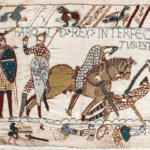

The Danish invasion of England in 1069, and William the Conqueror’s brutal response was a significant moment in the tumultuous period following the Norman Conquest. This event, overshadowed by the more famous Battle of Hastings in 1066, played a crucial role in shaping the early years of Norman rule in England and highlighted the fragility of William’s hold on his newly acquired kingdom.

Background: The Aftermath of Hastings

The Norman Conquest of England, initiated by William the Conqueror‘s victory at the Battle of Hastings in 1066, did not immediately secure Norman control over the entire country. In the months following William’s coronation, pockets of resistance emerged across England, particularly in the north. The Anglo-Saxon nobility, many of whom had survived the battle, were not content to simply accept Norman rule and began organizing rebellions against the new regime.

William’s initial strategy to consolidate his power involved a combination of military force and political maneuvering. He began constructing castles in key locations, a novel defensive strategy in England at the time, which allowed him to establish strongholds of Norman authority. However, these efforts were primarily focused on the south and central regions of England, leaving the north relatively untouched by direct Norman control.

The Danish Connection

Denmark, under the rule of King Sweyn II Estridsson, had long-standing ties to England. The Danish royal family claimed a right to the English throne, a claim that dated back to the reign of Cnut the Great in the early 11th century. This historical connection, combined with the cultural and commercial links between northern England and Scandinavia, made Danish intervention in English affairs a constant possibility.

The opportunity for Danish involvement arose in the wake of the Norman Conquest. Many English nobles who opposed William’s rule saw the Danes as potential allies in their struggle against Norman domination. The prospect of Danish support gave hope to those who wished to reverse the outcome of Hastings and restore Anglo-Saxon rule.

The Invasion Begins

In August 1069, King Sweyn II launched a massive invasion fleet towards England. Contemporary sources estimate the size of this fleet at between 240 and 300 ships, carrying a formidable army recruited not only from Denmark but also from Norway, Frisia, Saxony, Poland, and even Lithuania. This multinational force was led by Sweyn’s sons Harald and Cnut, along with his brother Asbjørn, rather than by the king himself.

The Danish fleet’s initial attempts to land in southern England were thwarted. They were repulsed at both Dover and Sandwich in Kent, forcing them to sail northward in search of a more favorable landing site. After unsuccessful attempts at Ipswich and Norwich, the Danes finally made a successful landing in the Humber estuary, a strategic entry point to northern England.

Alliance with English Rebels

The arrival of the Danish force in the north galvanized local resistance against Norman rule. Various English leaders, including Waltheof, Gospatric, and Edgar Ætheling (a claimant to the English throne), joined forces with the Danes. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reports that “all the people of the country” rallied to their cause, suggesting a widespread uprising in Yorkshire against Norman authority.

This combined Anglo-Danish army advanced on York, the most important city in northern England. York, at this time, was defended by two Norman castles, a testament to William’s efforts to secure the region. However, these defenses proved inadequate against the size and determination of the rebel force. In a decisive battle, the Anglo-Danish army defeated the Norman garrison and captured the city.

William’s Response

News of the fall of York and the Danish invasion reached William while he was in the Forest of Dean. The king immediately recognized the severity of the threat and marched north with his army. The speed of William’s response caught the rebels off guard, and upon learning of his approach, the Danes abandoned York, either retreating to their ships or establishing defensive positions along the rivers Humber, Aire, and Ouse.

William’s campaign to reclaim the north was swift and brutal. By Christmas of 1069, he had reoccupied York and begun a systematic devastation of the northern counties known as the Harrying of the North. This scorched earth policy was designed to deprive the rebels and their Danish allies of resources and to punish the local population for their support of the uprising.

The Harrying of the North

The Harrying of the North stands as one of the most controversial episodes of William’s reign. Contemporary chroniclers describe it as an act of unrestrained fury, with William making “no effort to restrain his fury” as he ordered the destruction of crops, livestock, and even entire villages and their inhabitants.

It is estimated that over 100,000 people – over a quarter of the population of the North of England – were slaughtered or died from starvation during the Normans’ savage reprisals.

The motivations behind this brutal campaign were twofold. Firstly, it served a strategic purpose by denying resources to the Danish army and any potential future invasions. William of Malmesbury, a 12th-century historian, explains that by destroying everything, the king ensured there would be nothing to sustain an enemy force.

Secondly, the Harrying was an act of vengeance. William had lost hundreds, perhaps thousands, of his soldiers in the northern rebellions, particularly in Durham and York. The scale of the destruction was intended to serve as a stark warning against future resistance.

Consequences of the Invasion

The immediate consequence of the Danish invasion and the subsequent Harrying of the North was widespread devastation in northern England. The region, which had been one of the most prosperous parts of the country, was reduced to a wasteland. The Domesday Book, compiled nearly two decades later, still recorded much of Yorkshire as “waste,” a testament to the long-lasting impact of William’s punitive campaign.

For the Danes, the invasion ultimately proved futile. Despite their initial success in capturing York, they were unable to maintain their position in the face of William’s counterattack. The Norman king, recognizing the threat posed by continued Danish involvement, resorted to bribery. He offered the Danish leaders a substantial payment and permission to plunder the eastern coast in exchange for their departure the following spring.

This agreement effectively ended the Danish intervention in England. While it allowed William to focus on suppressing the remaining English resistance, it also highlighted the precariousness of his position. The need to buy off the Danes demonstrated that, even three years after Hastings, Norman control over England was far from secure.

Long-term Impact

The events of 1069-1070 had far-reaching consequences for both England and Denmark.

For England, the failure of the Danish invasion and the brutal suppression of the northern rebellion marked the consolidation of Norman rule. It demonstrated William’s brutal resolve and military capability, and discouraged further large-scale Anglo-Saxon resistance.

The invasion reinforced William’s strategy of castle construction. In the years following 1070, Norman castles proliferated across England, serving as visible symbols of Norman authority and providing strong points for military control.

The Harrying of the North led to significant demographic changes in northern England. Many areas saw a sharp decline in population, with some regions taking generations to recover. This depopulation facilitated the introduction of Norman landowners and the restructuring of the northern economy.

For the Danes, the failure of the 1069 invasion did not immediately end Danish ambitions in England. Subsequent Danish kings continued to assert their claim to the English throne well into the 13th century. Certainly, the events of 1069-1070 were not the end of Danish involvement in English affairs. In 1075, another large-scale Danish raid was launched, this time in support of the Revolt of the Earls. This rebellion, led by English and Norman nobles against William’s rule, saw the Danish force ravage the Lincolnshire coast and York.

However, the most significant Danish threat came a decade later. In 1085, Cnut IV of Denmark, who had participated in both the 1069 and 1075 attacks, planned a massive invasion of England. He assembled an alliance with Robert I, Count of Flanders, and Olaf III of Norway, gathering a fleet that reportedly numbered 1,660 ships.

William’s response to this threat was comprehensive. He brought over large numbers of mercenaries from the continent, stationing them not just in coastal areas but as far inland as Worcester. Some sources even claim that William ordered coastal districts to be laid waste to deny resources to potential invaders, though evidence for this is limited.

Ultimately, the planned invasion of 1085-1086 never materialized. Cnut’s attention was diverted by internal problems in Denmark, and he was killed by rebels in July 1086. His death marked the end of the last serious Danish threat to England.