In the shadow of endless northern forests, between rivers that carve through what would one day be Russia, a small band of Norsemen kindled fires in the year 825. They came not as raiders this time, but as settlers – forging what would become the cradle of the first Russian state. Their settlement, known to them as Holmgard, and to later Slavic and Byzantine chroniclers as Novgorod, would emerge as one of the most influential hubs of trade, power, and cultural fusion in the medieval world.

The World in 825 AD

By the early ninth century, Europe was being reshaped by the ceaseless momentum of the Viking Age. To the west, the Norse struck monasteries on Lindisfarne and Iona; to the south, they sailed up the Seine and threatened the Frankish heartlands; to the north, they consolidated kingdoms in Scandinavia. But another direction called to them – east, across the Baltic and into the rich riverlands of the Slavs.

Here lay not the promise of plunder, but profit. The lands that stretched between the Baltic Sea and the Black Sea formed a vast network of lakes and rivers – a natural trade route between northern Europe and the glittering empires of the south. Byzantine Constantinople, with its gold and silks, Arab Caliphates with their silver dinars, and the steppe nomads with their captured slaves – all were connected by the waterways that wound through what is now Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine.

It was along these rivers that the Norse – known in these lands as the Varangians – found their destiny.

The Arrival of the Varangians

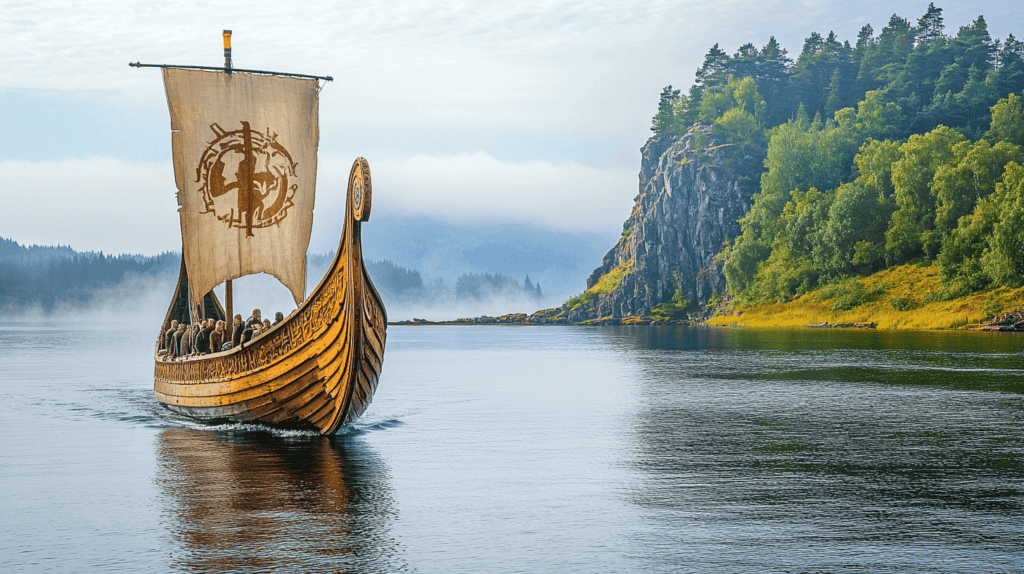

The Primary Chronicle, the legendary source of early Rus’ history compiled centuries later, tells that Scandinavian traders and warriors first arrived in Slavic lands seeking tribute and trade. Their longships cut through the Ladoga Lake and the Volkhov River, leading them deeper into the eastern forests.

Around 825, these Norse adventurers established a permanent foothold on the Volkhov near Lake Ilmen – a site ideally positioned for commerce between the Baltic and the deep river arteries that led south to the Dnieper and the Volga. They named their settlement Holmgard, roughly “island enclosure,” likely referring to its position on a fortified height amid waterways.

To later generations, Holmgard became Novgorod – the “new town.”

These early settlers were not isolated foreigners. They interacted constantly with the Slavic tribes – the Ilmen Slavs, the Chud, the Merya, and the Krivichs – who already inhabited the region. Over time, Norsemen took local wives, adopted Slavic customs, and began to blend two cultures into something entirely new: the Rus’.

Norsemen Beyond the Seas: From Raiders to Rulers

The Vikings who came east were mostly Swedish in origin, hailing from the Mälaren region, particularly Birka and Uppland. While their Danish and Norwegian kin sailed toward the British Isles and Carolingian lands, these Swedes – the Rus’ people – followed the eastern rivers in search of trade with Byzantium and the Caliphate.

Their journeys were perilous but immensely profitable. Furs from the Arctic forests, slaves from Slavic villages, honey, wax, and amber flowed southward. In return came silver dirhams from Islamic merchants, which have been found by the thousands in Scandinavian hoards. Many bear Arabic inscriptions, silent witnesses to the astonishing connectivity of the early medieval world.

Novgorod, by virtue of its geography, became the lynchpin of that system. From there, the route “from the Varangians to the Greeks” – the ancient trade path linking the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea – could be controlled and taxed. Those who controlled Novgorod controlled the arteries of commerce that fed the entire Rus’ domain.

The Making of a Trading Power

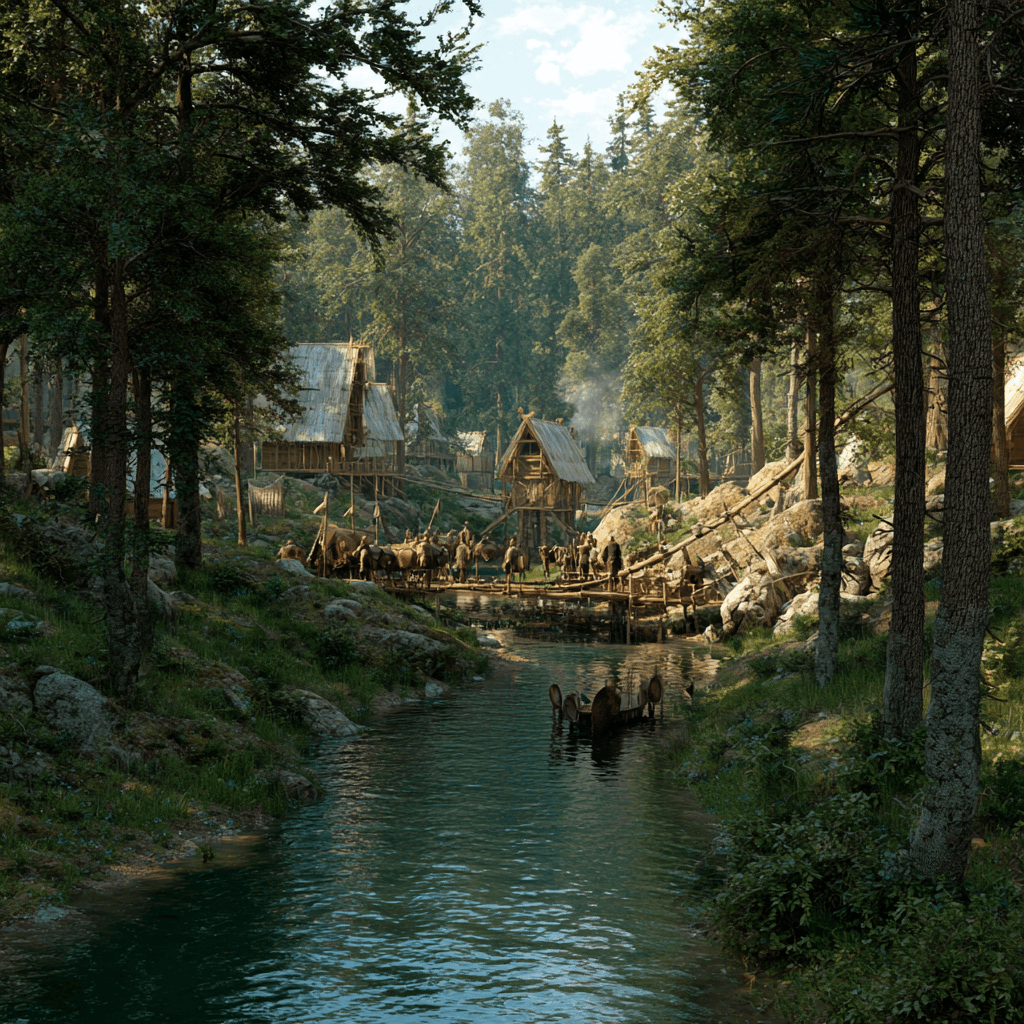

The Viking settlement in Novgorod rapidly evolved from a military outpost to a thriving hub of trade. Archaeological evidence from the site shows that by the mid-ninth century, there existed a well-organized community with urban features: wooden streets, workshops, fortified walls, and dwellings built in Scandinavian style.

The finds at Rurikovo Gorodische – a fortified hill near modern Novgorod – have revealed remnants of early Varangian presence. Coins, scales, and weights speak to the intensity of trade. Burials with Scandinavian grave goods, including swords and brooches, attest to the Norse influence.

But as the settlement grew, it also became multicultural. Finnic and Slavic artisans, merchants, and farmers joined the Norse colonists. Over time, governance transitioned from being purely Viking to a hybridized form of rule. The leaders, or “konungs,” of the Varangians would come to be recognized as princes – kniazes – ruling over both Norse and Slavic subjects.

This fusion of peoples, Scandinavian adventurers and Eastern Slavs, was the seed from which the Kievan Rus’ would eventually grow.

Rurik and the Rise of the Rus’

Although the exact date of Rurik’s arrival is debated, many chronicles place it around 862, his origins lie in this earlier generation of Norse settlement. The warriors who had founded Holmgard-Novgorod in 825 had paved the way for figures like him.

Rurik, a Varangian chieftain of noble lineage, was invited, according to the Chronicle, by the local tribes to bring “order” to their land after years of internecine strife. Whether this “invitation” was historical or political propaganda, the outcome was decisive: under Rurik and his successors, Novgorod became the nucleus of the first organized Rus’ state.

The polity that emerged was deeply shaped by its Viking foundations. Its military elite remained Scandinavian in style for generations: their weapons, tactics, and burial rites clearly identifiable as Norse. Yet, the ruling dynasty quickly adopted Slavic language, customs, and Orthodox Christianity following later conversion.

Thus, what began in 825 as a small Norse trade base in the woods became, within a century, the northern citadel of one of medieval Europe’s most sophisticated and influential states.

Commerce, Culture, and Conflict

Novgorod’s position at the crossroads of trade brought both wealth and challenge. The Varangians needed to secure the rivers from hostile tribes and rival chieftains. To the south, the Khazars – a powerful Turkic people – dominated the Volga region and taxed merchants. To the west were the Balts; to the north, the Finnic tribes who guarded their lands jealously.

Archaeological and written sources suggest that the early inhabitants of Novgorod maintained a formidable warrior culture. Their longships patrolled the Volkhov, and their axes and swords were used not only for plunder but for law enforcement and escorting merchant fleets.

At the same time, Novgorod became a point of cultural transmission. Norse rune stones in Sweden speak of men who “went east” and “held the fortress at Holmgard.” Some never returned. Others came back laden with gold, tales of Byzantine cities, and exotic goods. From Novgorod, Northern Europe learned of distant Constantinople – “Miklagard,” the Great City – and of the dazzling riches of the south.

It was through these eastern ventures that Scandinavians began to shift from pagan isolation to broader participation in the Christian world. The seeds of cultural transformation lay hidden in their trade routes.

A Meeting of Worlds

The Norse establishment at Novgorod was a confluence of civilizations. Varying linguistic, religious, and artistic traditions met and merged here.

The Norsemen brought with them their gods – Odin, Thor, and Frey – as well as their distinctive art styles: interlaced beasts, gripping beasts, geometric designs that later appeared on local jewelry and weapon ornamentation. The Slavs contributed their agricultural base, folk traditions, and pagan pantheon centered on Perun, the thunder god, who would one day be replaced in veneration by Saint Elijah after Christianization.

These interactions produced a unique hybrid culture visible in both material and spiritual life. The architecture of early Novgorod incorporated both Scandinavian timber-building techniques and local styles. Decorative art found in graves shows designs blending both Nordic and steppe motifs. Even names in the chronicles – Igor (from the Norse Ingvarr), Olga (from Helga), Oleg (from Helgi) – bear witness to this synthesis.

In Novgorod’s multicultural crucible, the Norse ceased to be mere outsiders. They became founders.

The Geography That Made an Empire

Why Novgorod, among so many forested riverlands, succeeded where others failed owes much to geography. The Volkhov River connects directly to Lake Ilmen, offering a navigable link between the Baltic and interior Russia.

From here, routes branched south to the Dnieper, eventually reaching Kiev and the Black Sea, and eastward to the Volga, leading to the Caspian. These rivers were medieval highways, and controlling them meant commanding the flow of goods, information, and people.

Moreover, Novgorod occupied a defensible position. Surrounded by marshes and forests, it could be fortified easily. It was also far enough north to avoid the constant raids of steppe nomads that plagued southern cities.

The city’s natural moat, the icy rivers and lakes, became both protection and commerce routes. In winter, when the waterways froze, they transformed into highways of trade over ice. In summer, fleets of longships threaded through the same channels, their sails glinting in the northern sun.

Archaeology and the Echoes of the Past

Modern excavations have illuminated much about the early settlement that emerged in 825. Layers of earthen ramparts, wooden causeways, and artifacts unearthed from Rurikovo Gorodische display the evolution from a trading post to an urban stronghold.

Finds include:

- Scandinavian-style swords and spearheads

- Scales, weights, and imported silver coins, evidence of far-reaching trade

- Amber amulets and religious pendants showing both Norse and Slavic motifs

- Early Christian crosses, signaling contact with Byzantium even before official conversion

The density of settlement layers suggests continuous habitation from the early ninth century onward: confirming the endurance of that first Varangian foothold.

Runestones back in Sweden corroborate this connection. In Uppland and Södermanland, inscriptions commemorate men who “died in Holmgard” or “served the king in Garðaríki” – the Old Norse term for the land of cities, meaning Rus’.

These stones are epitaphs for the explorers who helped bridge two worlds, and whose exploits would echo through the chronicles and sagas for centuries to come.

The Path Toward Kievan Rus’

The establishment of Novgorod was the prelude to a grander political story: the formation of the Kievan Rus’, the first East Slavic state.

By the mid-ninth century, the Varangian rulers of Novgorod extended their influence southward to Kiev, another crucial river port. Whether by conquest or alliance, Novgorod’s princes came to dominate much of the region’s trade network. The state that emerged – centered on the Dnieper but rooted in the northern forests – blended Scandinavian leadership with Slavic population and Byzantine inspiration.

The Rus’ princes maintained contacts with Constantinople, signing trade treaties and even serving as mercenaries in the emperor’s elite Varangian Guard. Their strength rested not only on war but on control of commerce – the same formula that had brought life to Novgorod in 825.

Over time, Kiev eclipsed Novgorod in political centrality, but Novgorod preserved its autonomy and commercial might. It would remain a fiercely independent republic into the late medieval period, centuries after other Rus’ principalities succumbed to Mongol domination.

The foundation stone for that resilience was laid by the Varangian traders who built their wooden halls along the Volkhov. Their legacy was not one of mere conquest, but of transformation. In fusing Norse tenacity with Slavic depth, they gave rise to one of the most remarkable cultural syntheses in medieval history – the genesis of Russia’s northern soul. And it all began in 825, when Viking longships moored on the Volkhov River and the fires of Holmgard burned for the first time against the dark of the northern woods.