The Rashidun Caliphate (632-661 CE) stands as one of the most transformative periods in world history. In less than three decades, four caliphs – Abu Bakr, Umar ibn al-Khattab, Uthman ibn Affan, and Ali ibn Abi Talib – led the nascent Muslim community from the Arabian Peninsula to the gates of Central Asia, North Africa, and the Mediterranean. Their conquests not only redrew the map of the ancient world but also laid the foundations for the Islamic civilization that would flourish for centuries.

The World Before the Rashidun

In the early 7th century, the Arabian Peninsula was a land of tribes, trade, and tradition, surrounded by two exhausted superpowers: the Byzantine Empire in the west and the Sasanian Empire in the east. Decades of war, plague, and internal strife had weakened both empires, leaving their borderlands vulnerable. Into this world, Islam emerged, uniting the fractious Arab tribes under a single religious and political banner.

Caliph 1. Abu Bakr (632–634 CE):

Uniting Arabia and the First Forays

The Ridda Wars: Securing the Heartland

After the death of the Prophet Muhammad in 632 CE, the young Muslim community faced an existential crisis. Tribes across Arabia rebelled, refusing to pay tribute or follow the new leadership. Abu Bakr, the first caliph, responded with determination, launching the Ridda Wars (“Wars of Apostasy”). In a series of fierce campaigns, he subdued the rebellious tribes, re-establishing unity and authority across the peninsula.

The First Conquests: Syria and Iraq

With Arabia united, Abu Bakr turned his gaze outward. He dispatched armies into Byzantine Syria and Sasanian Iraq, initiating the first phase of the Muslim conquests. These campaigns were not only military ventures but also missions imbued with religious zeal and the promise of booty and reward.

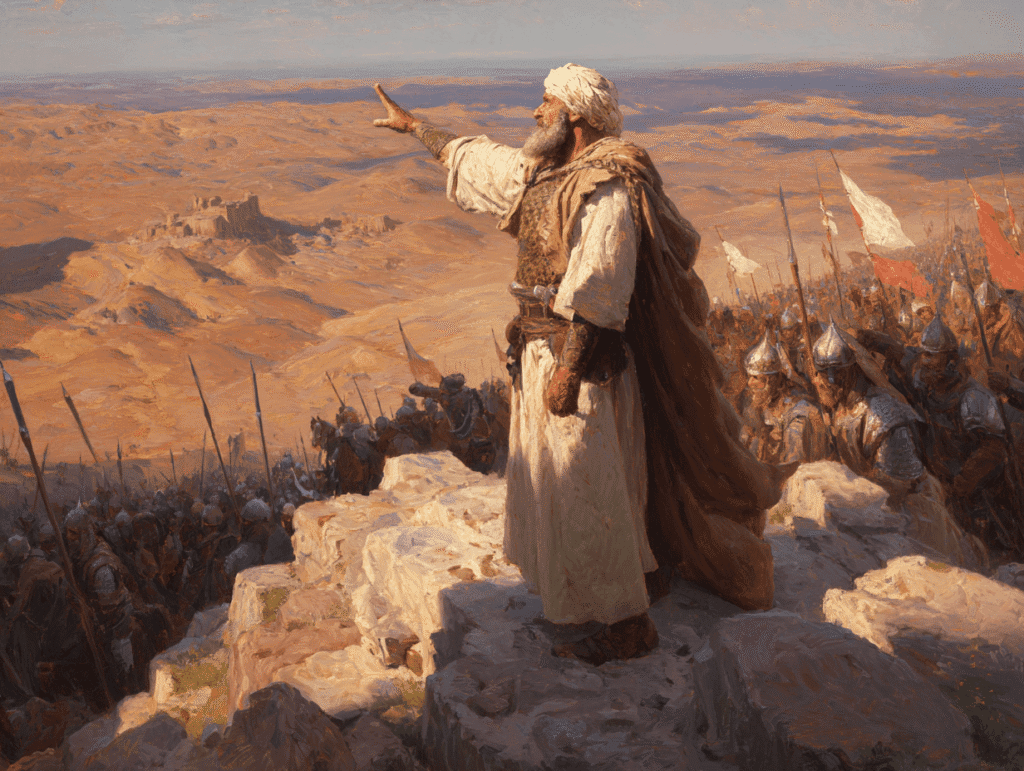

After successful campaigns in Iraq against the Sassanids, Abu Bakr turned his attention to Byzantine Syria, issuing a call to arms in early 634 CE. The Arab forces, led by the renowned general Khalid ibn al-Walid, moved swiftly into Syria. After capturing the city of Bosra, they learned of a large Byzantine force gathering at Ajnadayn. The Byzantines, underestimating the Arabs as mere local bandits, assembled local troops commanded by Theodore, brother of Emperor Heraclius, to confront the Muslim advance.

The Battle

The battle took place on an open plain near Ajnadayn in Palestine, a location traditionally identified between Ramla and Bayt Jibrin. Despite being outnumbered, the Muslim army displayed tactical superiority and fierce determination. Khalid ibn al-Walid’s cavalry played a decisive role, launching multiple charges that broke Byzantine formations. According to Muslim tradition, warriors like Dhiraar ibn al-Azwar distinguished themselves by slaying many Byzantine champions, including provincial governors.

The battle was intense and costly. Byzantine losses were heavy, with Arab casualties being relatively light in comparison, with estimates around 575 killed. The Byzantines eventually broke ranks and retreated in three directions: towards Gaza, Jaffa, and Jerusalem. Khalid pursued the fleeing troops relentlessly, inflicting further casualties.

The victory at Ajnadayn was a turning point in the Muslim conquest of Syria. It shattered Byzantine control over Palestine and opened the way for further Arab advances. The defeat forced Emperor Heraclius to withdraw from Emesa to Antioch, and Byzantine forces retreated to fortified towns, leaving the countryside vulnerable to Muslim raids. The psychological impact was profound, spreading panic among local populations and accelerating the collapse of Byzantine authority in the region.

Abu Bakr’s reign was brief, but his actions set the momentum for the explosive expansion that followed.

Caliph 2. Umar ibn al-Khattab (634–644 CE):

The Architect of Empire

The Siege of Damascus (634 CE)

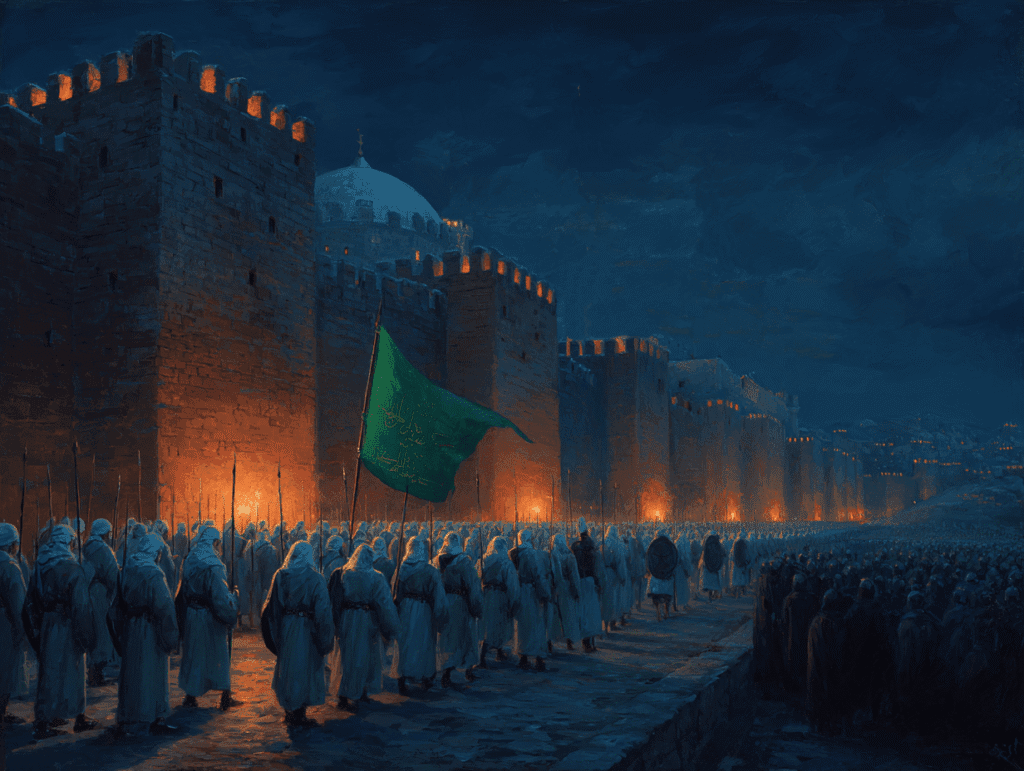

In the summer of 634, the Rashidun Caliphate, under the command of the legendary general Khalid ibn al-Walid, advanced into Byzantine Syria. Damascus, one of the region’s most fortified and prestigious cities, became their prime target. The city was defended by Thomas, the son-in-law of Emperor Heraclius, who prepared for a siege by sending out forces to delay the Muslim army’s advance. Despite these efforts, Khalid’s forces overcame Byzantine detachments in a series of bloody skirmishes, including the Battles of Yaqusa and Maraj as Saffer, before encircling Damascus on August 21.

The siege was a tense affair. The Byzantines, aware of the city’s strategic importance, launched desperate sorties to break the encirclement, while Heraclius dispatched a relief force of 12,000 men. Khalid, ever the tactician, sent a detachment north to intercept this force, resulting in the Battle of Uqab Pass, where the Byzantines were routed.

Inside Damascus, morale wavered. After nearly a month under siege, a monophysite bishop, perhaps motivated by religious or political grievances, revealed a lightly defended section of the city walls to Khalid. Under the cover of night, Khalid’s men stormed the eastern gate, while simultaneously, Thomas negotiated a peaceful surrender at the western Jabiyah gate with Khalid’s lieutenant, Abu Ubaidah. This led to confusion and dispute over the terms of surrender, but ultimately, the Muslim commanders honored Abu Ubaidah’s promise: the citizens would be spared, and the Byzantine garrison given three days to retreat unmolested.

Damascus fell on September 18, 634 – the first major Byzantine city to succumb to the Rashidun Caliphate. The city’s capture not only shattered Byzantine morale but also provided the Muslims with a vital base for further conquests. In time, Damascus would become the dazzling capital of the Umayyad Caliphate.

The Battle of Yarmouk (636 CE)

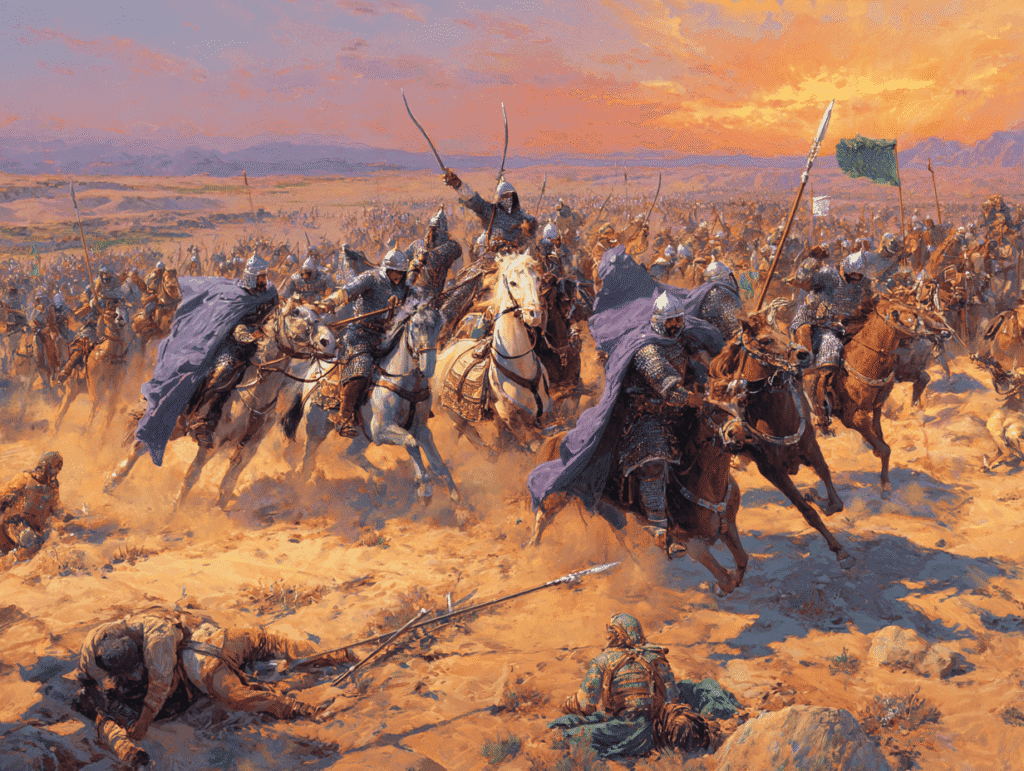

Two years later, the fate of the Levant would be decided on the windswept plains near the Yarmouk River. After the loss of Damascus, Emperor Heraclius marshaled a massive army, determined to reclaim Syria. The Rashidun forces, though outnumbered, were unified and inspired by their earlier victories.

The battle raged for six days in August 636, with both sides displaying extraordinary courage and tactical ingenuity. Khalid ibn al-Walid, once again leading the Muslim army, exploited the terrain and Byzantine overconfidence. He orchestrated feigned retreats, sudden cavalry charges, and relentless pressure on the Byzantine flanks. The Byzantines, hampered by internal divisions and the unwieldy size of their force, gradually lost cohesion.

On the final day, the Rashidun cavalry broke through, encircling and annihilating much of the Byzantine army. The defeat was catastrophic: tens of thousands of Byzantine soldiers perished, and the remnants fled north. The road to Syria and beyond now lay open to the Rashidun Caliphate.

The Fall of Persia

Umar’s armies then turned east, confronting the once-mighty Sasanian Empire – the second superpower of the region.

In November 636, near the banks of the Euphrates, the armies of the Rashidun Caliphate, led by Sa’d ibn Abi Waqqas, faced the formidable Sasanian forces commanded by the legendary general Rostam Farrokhzad. The Sasanian Empire, weakened by years of war with Byzantium and internal strife, was still a force to be reckoned with, fielding a massive army that dwarfed the Muslim ranks.

The battle raged for four days, with both sides displaying extraordinary valor and tactical ingenuity. The Persians relied on their famed heavy cavalry and war elephants, while the Muslims countered with agility, discipline, and a fervent belief in their cause. On the third day, a fateful sandstorm swept across the plain, blinding the Sasanian troops and sowing chaos in their ranks. In the confusion, Rostam was killed – some say by a falling tent pole, others by a Muslim warrior. With their general dead, the Persian lines collapsed. The Rashidun army surged forward, seizing a victory that would echo through history.

The consequences were monumental. The defeat at al-Qadisiyyah shattered Sasanian resistance in Mesopotamia. The Muslims pressed on to capture Ctesiphon, the Persian capital, and soon the heartland of Persia lay open before them.

Six years later, the battered remnants of the Sasanian Empire made a final stand at Nahavand, a strategic city nestled in the Zagros Mountains. Here, an army of up to 100,000 Persians, led by generals Piruz Khosrow and Mardanshah, confronted a smaller but determined Muslim force under Nu’man ibn Muqarrin. The Persians fortified themselves, hoping to stem the tide of conquest.

The Rashidun commander, feigned retreat, luring the Persians out of their stronghold into the open and treacherous terrain. Once the Sasanian cavalry was strung out and vulnerable, the Muslims rallied and counterattacked, encircling their foes. The ensuing melee was brutal—both Nu’man and Firuzan fell in the fighting, but the Persian army was annihilated.

Nahavand became known as the “Victory of Victories.” With their forces shattered, the Sasanians could never again muster a significant army. King Yazdegerd III fled east, and the empire crumbled, its provinces falling one by one to the Rashidun Caliphate. Persian nobles and officials, already disillusioned, abandoned the cause, and centuries of Zoroastrian imperial rule came to an end.

Egypt and Beyond

Not content with Syria and Persia, Umar’s forces pressed into Egypt.

After centuries as a cosmopolitan center of learning and commerce, Alexandria became the last bastion of Byzantine rule in Egypt, beset by the advancing armies of the Rashidun Caliphate under the command of Amr ibn al-As.

Alexandria’s defenses were formidable. Massive walls and towers protected the city on land, while the sea and the powerful Roman navy guarded its harbor. The city’s defenders, a mix of Byzantine soldiers and local militias, believed their position impregnable. The only viable approach for the besieging Arabs was a narrow front from the east, hemmed in by Lake Mareotis and a network of canals.

Amr ibn al-As, having already captured much of Egypt, knew Alexandria was the ultimate prize. His initial assault was met with a fierce and bloody repulse; the city’s ballistae and archers rained death upon the attackers, forcing the Arabs to withdraw and establish a camp out of range of the defenders’ missiles.

The siege did not unfold as a continuous battering of walls. Instead, it was characterized by tense negotiations and political maneuvering. The Greek Patriarch of Alexandria, Cyrus, saw the writing on the wall and brokered a treaty with Amr. The terms were harsh for the Byzantines: Egypt would pay a hefty tribute, the Roman garrison would evacuate Alexandria by sea, and the city’s Christians and Jews would be allowed to continue their worship without interference. An eleven-month armistice was agreed upon, during which the Arabs would not attack and the Romans would not attempt any hostile action.

When the people of Alexandria learned of the surrender, outrage swept the city. Furious mobs threatened Cyrus, blaming him for capitulation. Only his impassioned pleas that he had saved their lives calmed the unrest, at least temporarily.

Yet the story did not end with the treaty. News of the city’s fall reached Constantinople, and the Byzantine emperor dispatched a fleet of 300 ships under the command of Manuwil. In a dramatic reversal, the Byzantines retook Alexandria, slaughtering the Muslim garrison and briefly restoring imperial control.

But Amr ibn al-As was not to be denied. He returned at the head of 15,000 men, met the Byzantine force in open battle, and, after a fierce struggle, routed the defenders. The Byzantines retreated behind Alexandria’s walls, but this time, the Arabs brought up their own siege engines. The city, exhausted and isolated, finally capitulated for good in September 642 CE. The fall of Alexandria ended the seven-century-long Roman period in Egypt that had begun in 30 BC and, more broadly, the Greco-Roman period that had lasted about a millennium.

By the end of Umar’s reign, the Rashidun Caliphate stretched from Libya in the west to the borders of India in the east, encompassing vast and diverse peoples.

Caliph 3. Uthman ibn Affan (644–656 CE):

Expansion and Administration

Conquests In The North

Uthman inherited an empire in full expansion. He continued the campaigns of his predecessor, pushing the frontiers Northward.

The first Arab expeditions into Armenia began soon after the conquest of the Levant and Persia. In 639/640, Iyad ibn Ghanim led an initial foray as far as Bitlis, but these early raids met stiff resistance and limited success. A larger campaign in 642 faltered, with the Arabs pushed back by a coalition of Byzantine, Armenian, and allied Khazar and Alan forces.

However, the tide turned in 645/646, when Mu’awiya, the powerful governor of Syria, dispatched his general Habib ibn Maslama al-Fihri on a decisive campaign. Habib first targeted Theodosiopolis (modern Erzurum), capturing it after a siege and defeating a reinforced Byzantine army on the Euphrates. The campaign then moved towards Lake Van, where the local Armenian princes of Akhlat and Moks submitted, opening the way to Dvin, the capital of former Persian Armenia. Dvin surrendered after a brief siege, and soon Tiflis in Caucasian Iberia (modern Georgia) also capitulated.

The Arab strategy in Armenia was pragmatic. Rather than seeking wholesale destruction, they offered terms of surrender that allowed local rulers to retain a degree of autonomy in exchange for tribute, typically in the form of the jizya tax. This approach, combined with the exhaustion of local populations after decades of war between Byzantines and Persians, led many Armenian nobles to accept Muslim suzerainty with relatively little resistance. The conquest extended north to the Black Sea and into the Caucasus, where Muslim columns subdued districts such as Sharwan and Jabal.

In the Caucasus, the Muslim advance encountered the formidable Khazar Turks. While initial clashes, such as the siege of Belencer, were fierce, the Muslims ultimately secured control of the southern Caucasus, though the north remained outside their grasp. The Georgians and other local peoples were brought under Muslim authority, further expanding the frontiers of the Caliphate.

The Conquest of North Africa

After the fall of Egypt to Arab forces in 642, Uthman turned his attention to the lands further west, known as the Maghreb – modern Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco. The region was then a patchwork of Byzantine strongholds and fiercely independent Berber (Amazigh) tribes. The initial Arab raids into Berber territories began soon after Egypt’s conquest, but it was under the Umayyad Caliphate, with its capital in Damascus, that the campaign gained momentum.

The March West and the Founding of Kairouan

The first major push came in the late 7th century. In 670, the Arab general Uqba ibn Nafi led a force from Damascus deep into North Africa, founding the city of Kairouan (south of modern Tunis) as a military base and refuge. This city would become the capital of the province of Ifriqiya, covering much of present-day Tunisia, western Libya, and eastern Algeria. Uqba’s legendary march took him as far as the Atlantic coast, symbolizing the vast reach of the early Islamic conquests.

The Fall of Carthage and the End of Byzantine Rule

The conquest was not without setbacks. Berber resistance was fierce, and the Byzantines, though weakened, still held key coastal cities. In 698, after a series of hard-fought battles, Arab forces under Hassan ibn al-Nu’man captured Carthage, the ancient city that had long been a bastion of Greco-Roman and Christian influence. Anticipating Byzantine attempts at reconquest, the Arabs destroyed Carthage’s fortifications and infrastructure, shifting their base to Tunis while Kairouan remained the administrative capital.

Berber Resistance

The conquest did not immediately bring peace. The Berbers, led by their legendary queen Kahina, mounted a formidable rebellion that temporarily drove the Arabs back to the borders of Egypt. However, after several years and the arrival of reinforcements, the Arabs returned, defeated Kahina, and reasserted control. The subsequent governor, Musa bin Nusair, brutally suppressed further resistance, enslaving and deporting large numbers of Christian Berbers. Despite this violence, the spread of Islam among the Berber population was not simply the result of force; the new faith resonated with many, and by the 11th century, the Berbers were largely Islamized and, to a significant extent, Arabized.

The Arab Conquest of Cyprus

While the conquest of North Africa was a protracted land campaign, the Arab incursion into Cyprus unfolded primarily by sea, reflecting the growing naval ambitions of the early Caliphate.

In 649 AD, under the leadership of Muawiyah I, then governor of Syria, a Muslim fleet set sail from Alexandria and attacked Cyprus. The capital, Salamis-Constantia, fell after a brief siege. According to tradition, a relative of the Prophet Muhammad, Umm Haram, accompanied the expedition and died in an accident near Larnaca; her tomb, the Hala Sultan Tekke, remains a revered site to this day.

The initial conquest was followed by a treaty with the local rulers: Cyprus would pay an annual tribute, refrain from hostility, and alert the Caliphate to any Byzantine military movements. A garrison of 12,000 Arabs was stationed on the island, solidifying Muslim control. However, the island’s fate remained contested. In 688, a unique arrangement was reached: the Byzantine emperor Justinian II and the Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik agreed to govern Cyprus jointly, dividing its tax revenues and maintaining a delicate balance of power. This condominium lasted, with interruptions, for nearly three centuries.

Internal Strife

Uthman is perhaps best remembered for his administrative and religious reforms. Above all, to preserve the unity of the Muslim community, Uthman ordered the compilation and standardization of the Qur’an, sending copies to all corners of the empire.

However, Uthman’s reliance on his Umayyad relatives for key positions bred resentment and unrest, sowing the seeds of internal conflict. Discontent simmered across various provinces, culminating in a rebellion in 656 CE. A group of disgruntled soldiers and citizens from Egypt and Iraq eventually laid siege to his house in Medina. Despite efforts by prominent companions of the Prophet Muhammad to mediate the crisis, the siege ended with Uthman’s brutal murder. His death not only shocked the Muslim community but also triggered the first major civil war (fitna) within Islam, fracturing the ummah and leading to enduring sectarian divisions.

Caliph 4. Ali ibn Abi Talib (656–661 CE):

Civil War and the End of Expansion

The First Fitna

Ali’s accession to the caliphate came in the shadow of Uthman’s assassination. His reign was marked by the First Fitna, the first major civil war in Islam’s short history.

The Battle of the Camel (656 CE): A Fractured Brotherhood

The Battle of the Camel, fought outside Basra in December 656 CE, was the first major clash of the First Fitna. On one side stood Ali ibn Abi Talib, cousin and son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad, now the fourth caliph. On the other, a coalition led by Aisha (widow of Muhammad), and the prominent companions Talha and Zubayr. Their rallying cry was vengeance for Uthman’s murder and a demand for a new caliph chosen by a Qurayshite council, with Talha and Zubayr as possible candidates.

The rebels seized Basra, defeating Ali’s governor and killing many of his supporters. Ali, after gathering reinforcements in Kufa, marched on Basra. For three days, negotiations failed. On the afternoon of December 8, battle erupted. Zubayr, troubled by doubts, left the field but was pursued and killed. Talha fell to a supporter of the Umayyads. The fighting raged until Ali’s troops killed the camel upon which Aisha sat, around which her supporters had rallied. With the deaths of Talha and Zubayr, and Aisha’s capture, the battle ended in Ali’s favor.

Ali treated Aisha with dignity, sending her back to Medina under escort. He issued a general pardon, even to high-profile rebels like Marwan ibn al-Hakam, who would soon join forces with Muawiyah, governor of Syria. The battle left deep scars: revered companions had fought – and died – against each other, and the unity of the early Muslim community was irreparably fractured.

The Battle of Siffin (657 CE): The Stalemate of Titans

The next year, the struggle for legitimacy moved north to the plain of Siffin, near the Euphrates. Here, Ali faced Muawiyah ibn Abi Sufyan, the powerful governor of Syria and kinsman of Uthman, who refused to recognize Ali’s caliphate and demanded vengeance for Uthman’s death.

The armies were vast: Muawiyah reportedly commanded 120,000 men, Ali 80-90,000. After months of skirmishes and failed negotiations, the main battle erupted in July 657 CE. The fighting was brutal and costly – tens of thousands perished, including many veteran companions of the Prophet.

As Muawiyah’s forces neared defeat, they resorted to a dramatic ruse: hoisting copies of the Qur’an on their lances, they called for arbitration by God’s word. This act sowed confusion in Ali’s ranks, many of whom refused to continue fighting against fellow Muslims who invoked the Qur’an. Reluctantly, Ali agreed to arbitration, a decision that would haunt him. The battle ended inconclusively, with no clear victor. The subsequent arbitration failed to resolve the dispute, and the caliphate remained contested.

The Battle of Nahrawan (658 CE): The Tragedy of the Kharijites

The aftermath of Siffin saw the emergence of a radical faction: the Kharijites. Disillusioned by Ali’s acceptance of arbitration, which they saw as a betrayal of God’s sovereignty, they broke away and began attacking civilians. Ali attempted reconciliation, but when negotiations failed, he marched against them.

The confrontation took place at Nahrawan in 658 CE. Ali’s forces, vastly outnumbering the Kharijites, offered them a chance to surrender. Most refused. The ensuing battle was a massacre: almost all the Kharijites were killed, with only a handful surviving. Though victorious, Ali’s heart was heavy; the Kharijites had once been his most zealous supporters, and their destruction marked another tragic chapter in the civil strife.

The Limits of Conquest

These three battles – Camel, Siffin, and Nahrawan – were not just military encounters but seismic events that shaped the trajectory of Islamic history. They marked the end of the era of consensus and the beginning of enduring sectarian divisions. The deaths of so many companions and the spectacle of Muslims fighting Muslims left wounds that would never fully heal. The First Fitna, culminating in Ali’s assassination in 661, set the stage for the Umayyad dynasty and the eventual crystallization of Sunni and Shia identities.

During Ali’s caliphate, the focus shifted from external conquest to internal consolidation. The empire’s borders remained largely unchanged, and the energies of the state were consumed by civil war. Ali’s assassination in 661 CE marked the end of the Rashidun era and the rise of the Umayyad dynasty.

The Legacy of the Rashidun Conquests

The Rashidun caliphs generally governed their vast empire with a light touch, generally allowing local populations to retain their religions and customs in exchange for tribute. This pragmatic approach facilitated the relatively smooth integration of diverse peoples into the Islamic world.

The Rashidun conquests were driven by a combination of religious fervor, strategic brilliance, and the unique circumstances of the time, specifically the weakness of the Byzantine and Sassanid empires. Their conquests reshaped the political, religious, and cultural landscape of the Middle East and beyond – a legacy that endures to this day.