In the shadowy period following the collapse of Roman rule in Britain, a patchwork of small kingdoms emerged in what would become Wales. These realms, forged in the crucible of invasion and internal strife, played a crucial role in shaping Welsh identity and resisting external domination for centuries.

The Major Kingdoms Of Wales

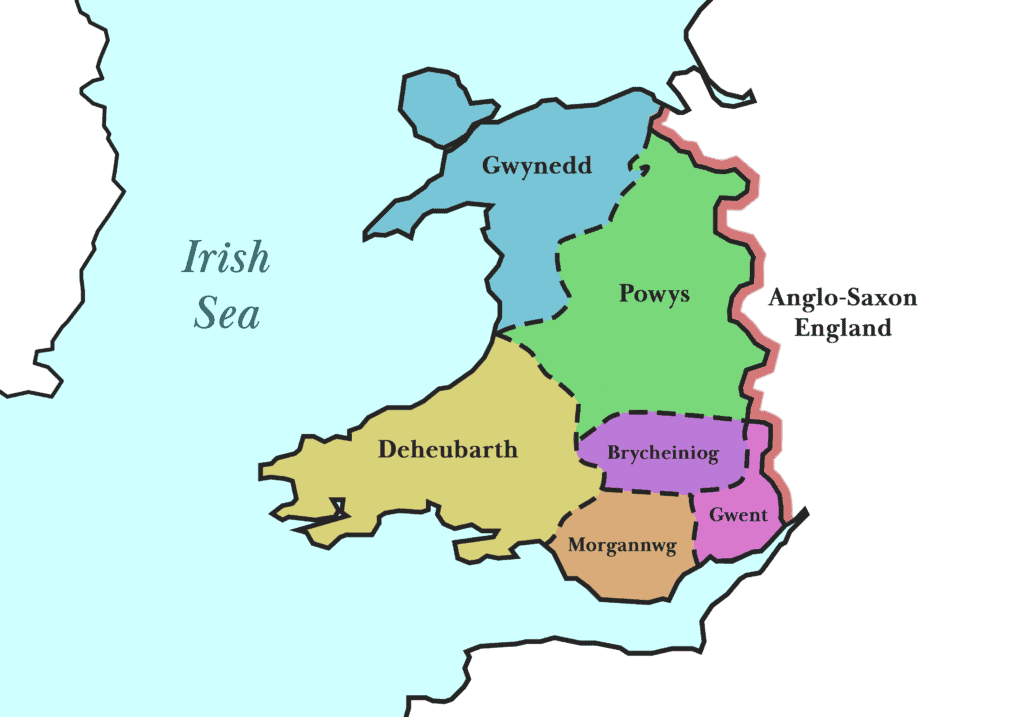

Three principal kingdoms dominated the Welsh political landscape:

- Gwynedd: Located in northwest Wales, Gwynedd emerged as the most powerful of the Welsh kingdoms in the 6th and 7th centuries.

- Powys: Situated in the east, Powys was a formidable realm that often found itself at the frontlines of conflicts with neighboring Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

- Deheubarth: Encompassing much of southwest Wales, Deheubarth would later play a significant role in Welsh resistance against Norman incursions.

These kingdoms, along with smaller realms like Gwent and Brycheiniog, formed the core of Welsh political power during the Dark Ages.

Rulers and Dynasties

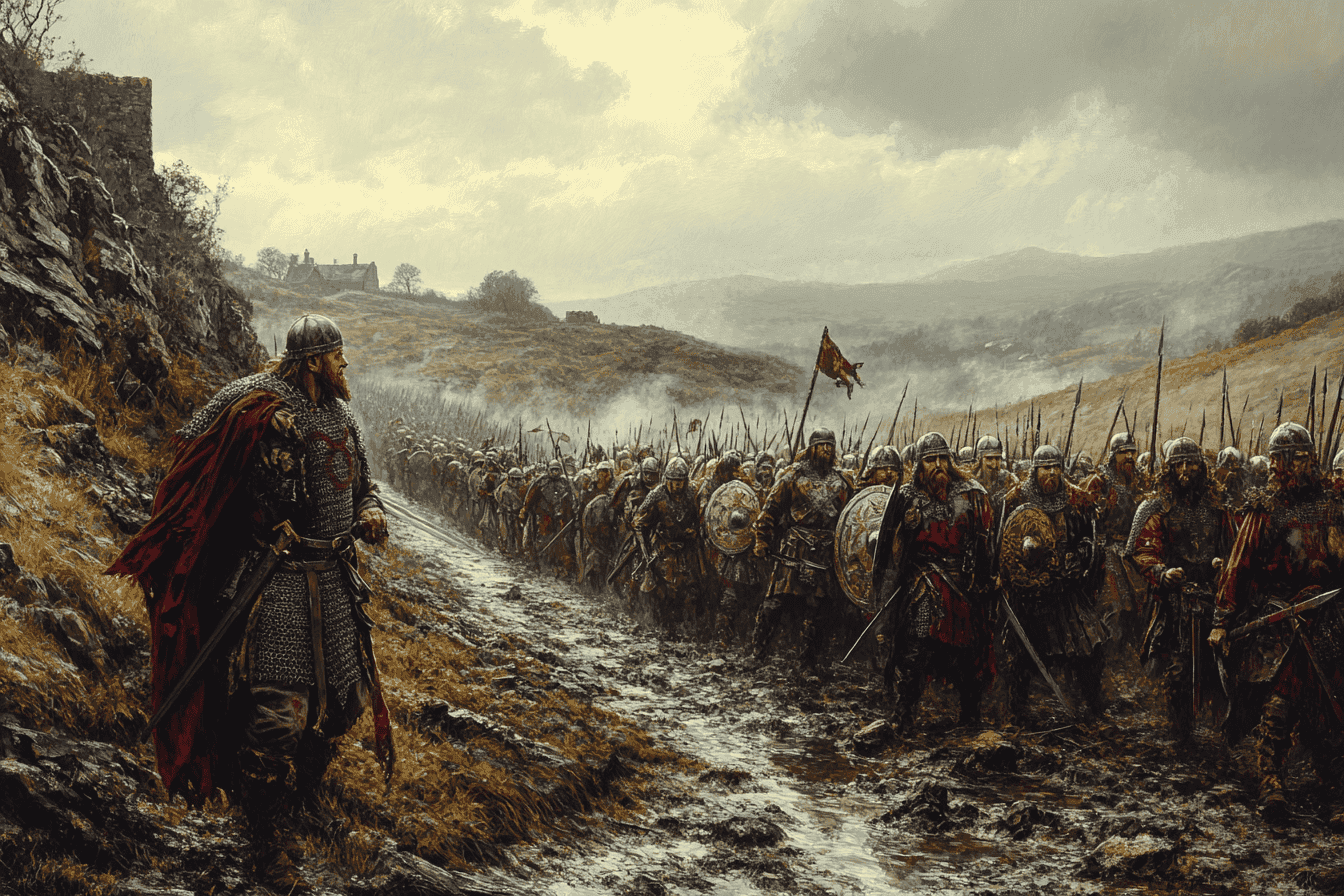

The history of Dark Age Wales is punctuated by the deeds of remarkable rulers who shaped the destiny of their kingdoms and, at times, the entire region.

Maelgwn Gwynedd

Maelgwn Gwynedd, a powerful 6th-century Welsh king, stands as a fascinating figure in British history, straddling the line between historical fact and Arthurian legend. Known as the “Dragon of the Isle,” Maelgwn ruled over the kingdom of Gwynedd in what is now northwestern Wales.

Maelgwn’s rise to power was marked by controversy. According to the 6th-century monk Gildas, Maelgwn murdered his uncle to claim the throne. Despite this ruthless beginning, he managed to gain the support of local lords and established himself as one of the pre-eminent rulers of Britain in his time. He expanded his influence beyond Gwynedd, with some sources suggesting he held sway in southwest Wales as well. His power was such that he was selected by the Picts to impregnate their queen, as both his grandmothers were Pictish.

Maelgwn’s life ended dramatically during a plague in 547 AD. Legend has it that he sought refuge in a monastery but couldn’t escape his fate.

Cadwallon ap Cadfan

Cadwallon ap Cadfan, King of Gwynedd from around 625 until his death in 634, stands as a pivotal figure in the tumultuous history of 7th-century Britain.

Cadwallon’s early years were fraught with challenges. The ambitious Edwin, King of Northumbria, had extended his rule to the “Mevanian Islands” – the Isle of Man and Anglesey – effectively besieging Cadwallon at Glannauc (now Puffin Island) in 629. Cadwallon escaped, spent time in Ireland before returning to Britain to confront Edwin.

The tide turned dramatically in Cadwallon’s favor three years later when he formed an alliance with Penda of Mercia. Together, they launched a devastating invasion of Northumbria, culminating in the Battle of Hatfield Chase on October 12, 633. This battle saw the defeat and death of Edwin and his son Osfrith, marking a significant victory for the Welsh.

Cadwallon’s subsequent rule over Northumbria was brief but impactful. Bede, an Anglo-Saxon chronicler, paints a scathing portrait of Cadwallon’s year-long reign, describing him as a “rapacious and bloody tyrant”. However, this characterization must be viewed critically, considering Bede’s bias and the complex political landscape of the time.

The Welsh king’s success was short-lived. A few months later, in late 633 or early 634, Cadwallon met his end at the Battle of Heavenfield, near Hexham. Oswald of Bernicia, leading a smaller force, surprised Cadwallon’s army in a night attack. The battle ended with Cadwallon’s death, halting the Welsh resurgence in its tracks.

Cadwallon ap Cadfan’s legacy is a complex one. To the Welsh, he was remembered as a national hero who nearly turned the tide against Anglo-Saxon expansion. To the Northumbrians, he was a fearsome conqueror who briefly subjugated their kingdom. His reign represents one of the last significant attempts by a Celtic British ruler to reclaim territories lost to the Anglo-Saxons.

Gruffudd ap Llywelyn

Gruffudd ap Llywelyn, born around 1010, stands as a pivotal figure in Welsh history, renowned as the first and only ruler to unite all of Wales under his command. His reign from 1055 to 1063 marked a unique period of Welsh unity and power that would not be seen again for centuries.

Gruffudd’s path to kingship began in 1039 when he became the ruler of Gwynedd and Powys. His early years were marked by conflict and expansion, and Gruffudd’s military acumen was evident from the start of his reign. In 1039, he achieved a significant victory against the forces of Anglo-Saxon Mercia at the Battle of Rhyd-y-groes, near present-day Montgomery and Welshpool. This triumph set the tone for his aggressive expansion policy, particularly along the eastern border with England.

By 1055, Gruffudd had achieved what no Welsh ruler before him had managed – the unification of Wales under a single crown. His domain stretched across the entirety of modern Wales, with only the sub-kingdom of Glamorgan remaining outside his direct control.

Tragically, Gruffudd’s rule came to an abrupt end on August 5, 1063, when he was killed in Snowdonia by his own men after defeat by the Anglo-Saxon Earl of Wessex and future Harold II. With his death, the brief period of Welsh unity collapsed, and the country once again fragmented into separate kingdoms.

Challenges and Conflicts

The Welsh kingdoms faced numerous challenges during this turbulent period, both from external threats and internal strife.

Viking Raids

Between 950 and 1000, Wales experienced increasing Viking attacks, particularly from Danish raiders. The worst raid for the Welsh was inflicted by the Norse-Gael sea lord Godfrey Haroldson (also known as Gofraid mac Arailt) in 987 CE. Haroldson, a formidable Viking raider, launched a devastating attack on the island of Anglesey in the Kingdom of Gwyndd, with a force that overwhelmed the local defenses. The assault was brutal and efficient, resulting in the capture of an astounding two thousand people.

The raid had significant repercussions for the Kingdom of Gwynedd, then ruled by Maredudd ab Owain. Faced with the loss of so many of his subjects, Maredudd was forced to take extraordinary measures. Reports suggest that he paid a ransom of one penny per captive in an attempt to secure the release of the Welsh prisoners.

Paying such a ransom to free his subjects from slavery demonstrated both the obligations on a king and the economic strain placed on the kingdom by the large-scale loss of an area’s farmers and crafts folk.

Inter-Kingdom Rivalries

The Welsh kingdoms were often embroiled in conflicts with each other. The law of succession, which divided land between sons or other male heirs, frequently led to bitter rivalries. In Powys, for example, 14 out of 24 men from the ruling dynasty were killed or maimed between 1075 and 1197!

Anglo-Saxon and Norman Threats

The kingdoms also faced constant pressure from Anglo-Saxon kingdoms to the east, particularly Mercia and Northumbria. This threat intensified with the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, which brought a new wave of aggressive expansion into Welsh territories.

The Most Castellated Country In Europe

The arrival of the Normans in 1066 marked a turning point in the history of the Welsh kingdoms. William the Conqueror established powerful Norman lords along the border with England, who soon made significant incursions into Wales. These lands along the English border, and incorporating the conquered Welsh territories, became known as the March. The Welsh still controlled the mountainous heartland of the country, but were always under threat from the Norman Marcher lords and their kings.

To help control the Welsh populace the Normans were forced to build impressive castles and established boroughs around them, creating a network of strongholds from which they could exert control over the surrounding areas. Incredibly, Wales has more castles per square mile than any other country in Europe: demonstrating the immense difficulty the Normans had in subduing the Welsh.

Certainly the geography of Wales lends itself to castle-building, with easily defendable mountains and valleys, which could be resupplied by river and sea. Often these Norman castles were built on the sites of former Welsh fortresses, which themselves were built over Roman or Iron Age forts, as they were situated at the naturally strategic points from which to control the surrounding land.

Political Identity

The memory of independent Welsh kingdoms fueled later resistance movements and helped maintain a distinct Welsh identity even under English rule. The title “Prince of Wales,” first claimed by native Welsh rulers, was later adopted by the English crown, a practice that continues to this day.

The story of these kingdoms is one of resilience in the face of overwhelming odds, of cultural flourishing amidst political turmoil, and of the enduring power of identity and tradition. As we look back on this tumultuous period, we see not just the struggles and defeats, but also the seeds of the vibrant Welsh culture that continues to thrive today.