The Mongol capture of Beijing (Zhongdu) in 1214–1215 marked a pivotal moment in Genghis Khan’s campaign to dismantle the Jin dynasty, a conflict that reshaped East Asian history. This brutal siege exemplified the Mongols’ evolving military tactics and their capacity to adapt to fortified urban warfare, while also underscoring the catastrophic human toll of their conquests.

Background: The Jin-Mongol Rivalry

By the early 13th century, the Jin dynasty – a Jurchen-led regime controlling northern China – had grown complacent, dismissing the Mongols as “illiterate nomads”. Tensions escalated in 1210 when the Jin emperor demanded Genghis Khan’s submission. The Mongol leader, insulted, vowed retaliation. After securing his western flank by subjugating the Tangut kingdom of Xi Xia (Western Xia) in 1209–1210, Genghis turned his full attention to the Jin.

The Jin’s northern capital, Zhongdu (modern Beijing), was a symbol of imperial power, protected by high walls and defended by gunpowder weapons, molten metals, and boiling oils. Yet the Mongols, masters of mobile cavalry warfare, were undeterred.

Initial Assaults and Strategic Maneuvers

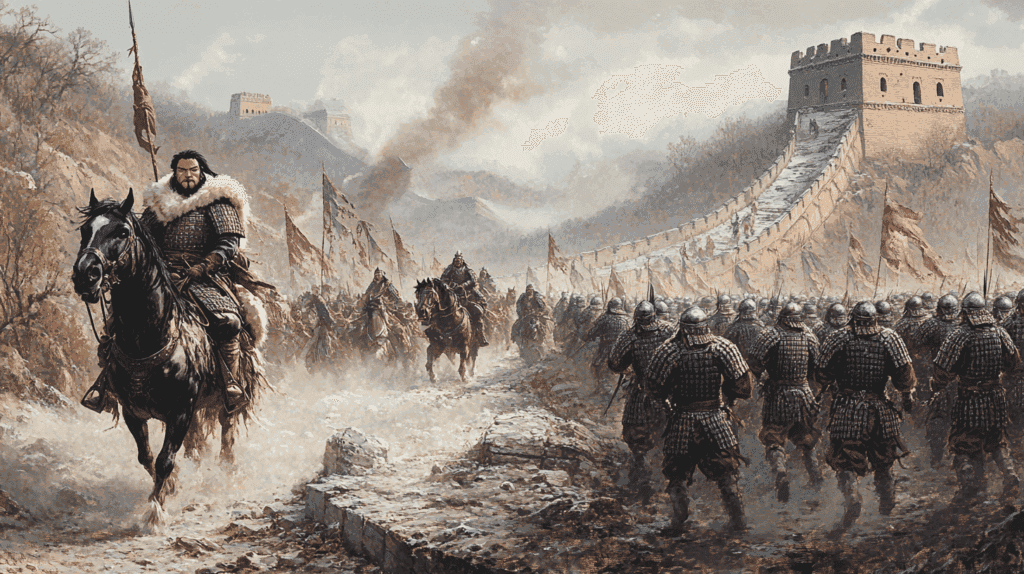

In 1211, after breaching the Great Wall through a combination of deception and tactical alliances – including the defection of the Ongut tribe guarding its western edge – Genghis Khan’s forces swept into northern China. The Mongols first lured Jin troops into fatal ambushes at critical passes like Juyongguan by feigning retreats, then exploited gaps in defenses created by political miscalculations.

The Jin emperor’s decision to relocate his court south to Kaifeng in 1214 left Beijing vulnerable, with its garrison demoralized and supply lines stretched. By early 1215, the Mongols had isolated the city, cutting off relief convoys and trapping nearly one million civilians and soldiers inside, but its formidable defenses stalled their advance.

Beijing’s fortifications presented a daunting challenge:

- Nine miles of walls up to 40 feet high, protected by 900 watchtowers and a 30-foot-deep moat.

- Advanced weaponry including double- and triple-armed ballistae, trebuchets launching incendiary clay pots, and a primitive poison gas system. The latter involved wax-sealed projectiles packed with toxic herbs, human waste, and gunpowder, which released lethal fumes upon detonation.

- Boiling oil and firebombs dropped from walls to incinerate attackers.

The Mongols’ initial frontal assaults faltered against these defenses. Ladder teams were incinerated by firebombs, while siege engines pushed forward by Jin prisoners – used as human shields – collapsed under concentrated crossbow volleys. Attempts to tunnel under walls using cowhide-covered trenches failed when the Jin dropped incendiary bombs, obliterating entire squads.

Siege Tactics and Stalemate

Genghis shifted to a war of attrition, blockading the city while deploying psychological tactics:

- Forced labor: Jin captives repaired Mongol siege equipment and absorbed Jin defenders’ arrows, creating moral dilemmas for soldiers targeting their own people.

- Resource denial: Mongol cavalry intercepted two critical food convoys, exacerbating starvation.

- Technological adaptation: The Mongols reverse-engineered captured Jin artillery, deploying trebuchets to bombard the city with debris and disease-ridden corpses.

By winter 1214–1215, conditions inside Beijing deteriorated catastrophically. Chroniclers describe streets filled with emaciated corpses, cannibalism among desperate residents, and mass suicides by families preferring death to Mongol captivity

The Final Assault

In June 1215, after the Jin commander fled the city (and was later executed by the emperor), Beijing’s defenses collapsed. The Mongols exploited this leadership vacuum:

- Breaching the walls: Demoralized defenders abandoned their posts, allowing Mongol troops to scale under-manned sections.

- Urban combat: Once inside, the Mongols systematically cleared neighborhoods, using captured Jin soldiers to identify holdout positions.

- Destruction of resistance: Any organized defense dissolved as Mongol heavy cavalry charged through narrow streets, crushing any opposition.

As Mongol troops stormed Zhongdu, they unleashed a month-long rampage. Contemporary accounts depict streets “slippery with human fat” and mountains of bones outside the walls.

Military Evolution and Tactical Adaptation

The siege highlighted the Mongols’ ability to assimilate new warfare techniques:

- Siegecraft: Initially reliant on cavalry, they adopted Chinese engineering strategies, including siege towers and catapults.

- Logistical Mastery: By cutting supply lines and intercepting Jin relief convoys, they crippled the city’s resilience.

- Psychological Terror: Massacres and systematic destruction demoralized enemies, a tactic later refined in campaigns like Baghdad (1258).

Human and Cultural Devastation

The fall of Zhongdu precipitated a demographic catastrophe:

- Massacres: Tens of thousands were slaughtered, with reports of girls leaping from walls to avoid capture.

- Plague and Famine: The siege’s aftermath saw outbreaks of disease exacerbated by Mongol biological warfare.

- Cultural Erasure: Libraries, palaces, and infrastructure were razed, erasing centuries of Jin cultural achievements.

Northern China’s population plummeted from 50 million in 1195 to 8.5 million by 1236, a decline attributed to war, famine, and displacement.

Legacy of the Siege

Zhongdu’s capture (renamed Dadu in 1272) became an administrative hub for Yuan dynasty China, while the Jin dynasty, stripped of its northern territories, limped on until its final destruction in 1234. The campaign in China demonstrated the Mongols’ capacity to conquer sophisticated urban centers, foreshadowing their expansion into Persia, Russia, and Eastern Europe.

The 1214–1215 siege of Beijing marked a turning point in Eurasian history. Genghis Khan’s victory shattered the myth of Jin invincibility, paving the way for the Mongols’ eventual domination of China under Kublai Khan. Yet the human cost was staggering, with scholars debating whether the campaign constituted one of history’s first genocides.

In the end, the fall of Beijing underscored a grim reality of Mongol conquest: their unmatched ability to blend innovation, brutality, and strategic patience – a formula that would forge the largest contiguous empire in history.