In the year 866 CE, a dramatic and transformative chapter in English history unfolded as the Vikings captured the city of York and established their own kingdom in Northumbria. This event marked not only a significant milestone in the Viking Age but also a turning point in the cultural, political, and economic landscape of medieval England. The establishment of the Viking Kingdom of York, or Jorvik, was part of a larger wave of Norse invasions and settlements that reshaped the British Isles during the early medieval period.

Background: The Great Heathen Army

The Viking conquest of York was spearheaded by a formidable coalition of Scandinavian warriors known as the Great Heathen Army. Unlike earlier Viking raids that focused on plundering monasteries and coastal settlements, this invasion marked a shift in strategy. The Great Heathen Army, which landed in East Anglia in 865 CE, aimed not just to raid but to conquer and settle lands.

Led by legendary figures such as Ivar the Boneless, Halfdan Ragnarsson, and possibly Ubba (all believed to be sons of Ragnar Lodbrok), this army was far larger and better organized than previous Viking forces. It represented a coalition of Norse warriors from Denmark, Norway, and Sweden who sought permanent dominion over Anglo-Saxon England.

The Anglo-Saxon kingdoms at the time—Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia, and Wessex—were fragmented and often at odds with one another. This disunity made them vulnerable to the coordinated onslaught of the Viking invaders.

The Capture of York (866 CE)

York, known as Eoforwic by the Anglo-Saxons and originally founded as Eboracum during Roman times, was a thriving trading hub and one of England’s most significant cities. By 866 CE, it was the capital of Northumbria, although the kingdom itself was embroiled in a bitter civil war between rival claimants to the throne: King Ælla and Osberht.

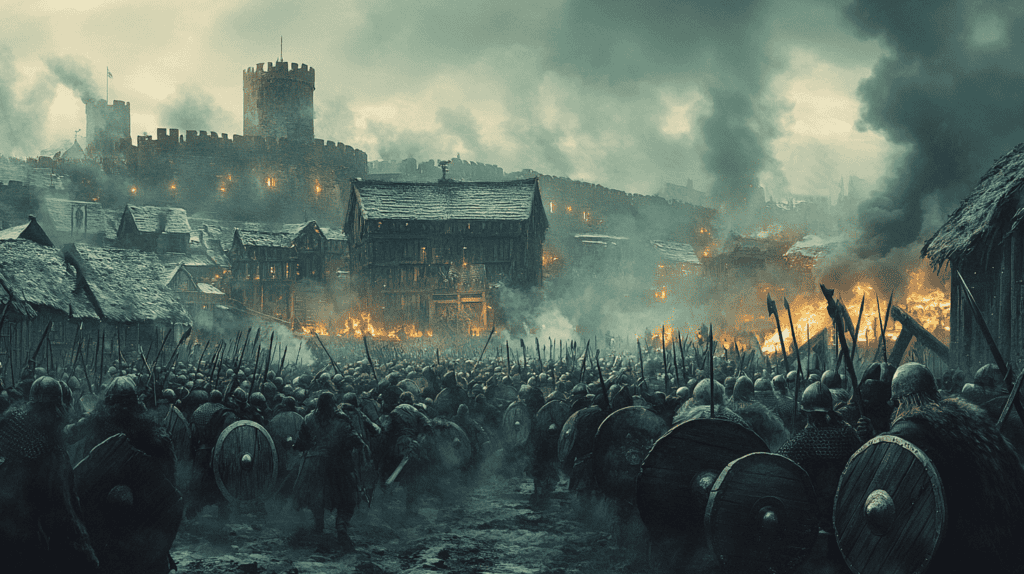

The Great Heathen Army seized this opportunity to strike. On November 1st, 866, under the leadership of Ivar the Boneless and Halfdan Ragnarsson, the Vikings launched a surprise attack on York. The timing was deliberate: All Saints’ Day meant many local leaders were likely attending religious observances, leaving the city vulnerable. The Vikings captured York with little resistance, establishing their foothold in Northumbria.

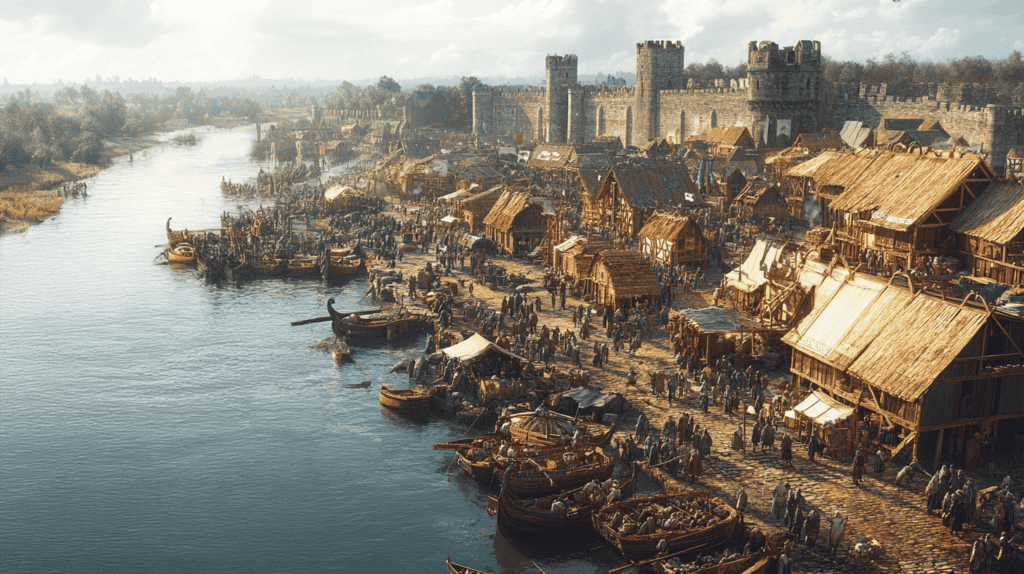

York’s capture was not just a military victory; it was also strategically significant. As a major urban center with access to trade routes along the River Ouse and Humber estuary, York provided an ideal base for further campaigns.

The Battle for Control: Ælla and Osberht’s Last Stand

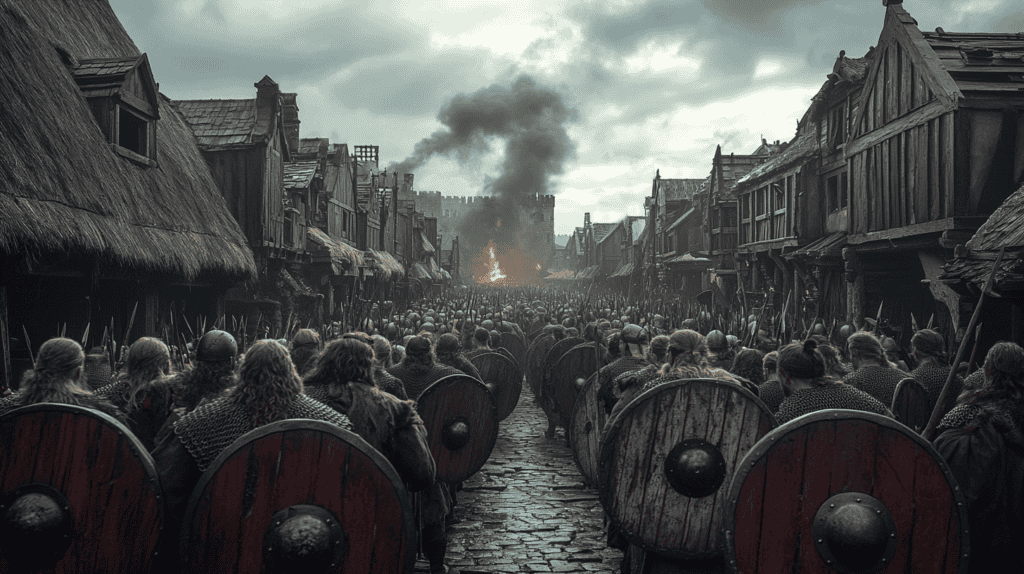

In early 867 CE, Ælla and Osberht set aside their rivalry to mount a united effort to reclaim York from Viking control. They gathered their forces and launched an assault on March 21st. Initially, they managed to breach York’s defenses and enter the city. However, this success was short-lived.

The Vikings regrouped within York’s narrow streets, where their superior tactics and experience in close-quarters combat turned the tide of battle. Both Ælla and Osberht were killed during this confrontation—a devastating blow to Northumbrian resistance.

According to some accounts, Ælla met a particularly gruesome fate at Ivar’s hands: he was subjected to the infamous “blood eagle” execution as revenge for Ragnar Lodbrok’s death.

With both rival kings dead, Northumbria fell under Viking control. The Great Heathen Army installed a puppet ruler named Ecgberht to govern on their behalf while they turned their attention to other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

York Becomes Jorvik

Following their conquest of Northumbria, the Vikings transformed York into Jorvik, making it the capital of their new kingdom. This marked a significant shift from raiding to settlement. Unlike earlier attacks that left destruction in their wake, Jorvik flourished under Norse rule.

The Vikings rebuilt much of York’s infrastructure, including its Roman walls and fortifications. Archaeological evidence suggests that they established a thriving commercial center between the fortress area and the River Ouse. Jorvik became an important hub for trade, connecting Scandinavia with Ireland, mainland Europe, and even distant regions like Byzantium.

Under Viking rule:

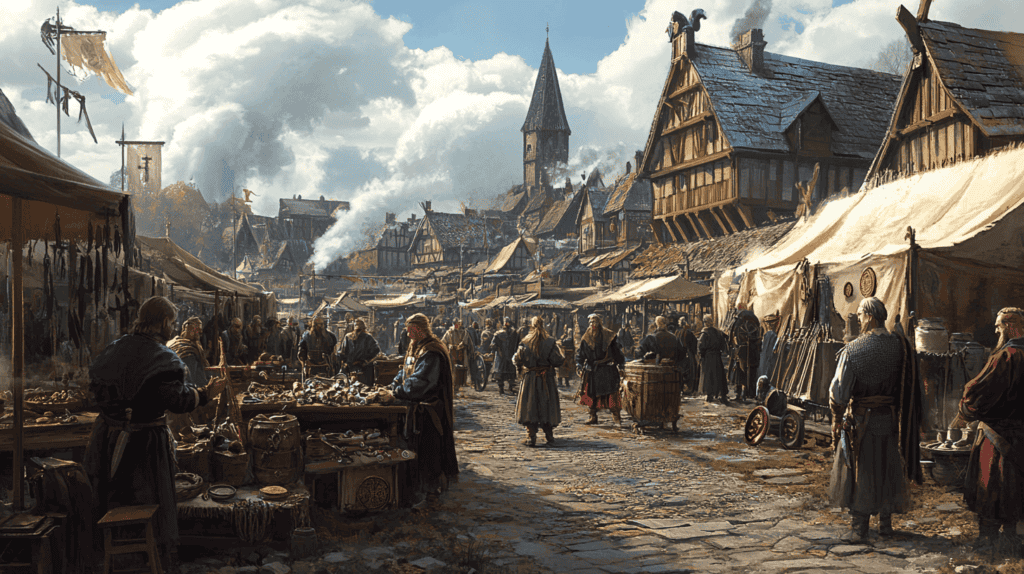

- Jorvik became known for its bustling markets where goods such as furs, amber, silver coins (dirhams), pottery, textiles, and slaves were traded.

- Scandinavian settlers introduced new agricultural practices and technologies.

- Norse culture blended with Anglo-Saxon traditions, influencing art, language (Old Norse words entered Old English), and governance.

The Danelaw: Dividing England

The establishment of Jorvik was part of a broader division of England into territories controlled by Vikings (the Danelaw) and those still under Anglo-Saxon rule. By 878 CE, following Alfred the Great’s victory over Guthrum at Edington and subsequent Treaty of Wedmore the Danelaw encompassed much of northern and eastern England and Jorvik served as its de facto capital.

This division created distinct cultural zones within England: in Viking-controlled areas like Jorvik, Norse customs dominated daily life, while in Anglo-Saxon territories such as Wessex (ruled by Alfred), efforts were made to consolidate power against future Viking incursions.

Jorvik’s Golden Age

During its peak under Viking rule (866–954 CE), Jorvik emerged as one of northern Europe’s most prosperous cities. Excavations at sites like Coppergate have revealed remarkable insights into life in Viking York. The city hosted people from diverse backgrounds—Scandinavians mingled with Anglo-Saxons, Irish traders, Picts from Scotland, and even merchants from Islamic lands.

Craftsmen produced high-quality goods such as jewelry (brooches), combs made from antlers, leather shoes, and textiles. Coins minted in Jorvik featured inscriptions in both Latin and Old Norse.

Religious life also adapted during this period. For while many Vikings initially adhered to pagan beliefs (worshipping gods like Odin), Christianity gradually gained influence as Alfred had expected. Churches were rebuilt or repurposed within Jorvik’s fortified core.

Decline of Viking Rule

By the mid-10th century, Viking dominance over northern England began to wane due to internal divisions among Scandinavian rulers and renewed pressure from Anglo-Saxon kings seeking to reclaim lost territories.

The last Norse king of York was Erik Bloodaxe. This son of Norwegian King Harald Fairhair, had carved a bloody path through 10th century Scandinavia and England. Beginning his Viking career at the tender age of 12, Erik quickly gained a reputation for ruthlessness that would follow him throughout his life.

After his father’s death, Erik’s bid for the Norwegian throne was marked by fratricide. He allegedly had four of his brothers killed to secure his position, earning him the chilling moniker “Bloodaxe”. However, his reign in Norway was short-lived. Ousted by his younger brother Haakon the Good, Erik set his sights on new conquests.

Fate led him to Northumbria, where he twice became King of York. His rule was tumultuous, marked by shifting alliances and constant threats. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recounts how Erik’s army dealt a devastating blow to King Eadred’s forces at Castleford, showcasing his military ability.

Yet, Erik’s fortunes were fleeting. In 954, he met his end on the bleak moors of Stainmore. Ambushed and outnumbered, Erik fell alongside five Hebridean kings and two earls of Orkney, a fittingly dramatic end for such a legendary figure. The skaldic poem Eiríksmál immortalizes his heroic entrance into Valhalla, ensuring that the name Bloodaxe will forever echo through the halls of Viking lore. However, with his death Norse Northumbria was absorbed into an increasingly unified English kingdom under King Eadred.