The Peace and Truce of God movements were two closely related initiatives launched by the early medieval Catholic Church to promote peace and curb the endemic violence of feudal society in Western Europe after the collapse of the Carolingian Empire in the 9th century. They stand as some of the earliest and most influential popular peace movements in history, marking a significant attempt to restrain private warfare by using the moral and spiritual authority of the Church.

Origins and Context

Following the 9th-century disintegration of central imperial power in what is now France and surrounding regions, local lords and knights frequently engaged in private feuds and small-scale wars that devastated communities, ecclesiastical properties, and peasants. The political landscape fragmented into numerous small lordships, where violence was an important means of asserting power. Central authorities were too weak to enforce law and order effectively, creating an environment where violence could spiral unchecked. This social chaos sparked deep anxieties and demands for peace from the clergy and common people alike.

The Peace of God (Pax Dei)

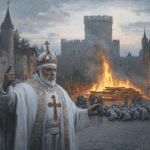

The Peace of God movement began around 989 at the Council of Charroux in southern France, led by bishops aiming to protect vulnerable segments of society and church property from violence. It prohibited attacks on noncombatants such as peasants, clergy, women, pilgrims, and merchants, as well as the destruction of church lands and goods. The Peace of God sought to sacralize certain spaces and peoples, forbidding their violation under the threat of ecclesiastical sanctions like excommunication.

Its enforcement was supported by popular participation – village leaders and nobles swore oaths to uphold the peace, reflecting broad support beyond the clergy. The movement spread across France during the early 11th century, aided by influential institutions like the Cluny Abbey, which extended church protection over large areas. Cluny’s independence from secular rulers and its moral prestige helped push the Peace of God across many regions. The movement also gained royal backing, notably from King Robert II of France, who saw its value in maintaining tranquility where his direct power was limited.

The Peace of God was somewhat revolutionary in binding even nobles and knights to restraints, promoting a societal ethic that went beyond secular law – an early form of what would later become the chivalric code emphasizing protection of the weak and orderly conduct in warfare.

The Truce of God (Treuga Dei)

Starting in the 11th century, particularly marked by a 1027 council in Toulouges, the Truce of God extended the Peace movement’s aims by seeking to regulate the timing of violence, not just its targets. The Truce prohibited warfare on specific days of the week (such as Sundays and certain feast days) and during certain liturgical seasons like Lent and Advent – times traditionally considered sacred and thus inappropriate for bloodshed.

This truce on violence sought to create interruptions in the cycle of warfare, offering periods of enforced peace for Christian communities to worship, work, and live without fear of attack. Over time, the truce came to encompass about 80 days annually, severely restricting when nobles and knights could legitimately wage war. The initiative gained wide acceptance across France and spread to Italy and Germany, eventually becoming church law through decrees in major church councils, including the Lateran Councils and the Council of Clermont.

The Truce of God was more temporal and ritualistic compared to the Peace of God; it did not specifically protect certain classes of people but rather imposed a rhythm of peace by banning fighting on defined days and seasons, reinforcing the sacredness of time in Christian life.

Impact on Medieval Society and Knightly Warfare

Together, the Peace and Truce of God movements gradually instilled moral and social restraints on the warrior class. They forced knights and lords to reconsider their conduct, with the threat of severe spiritual penalties (like excommunication) acting as a deterrent against reckless violence. These movements helped articulate emerging ideals of chivalry, where knights bore responsibilities beyond battlefield prowess, including protecting the vulnerable and upholding peace.

The Church’s role as a peacekeeper enhanced its moral authority and influence over secular matters, positioning it as a guardian of social order amid political fragmentation. While enforcement was often inconsistent – especially given resistance from powerful lords who saw their feuding rights restricted – the popular enthusiasm for peace and the Church’s backing meant the movements had lasting cultural resonance.

Limitations and Legacy

The Peace and Truce faced challenges due to the fragmented nature of medieval political power. Many local lords ignored or resisted the decrees, and enforcement mechanisms remained weak. The movements’ effectiveness varied widely by region and over time. Still, by the 12th century, the combined efforts of kings, nobles, clergy, and populations had embedded the ideas of limited violence and protection of the noncombatant into European medieval political culture.

By the 13th century, as centralized monarchies strengthened and state power increased, the Church’s direct role in enforcing peace waned, transitioning towards “the king’s peace” as the secular authority grew stronger, yet the ideals promoted by the Peace and Truce persisted in the codes of conduct for knights and in European legal frameworks going forward.