. Roman archers and artillery stationed on the walls of Mainz unleashed volleys against the advancing barbarians, attempting to disrupt their crossing. Despite these efforts, the sheer numbers of the coalition overwhelmed the defenders. Thousands of warriors, clad in furs and chainmail, stormed across the ice, their war cries echoing across the frozen expanse.

As the barbarians reached the Roman side, the battle descended into brutal close-quarters combat. The Roman defenders, outnumbered but disciplined, fought valiantly. Roman infantry formations held firm initially, their shields and swords creating a wall of resistance. However, the barbarians’ persistence, coupled with their greater numbers, began to take its toll.

A critical moment came when King Godigisel, leading the Vandal charge, was struck down in the melee. The death of their leader momentarily threw the Vandals into disarray, and the Romans surged forward, sensing an opportunity to rout their enemies. However, Respendial, the Alan leader, quickly took command, rallying the coalition with a decisive counterattack. The Alans’ mounted warriors, despite the icy terrain, proved instrumental in turning the tide. Their mobility and ferocity broke through Roman lines, sowing chaos among the defenders.

As night fell, the Roman forces were overwhelmed. The walls of Mainz were breached, and the city was subjected to pillage. Survivors among the Roman garrison and civilian population either fled or were captured. The barbarians, now firmly entrenched on the Roman side of the Rhine, celebrated their hard-won victory.

Aftermath: A New Order

The consequences of the Battle of Mainz were profound and far-reaching. The defeat marked the collapse of Roman control over the Rhine frontier. With no effective resistance in their path, the Vandals, Alans, and Suebi fanned out into Roman Gaul. Their advance unleashed a wave of destruction and displacement, as towns and cities were sacked, and local populations were uprooted.

For the Vandals, the battle marked a turning point in their history. Despite the loss of King Godigisel, his son Gunderic assumed leadership and guided the tribe on its continued migration. Within a few decades, the Vandals would cross into Spain and eventually North Africa, where they established a kingdom that would become a major power in the Western Mediterranean.

The Alans, too, left their mark. Though initially integrated into the coalition, they would eventually splinter, with some groups settling in Spain and others joining Roman service as foederati (allied troops). The Suebi carved out a kingdom in northwest Iberia that endured for centuries.

For the Roman Empire, the loss of Mainz and the events that followed were symptomatic of its declining ability to control its frontiers. The empire’s inability to respond effectively to the barbarian incursions of 406 CE hastened the fragmentation of its western provinces. Within seventy years, the Western Roman Empire would cease to exist.

Legacy: The Turning of an Era

The Battle of Mainz is often overshadowed by other events of Late Antiquity, such as the Sack of Rome in 410 CE or the deposition of Romulus Augustulus in 476 CE. Yet it represents a pivotal moment in the broader narrative of the empire’s decline and transformation. The crossing of the Rhine in 406 CE was not merely a military defeat but a seismic shift in the demographic and political landscape of Western Europe.

What is clear is that the events of 406 CE set the stage for a new chapter in European history. The migrations and conquests that followed laid the foundations for the medieval kingdoms of Gaul, Spain, and beyond. The Vandals, Alans, and Suebi, once peripheral players in the Roman world, emerged as central actors in the post-Roman order.