The First Iconoclasm (726-787 CE)

The seeds of the controversy were sown in the early 8th century, as the Byzantine Empire faced mounting pressures from external threats, particularly the expanding Islamic caliphate. In 726 CE, Emperor Leo III the Isaurian took a bold and controversial step that would ignite a century-long conflict.

According to traditional accounts, Leo III ordered the removal of an icon of Christ from the Chalke Gate, the main ceremonial entrance to the Great Palace of Constantinople. This act, whether historically accurate or embellished by later iconophile writers, marked the beginning of the imperial policy of Iconoclasm – the rejection and destruction of religious images.

Leo III’s motivations for this drastic action were multifaceted. Some scholars suggest that he was influenced by the Islamic prohibition of figurative art, seeking to emulate the military successes of the Muslim armies. Others point to theological concerns about idolatry and the proper veneration of the divine. Whatever the reasons, the emperor’s decision sent shockwaves through Byzantine society.

The implementation of Iconoclasm was met with fierce resistance from various quarters. Monks, who were often skilled icon painters and guardians of religious traditions, became the most vocal opponents of the new policy. The Papacy in Rome, already growing distant from Constantinople, firmly supported the use of religious images, further widening the rift between East and West.

As the controversy intensified, Leo III’s son and successor, Constantine V (741-775 CE), took an even harder stance against icons. Under his reign, the persecution of iconophiles (supporters of icons) reached new heights. In 754 CE, Constantine V convened the Council of Hieria, which formally condemned the veneration of icons and anathematized key defenders of images, including John of Damascus.

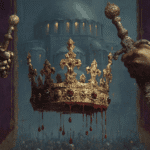

The iconoclasts argued that the use of religious images bordered on idolatry, violating the Second Commandment’s prohibition against graven images. They promoted the cross as the only acceptable symbol for Christian worship. Iconophiles, on the other hand, insisted on the symbolic nature of icons and their importance in facilitating devotion and understanding of divine mysteries.

The destruction of icons during this period was widespread and devastating. Countless works of religious art were defaced, plastered over, or completely destroyed. The loss to Byzantine cultural heritage was immense, with many irreplaceable masterpieces lost forever.

However, the tide began to turn in the latter half of the 8th century. Empress Irene, who ruled as regent for her young son Constantine VI, was sympathetic to the iconophile cause. In 787 CE, she convened the Second Council of Nicaea, which reversed the decisions of Hieria and restored the veneration of icons. This marked the end of the First Iconoclasm, but the controversy was far from over.

The Interlude and Second Iconoclasm (815-843 CE)

The period between 787 and 815 CE saw a temporary restoration of icon veneration. However, the underlying tensions remained unresolved. In 815 CE, Emperor Leo V the Armenian revived the iconoclastic policy, ushering in the Second Iconoclasm.

This renewed phase of the controversy was triggered by a series of military defeats, particularly against the Bulgars in Macedonia and Thrace. Leo V, like his predecessors, interpreted these setbacks as divine punishment for the empire’s perceived idolatry. The ban on images was reinstated, although historical evidence suggests that this second phase was less severe than the first.

Despite the imperial policy, resistance to Iconoclasm persisted. Theodore, the abbot of the Stoudios Monastery in Constantinople, emerged as a prominent defender of icons during this period. His writings and leadership provided crucial support for the iconophile cause.

The Second Iconoclasm continued under subsequent emperors, including Michael II and Theophilus. However, the tide of popular opinion was increasingly turning against the iconoclasts. The long years of conflict had taken their toll on Byzantine society, and many yearned for a resolution to the divisive issue.

The Triumph of Orthodoxy

The final chapter of the Iconoclastic Controversy unfolded in 843 CE, during the regency of Empress Theodora for her young son Michael III. In a decisive move, Theodora convened a council that officially restored the veneration of icons. This event, known as the Triumph of Orthodoxy, is still celebrated in the Eastern Orthodox Church on the first Sunday of Lent.

The restoration of icons was not merely a religious decision; it had profound implications for Byzantine art, culture, and politics. The post-Iconoclasm period saw a flourishing of religious art, with new styles and subjects emerging. The development of standardized programs for church decoration and the evolution of distinct portrait types for individual saints were direct consequences of the controversy.

Legacy and Impact

The Iconoclastic Controversy left an indelible mark on Byzantine history and the broader Christian world. It contributed to the growing schism between the Eastern and Western churches, as Rome’s support for icons further distanced it from Constantinople.

The controversy had significant political ramifications as well. It highlighted the complex relationship between church and state in Byzantium, with emperors actively shaping religious policy. The struggle also affected the empire’s social fabric, creating divisions between different segments of society and challenging established hierarchies.

In the realm of art and culture, the Iconoclastic Controversy paradoxically led to a renewed appreciation for religious imagery. The post-Iconoclasm period saw a revival of icon production, with artists developing new techniques and styles to convey spiritual truths. The experience of loss during the iconoclastic years instilled a deeper reverence for religious art among the Byzantine populace.

The effects of the controversy extended far beyond the borders of the Byzantine Empire. The debate over religious images would resurface centuries later during the Protestant Reformation, with reformers echoing many of the arguments put forth by the Byzantine iconoclasts.