Early Contacts and Influences

The relationship between the Byzantine Empire and the Slavic peoples of Eastern Europe began long before the official conversion of Kievan Rus’. Byzantine traders and missionaries had been active in the region for generations, introducing elements of their culture and religion to the Slavic tribes. These early contacts laid the groundwork for future religious and cultural exchanges.

In 867, Patriarch Photius of Constantinople reported enthusiastic conversions among the Rus’ people. However, these early efforts did not lead to lasting changes, as Slavic paganism remained firmly entrenched in the region for over a century afterward.

Vladimir the Great makes the decision

The central figure in the Christianization of Kievan Rus’ was Prince Vladimir the Great, who ruled from 980 to 1015. Vladimir’s conversion and subsequent efforts to Christianize his realm are the subject of numerous historical accounts and legends.

According to traditional narratives, Vladimir’s decision to adopt Christianity was preceded by a period of religious exploration. He reportedly sent envoys to study various religions, including Islam, Judaism, and both Western and Eastern Christianity. The envoys were most impressed by the beauty and grandeur of Orthodox Christian worship in Constantinople, which played a significant role in Vladimir’s ultimate choice.

However, political considerations were also crucial in Vladimir’s decision. The Byzantine Empire was the most powerful and culturally advanced neighbor of Kievan Rus’, and aligning with it through religious conversion offered significant advantages.

The Conversion Process

The exact details of Vladimir’s conversion are subject to debate among historians, with different sources providing varying accounts. However, most agree on several key events:

Vladimir formed an alliance with Byzantine Emperor Basil II, who was facing a rebellion near Constantinople. In exchange for military assistance, Vladimir sought a royal marriage alliance. In 988, Vladimir was baptized into the Orthodox faith, taking the Christian name Basil. He then married Anna Porphyrogenita, sister of Emperor Basil II.

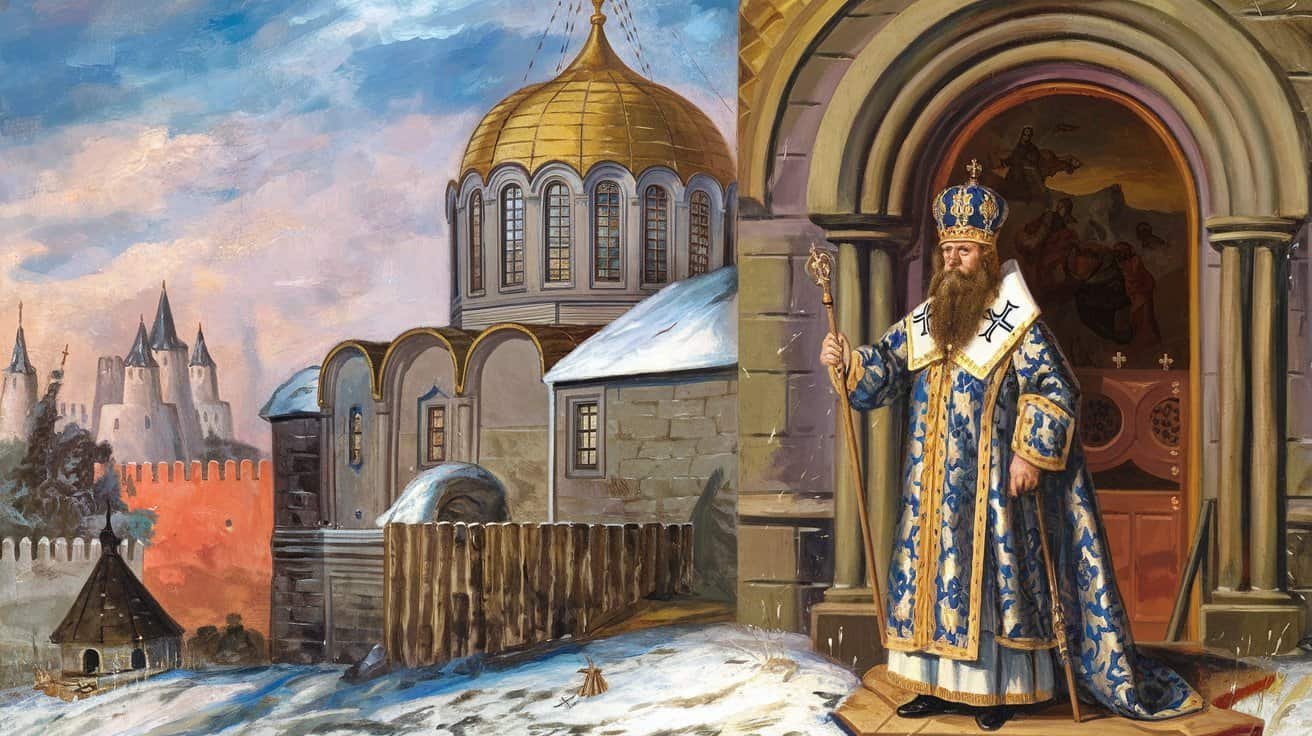

Upon returning to Kiev with his new bride in 988, Vladimir ordered the destruction of pagan temples and idols, marking the official beginning of Christianization in Kievan Rus’. Vladimir organized a mass baptism of the people of Kiev in the Dnieper River, an event that has become iconic in the history of Eastern Slavic Christianity. In 989, Vladimir began construction on the Church of the Tithes in Kiev, the first stone church in the city, symbolizing the new Christian era.

Impact and Legacy

The adoption of Orthodox Christianity from Byzantium had profound and far-reaching consequences for Kievan Rus’ and its successors.

Cultural and Intellectual Transformation

The conversion opened Rus’ to Byzantine culture, literature, and learning. Greek works were translated into Slavic languages, and Byzantine art forms, particularly the painting of icons, became integral to Russian culture. This influx of Byzantine influence contributed to the development of a distinct Slavic-Orthodox cultural identity.

The Orthodox Church played a crucial role in spreading literacy throughout Rus’. Priests and monks, many of whom came from Byzantium, taught reading and writing, establishing the foundations for a literate society.

Political Implications

By adopting Orthodox Christianity, Vladimir aligned Kievan Rus’ with the Byzantine Empire, the most powerful and sophisticated state in the region. This alliance brought prestige and legitimacy to the Rus’ rulers. However, unlike in Western Europe, where the Catholic Church often exerted significant influence over secular rulers, the Orthodox model allowed for greater independence of the Rus’ state from ecclesiastical authority.

The Third Rome

The Russian Orthodox Church was established as an autonomous entity within the broader Orthodox world. While initially under the jurisdiction of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, it gradually developed its own hierarchy and traditions. This structure allowed for the development of a distinctly Russian form of Orthodoxy over time.

The adoption of Orthodox Christianity became a cornerstone of Russian national identity. Even during periods of political fragmentation or foreign domination, the shared Orthodox faith served as a unifying factor for Eastern Slavic peoples.

After the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, Russian rulers began to see themselves as the heirs to the Byzantine legacy. Moscow was proclaimed the “Third Rome,” positioning Russia as the defender and continuator of Orthodox Christian civilization.

The Byzantine model of close cooperation between church and state, known as symphonia, became deeply ingrained in Russian political culture. This relationship persisted, in various forms, through the tsarist period and even influenced church-state dynamics in the Soviet and post-Soviet eras.

Challenges and Continuities

The Christianization of Rus’ was not a smooth or immediate process. Pagan beliefs and practices persisted for generations, especially in rural areas, leading to a form of “double faith” (dvoeverie) where Christian and pagan elements coexisted.

Moreover, the conversion was not always peaceful. Vladimir’s destruction of pagan shrines and forced baptisms met with resistance in some areas. The process of fully integrating Orthodox Christianity into all levels of society took centuries.