The Road to Constantinople

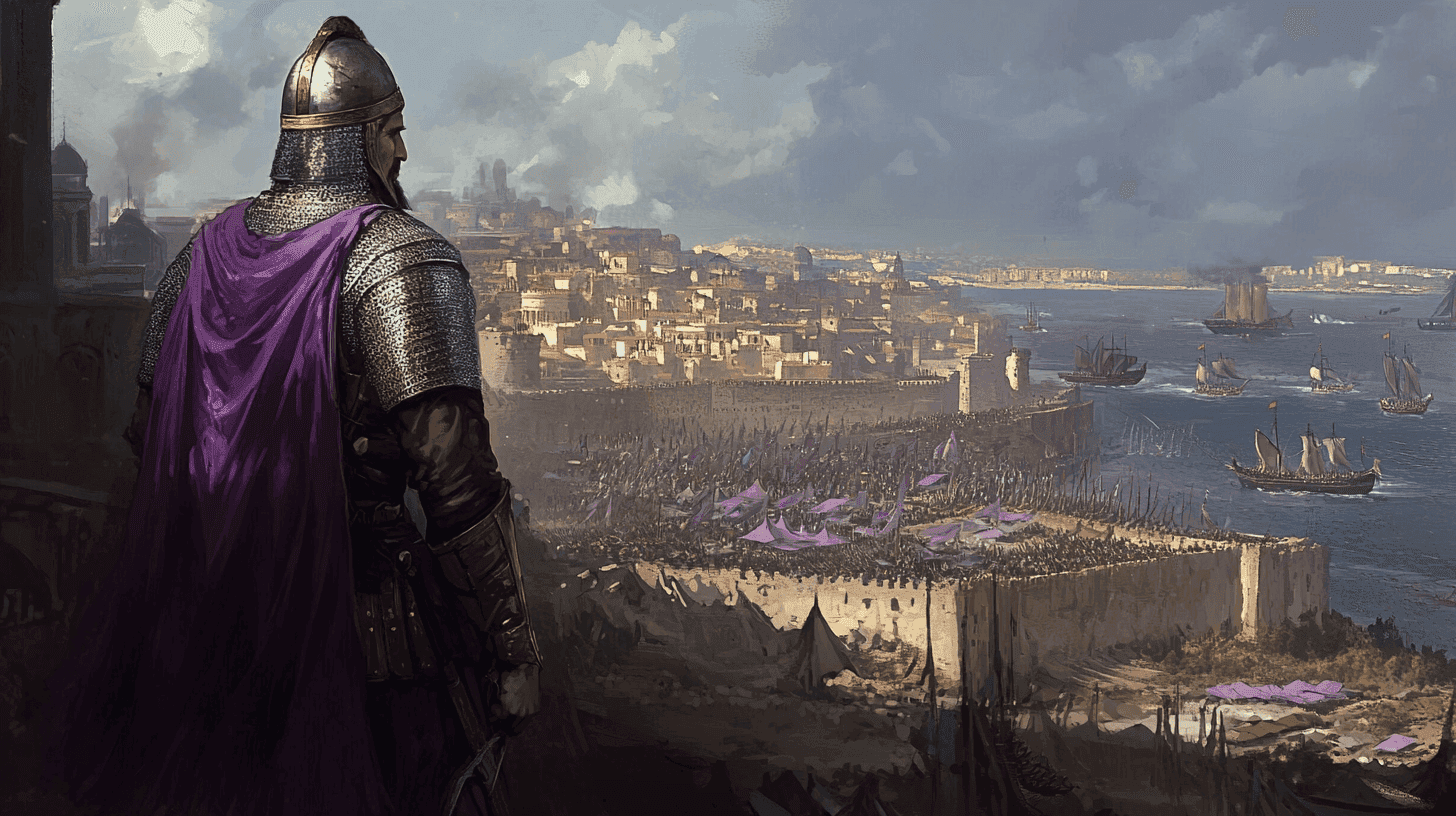

In the early 8th century, the Muslim Umayyad Caliphate was at the height of its power, having expanded rapidly across North Africa and into the Iberian Peninsula. The Byzantine Empire, heir to the Roman legacy, stood as the primary obstacle to Umayyad expansion into Europe from the east. After years of preparation and smaller incursions, the Umayyads launched their most ambitious campaign yet: the conquest of Constantinople itself.

The Umayyad forces were led by Maslama ibn Abd al-Malik, brother of Caliph Umar II. This massive expedition comprised both land and sea components, showcasing the Caliphate’s immense resources and determination. An army estimated at 80,000 strong marched overland through Asia Minor, while a fleet of approximately 1,800 ships sailed to support the siege.

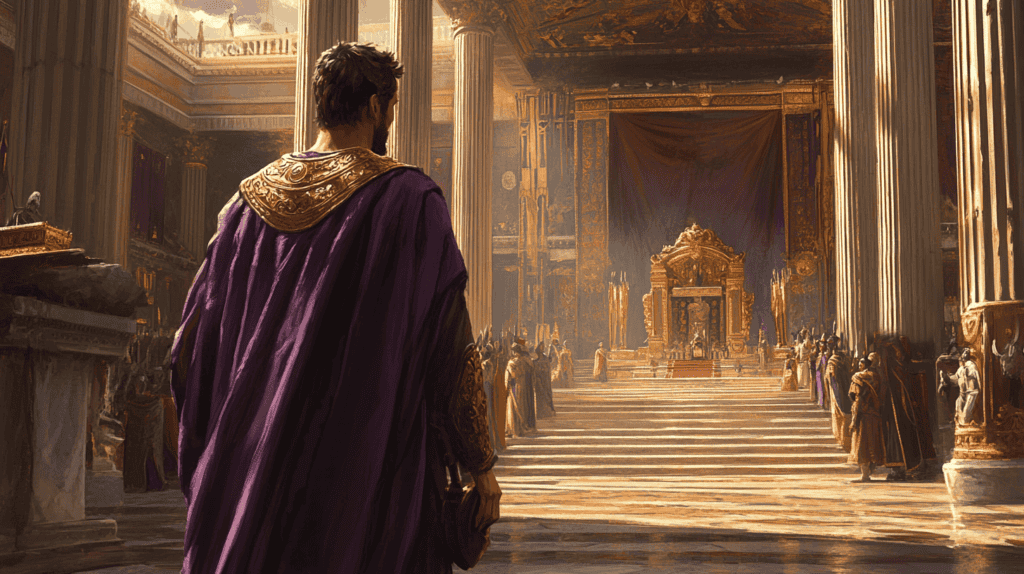

The Byzantine Empire on the Brink

As the Umayyad forces approached, the Byzantine Empire found itself in a precarious position. Years of internal strife had weakened the state, and the threat of civil war loomed. In this tumultuous environment, a skilled military commander named Leo III the Isaurian emerged as a pivotal figure.

Leo, recognizing the gravity of the situation, employed clever diplomacy to secure his position. He initially feigned alliance with the advancing Arabs, promising to recognize the Caliph’s suzerainty. This deception allowed him to enter Constantinople and seize the imperial throne on March 25, 717, just months before the siege began.

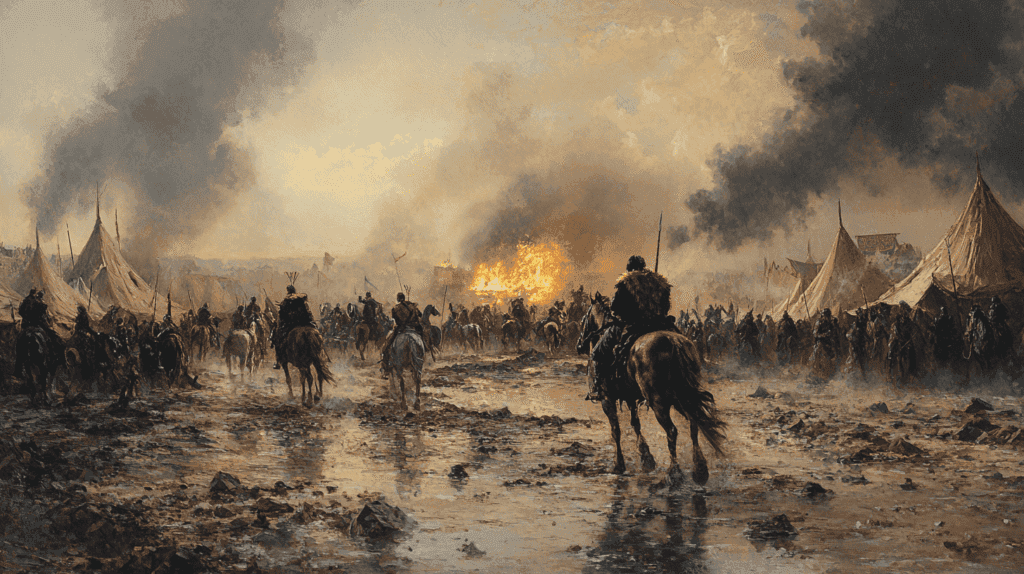

The Siege Begins

On August 15, 717, the residents of Constantinople awoke to find their city surrounded by the massive Umayyad force. Maslama ordered his men to construct elaborate siege works, including trenches and a stone wall to counter the city’s formidable land defenses.

The Byzantine response was swift and well-prepared. Leo III, an experienced soldier, had strengthened the city’s defenses and stockpiled supplies in anticipation of a prolonged siege. He ordered all civilians without three years’ worth of provisions to evacuate, ensuring that the remaining population could withstand an extended blockade.

Naval Warfare and Greek Fire

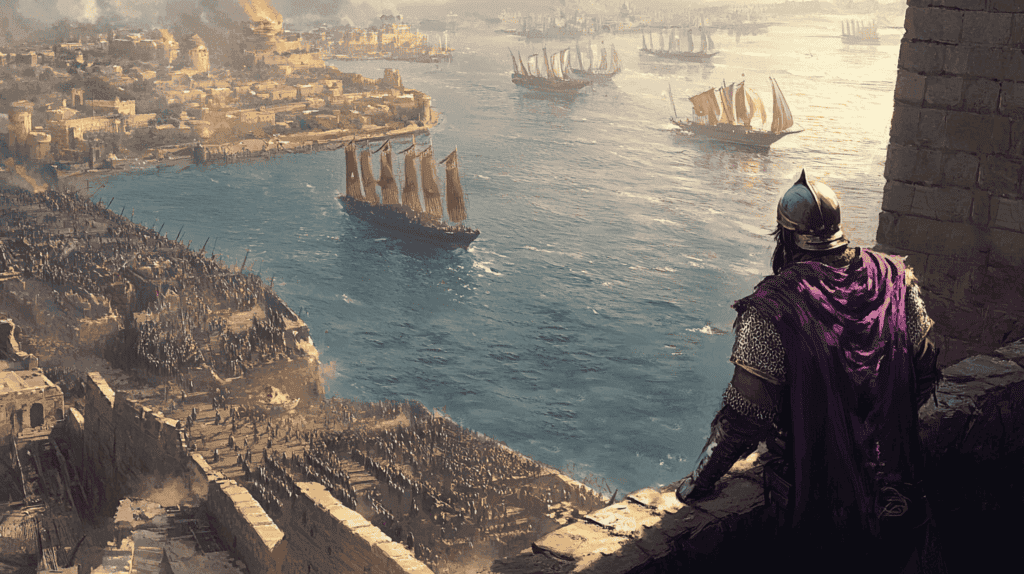

The naval aspect of the siege proved crucial from the outset. On September 1, 717, the Muslim fleet of 1,800 ships arrived in the Sea of Marmara, presenting a formidable sight. Two days later, on September 3, Sulayman made a bold move, leading his fleet into the Bosphorus strait. This formidable armada aimed to complete the blockade of Constantinople by sea, cutting off the city’s vital supply lines.

As the Arab fleet maneuvered into position, it split into several squadrons. Some vessels sailed south of Chalcedon to guard the southern entrance of the Bosphorus, while others moved further into the strait, establishing positions between Galata and Kleidion. This strategic deployment was designed to sever Constantinople’s communication with the Black Sea, a critical lifeline for the Byzantine capital.

However, the Arabs’ lack of experience in these treacherous waters soon became apparent. As the rearguard of the Arab fleet, consisting of twenty heavy ships carrying 2,000 marines, attempted to pass the city, they encountered a sudden change in wind direction. The southerly wind that had been propelling them forward abruptly stopped and then reversed, leaving the ships drifting helplessly towards the city walls.

Emperor Leo III, a skilled military tactician, seized this moment of vulnerability. He launched a surprise attack using the Byzantine navy, which had been hiding in the Golden Horn. The Byzantine ships were armed with a secret weapon that would prove decisive in this encounter – Greek Fire.

Greek Fire was a highly flammable liquid that could continue burning even on water. Launched through siphons, it struck terror into enemy sailors and was particularly effective against wooden ships. As the Byzantine vessels engaged the drifting Arab ships, they unleashed this terrifying weapon.

The results were devastating for the Arab fleet. Theophanes reported that some ships went down with all hands, while others, engulfed in flames, drifted helplessly down to the Princes’ Islands. The Byzantine victory was decisive.

The Arab fleet’s inability to establish naval superiority would prove crucial in the months to come, allowing Constantinople to maintain its sea-based supply lines.

The Brutal Winter of 717-718

As autumn turned to winter, the siege settled into a war of attrition. The winter of 717-718 proved to be exceptionally harsh, described by chroniclers as “the cruelest winter that anyone could remember”. This severe weather played a decisive role in the outcome of the siege.

While Constantinople, supplied via the Black Sea, managed to endure the winter without severe hardship, the besieging Arab forces faced catastrophic conditions. Disease and starvation ravaged their ranks. The situation became so dire that the Arab soldiers were forced to eat their camels, horses, and donkeys. Some reports even suggest they resorted to consuming small rocks and the bodies of their dead comrades.

The ground remained frozen for an astonishing 100 days, and the Arabs had no choice but to dispose of their numerous dead by casting them into the Sea of Marmara. This grim scene must have had a profound impact on morale, as the once-mighty army found itself at the mercy of nature and Byzantine resilience.

Bulgarian Intervention and Arab Setbacks

As spring approached, the tide began to turn decisively against the Umayyad forces. A key factor in this shift was the intervention of the Bulgars, who had established friendly relations with the Byzantines a year earlier under Khan Tervel.

The Arab army, already weakened by the brutal winter and constant attrition of siege warfare, was caught off guard by the Bulgarian attack on their rear in July 718. Contemporary chroniclers report staggering losses, with at least 30,000 Arab soldiers falling in the initial Bulgar assault. This unexpected threat forced the Arabs to divide their attention, constructing additional defensive works to protect against Bulgarian raids.

Simultaneously, Leo III capitalized on the Arabs’ weakened state by launching sorties from the city. Although these attacks were generally repelled at the Arab trenches, they further sapped the besiegers’ strength and morale.

The Final Blow: Naval Defeats and Retreat

The Arab hopes for reinforcement and resupply were dashed in the spring of 718. Two separate Arab fleets, sent to bolster the besieging forces, met with disaster. In a stunning turn of events, many of the Christian crews manning these ships defected to the Byzantine side, providing Leo III with crucial intelligence and additional naval strength.

Armed with this information, the Byzantine navy was able to intercept and destroy these reinforcement fleets. This naval victory not only prevented the Arabs from receiving much-needed supplies and manpower but also demonstrated the waning loyalty within the Caliphate’s forces.

On land, an additional Arab army sent to reinforce the siege met a similar fate. As it marched through Asia Minor, this force was ambushed and decisively defeated by Byzantine forces, likely employing intelligence gained from the naval defectors.

The Siege is Lifted

Faced with mounting losses, dwindling supplies, and attacks from multiple directions, the Arab forces found their position untenable. On August 15, 718, exactly one year after the siege began, Maslama made the difficult decision to lift the siege and retreat.

The withdrawal quickly turned into a disaster for the Umayyad forces. As the remnants of the once-mighty Arab fleet attempted to return home, it encountered violent storms in the Aegean Sea. Already weakened by months of conflict and the loss of experienced crews to defection, many ships were lost to the tempestuous waters.

The Byzantine fleet, emboldened by its earlier successes, harried the retreating Arabs. Employing Greek Fire and superior naval tactics, they inflicted further heavy losses on the demoralized Muslim forces.

Aftermath and Historical Significance

For Byzantium, the victory represented a stunning reversal of fortunes. Leo III, who had seized power just before the siege, was now hailed as a savior of Christendom. His successful defense of Constantinople legitimized his rule and ushered in the Isaurian dynasty, which would govern the empire for nearly a century. This period of stability allowed Byzantium to regain its strength and reassert its influence in the Mediterranean world.

For the Umayyad Caliphate, the failed siege marked the high-water mark of their expansion into Byzantine territory. The massive losses in manpower and resources dealt a severe blow to Umayyad prestige and military might. This defeat, combined with other setbacks such as the Battle of Tours in 732 CE, effectively ended the period of rapid Muslim expansion that had characterized the early Islamic conquests.