The emergence of the Kingdom of León in the early 10th century marked a pivotal moment in the history of the Iberian Peninsula, shaping the course of the Christian reconquest and laying the foundations for the future Kingdom of Spain. This period, from 910 to 930 CE, witnessed the transformation of a frontier region into a powerful Christian kingdom that would play a crucial role in the centuries-long struggle against Muslim rule in Iberia.

The Foundation of León (910 CE)

The Kingdom of León was born in 910 CE when García I (910-914) inherited the western portion of his father’s realm. Alfonso III, known as Alfonso the Great, had divided his kingdom among his three sons, a decision that would have far-reaching consequences for the political landscape of Christian Iberia.

García I’s first significant act was to move the capital from Oviedo, the longtime seat of Asturian power, to the city of León. This strategic relocation reflected the changing realities of the Christian kingdoms in northern Iberia. As the frontier of Christian control had gradually pushed southward, León’s more central location offered better access to newly conquered territories and provided a stronger base for further expansion.

The city of León itself had a rich history dating back to Roman times. Founded as a permanent camp for the Legio VI Victrix around 29 BC, it later became the base for the Legio VII Gemina in 74 AD. This Roman legacy provided León with strong fortifications and a strategic location, making it an ideal choice for the new capital of the emerging kingdom.

Early Challenges and Consolidation

The early years of the Kingdom of León were marked by both opportunities and challenges. The Christian kingdoms of northern Iberia were still relatively weak compared to the powerful Umayyad Caliphate to the south. However, the apparent weakness of Islamic Spain at this time encouraged the northward expansion of Christian rule.

García I’s reign was short-lived, lasting only from 910 to 914. Despite its brevity, his decision to establish León as the new capital set the stage for the kingdom’s future growth and importance. Upon García’s death, his brother Ordoño II (914-924) ascended to the throne.

The Reign of Ordoño II (914-924)

Ordoño II’s reign marked a period of significant expansion and military activity for the young Kingdom of León. A skilled military leader, Ordoño launched daring expeditions deep into Muslim territory, reaching as far south as Seville, Córdoba, and Guadalajara. These campaigns demonstrated the growing military capabilities of the Kingdom of León, disrupted Muslim control in central Iberia and brought wealth and prestige to the Leonese court through plunder and tribute.

Ordoño II’s military successes helped to consolidate León’s position as the leading Christian kingdom in Iberia. His reign also saw the continued development of León as a royal capital, with the construction of new fortifications and the establishment of administrative structures necessary for governing an expanding realm.

Territorial Expansion and the Birth of Castile

During the early 10th century, León expanded its territory to the south and east. One of the most significant areas of expansion was the region that would become known as the County of Burgos, later Castile. This frontier zone was heavily fortified with numerous castles, giving rise to its name “Castilla” (land of castles).

Initially, Burgos remained within the Kingdom of León. However, the seeds of future conflict were sown during this period. The frontier regions, constantly exposed to the threat of Muslim raids, developed a distinct culture and identity. The inhabitants of these areas, hardened by the dangers they faced, were often at odds with the more established traditions and laws of León.

This tension would eventually lead to the emergence of Castile as a separate and powerful entity under the leadership of counts like Fernán González. However, during the period from 910 to 930, Castile remained an integral, if sometimes restive, part of the Leonese realm.

Religious and Cultural Developments

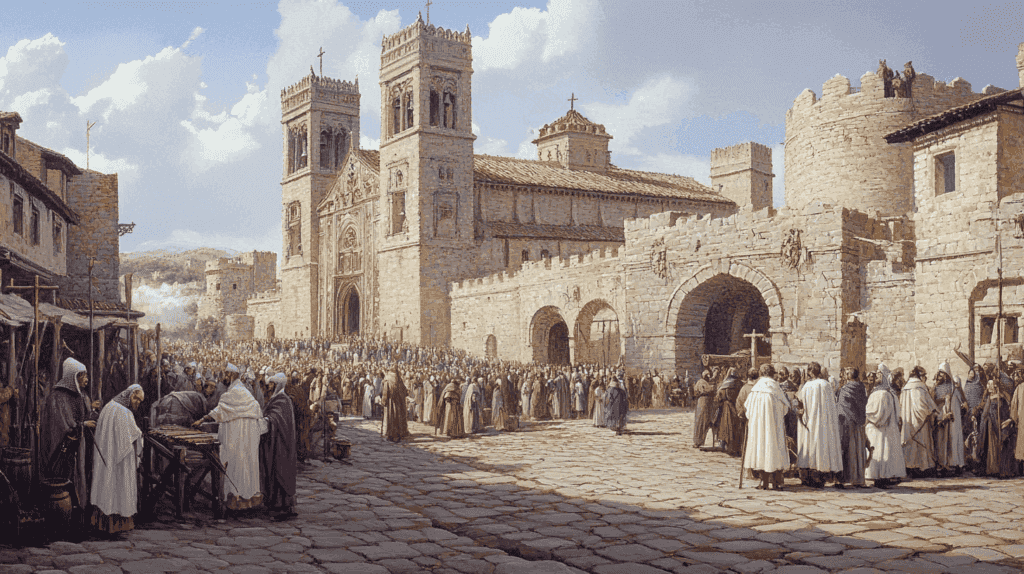

The establishment of León as the capital of a Christian kingdom had significant implications for the religious and cultural life of the region. The city became an important stop on the Camino de Santiago, the pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela. This brought an influx of pilgrims, ideas, and cultural influences from across Europe.

The Leonese monarchs also sought to strengthen their legitimacy through association with the Church. They patronized religious institutions, founded monasteries, and sought to present themselves as defenders of Christianity against Muslim rule. This religious dimension added to the ideological underpinnings of the ongoing Reconquista.

Economic and Social Changes

The emergence of the Kingdom of León brought about significant economic and social changes in the region. The establishment of a royal court in León stimulated urban growth and economic activity. The city became a center of trade and craftsmanship, attracting merchants and artisans from surrounding areas.

The process of repopulation and colonization of newly conquered territories also had profound social implications. The monarchs of León encouraged the settlement of these areas by offering privileges and freedoms to those willing to inhabit the dangerous frontier zones. This policy led to the development of a more diverse and dynamic society, with opportunities for social mobility that were rare in other parts of medieval Europe.

Relations with Neighboring Christian Kingdoms

While the Kingdom of León emerged as the most powerful Christian state in Iberia during this period, it was not without rivals. To the east, the Kingdom of Navarre was also growing in strength. The relationship between León and Navarre was complex, marked by both cooperation against common Muslim enemies and occasional conflicts over territory and influence.

To the west, the County of Portugal, still nominally part of León, was beginning to develop its own distinct identity. While full Portuguese independence was still more than two centuries away, the seeds of this future separation were already being sown during the early years of the Leonese kingdom.

The Threat from Al-Andalus

Despite the growing strength of León and other Christian kingdoms, the threat from Muslim Al-Andalus remained significant. The Umayyad Caliphate, based in Córdoba, was experiencing a period of resurgence under the leadership of Abd al-Rahman III, who became Caliph in 929.

The Christian kingdoms, including León, faced regular raids and incursions from Muslim forces. These attacks served to both check Christian expansion and to bring wealth and slaves back to Al-Andalus. The constant threat from the south helped to shape the militarized society of the Christian kingdoms and provided a unifying purpose for their continued expansion and consolidation.

The Reign of Fruela II and Political Instability

The death of Ordoño II in 924 ushered in a period of political instability for the Kingdom of León. Fruela II, the third son of Alfonso III, succeeded to the throne. However, his reign was short and troubled, lasting only from 924 to 925.

Fruela II’s brief rule was marked by internal conflicts and a lack of significant military achievements against the Muslims. His death in 925 led to a succession crisis that would have long-lasting implications for the kingdom.

Following Fruela II’s death, a complex succession struggle ensued. The main contenders were Alfonso Fróilaz, son of Fruela II, and the sons of Ordoño II: Sancho Ordóñez, Alfonso IV, and Ramiro II.

This period of civil war and political instability lasted for several years, weakening the kingdom’s ability to continue its expansion and resist Muslim incursions. The conflict was eventually resolved in favor of the sons of Ordoño II, but the internal strife had taken its toll on the young kingdom.

The Emergence of Ramiro II and the Battle of Simmancas

By 931, Ramiro II had emerged as the sole ruler of León, marking the end of the succession crisis. His reign, which lasted until 951, would bring stability and military success back to the kingdom. The key moment occured eight years into his reign at Simancas.

The Battle of Simancas, which began on July 19, 939, was a pivotal clash between Christian and Muslim forces on the Iberian Peninsula. This confrontation pitted the King Ramiro II of León against the powerful Umayyad Caliph Abd al-Rahman III near the walls of Simancas, a strategic city along the Duero River.

The conflict originated from Abd al-Rahman III’s ambitious campaign launched in 934 to expand Muslim control northward. The Caliph had amassed a formidable army, reportedly numbering around 80,000 troops, with support from Muhammad ibn Yahya al-Tujibi, the governor of Zaragoza. This force represented the might of the Caliphate of Córdoba, then at the height of its power in the peninsula.

Facing this threat, King Ramiro II assembled a coalition of Christian kingdoms. His army included his own Leonese troops, forces from Castile led by Count Fernán González, and Navarrese soldiers under García Sánchez I. This alliance represented a rare moment of unity among the often-fractious Christian realms of northern Iberia.

The battle commenced with a spectacular and ominous event. Arab chroniclers recorded a terrifying solar eclipse on the first day of fighting, which cast an eerie yellow darkness over the battlefield. This phenomenon struck fear into both Christian and Muslim combatants, many of whom had never witnessed such an occurrence.

Fighting raged for several days, with the terrain around Simancas becoming a bloody arena for the clash of civilizations. The Christian forces, despite being outnumbered, fought with determination to defend their lands and faith. Meanwhile, the Muslim army, confident in its superior numbers and recent victories, sought to break the Christian resistance.

In a surprising turn of events, the Christian alliance emerged victorious. They not only repelled the Muslim invasion but routed the Cordovan forces. This defeat was a significant blow to Abd al-Rahman III, who narrowly escaped capture. The Muslim army’s retreat turned chaotic, with many soldiers fleeing or being captured.

The Battle of Simancas marked a crucial turning point in the Reconquista. It halted the Muslim advance and bolstered Christian morale, proving that the Caliphate was not invincible. This victory allowed the Christian kingdoms to consolidate their positions and eventually push southward. The victory strengthened Ramiro II’s position and highlighted the importance of Christian unity against the Muslim threat.

Long-term Significance

The emergence of the Kingdom of León had profound and lasting effects on the history of the Iberian Peninsula. It established León as the primary Christian power in Iberia, a position it would hold for over two centuries. The kingdom would play a crucial role in the early stages of the Reconquista, pushing the frontier of Christian control southward. The political structures developed during this period laid the groundwork for the later Kingdom of Castile and León, which would eventually evolve into the Kingdom of Spain.