The Black Death, a catastrophic plague that swept through Europe from 1347 to 1351, stands as one of the most devastating pandemics in human history. This outbreak of bubonic plague claimed the lives of an estimated 25 million people in Europe alone, with some estimates suggesting that up to half of the continent’s population perished. The pandemic’s impact was so profound that it reshaped the social, economic, and cultural landscape of medieval Europe, leaving an indelible mark on the course of history.

Origins and Spread

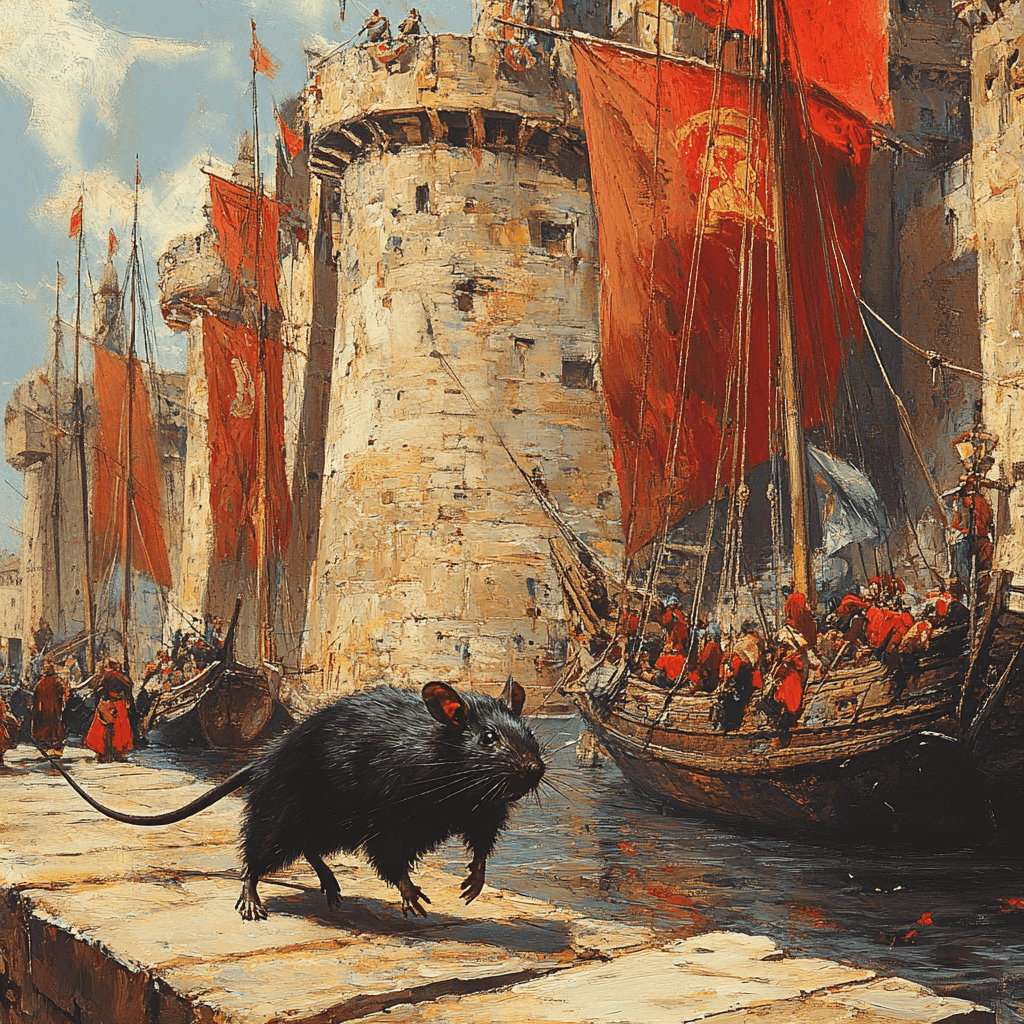

The Black Death is believed to have originated in Central Asia before making its way to Europe through trade routes. The disease, caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, was primarily spread by fleas living on rats that were common passengers on merchant ships. As these vessels docked at various ports across the Mediterranean and beyond, they unwittingly brought with them the deadly plague.

The first recorded outbreak in Europe occurred in 1347 when Genoese trading ships docked at the Sicilian port of Messina. From there, the disease spread rapidly across the continent, reaching England by 1348 and Scandinavia by 1350. The speed at which the plague traveled and the horrific symptoms it inflicted upon its victims created an atmosphere of terror and despair throughout Europe.

Symptoms and Mortality

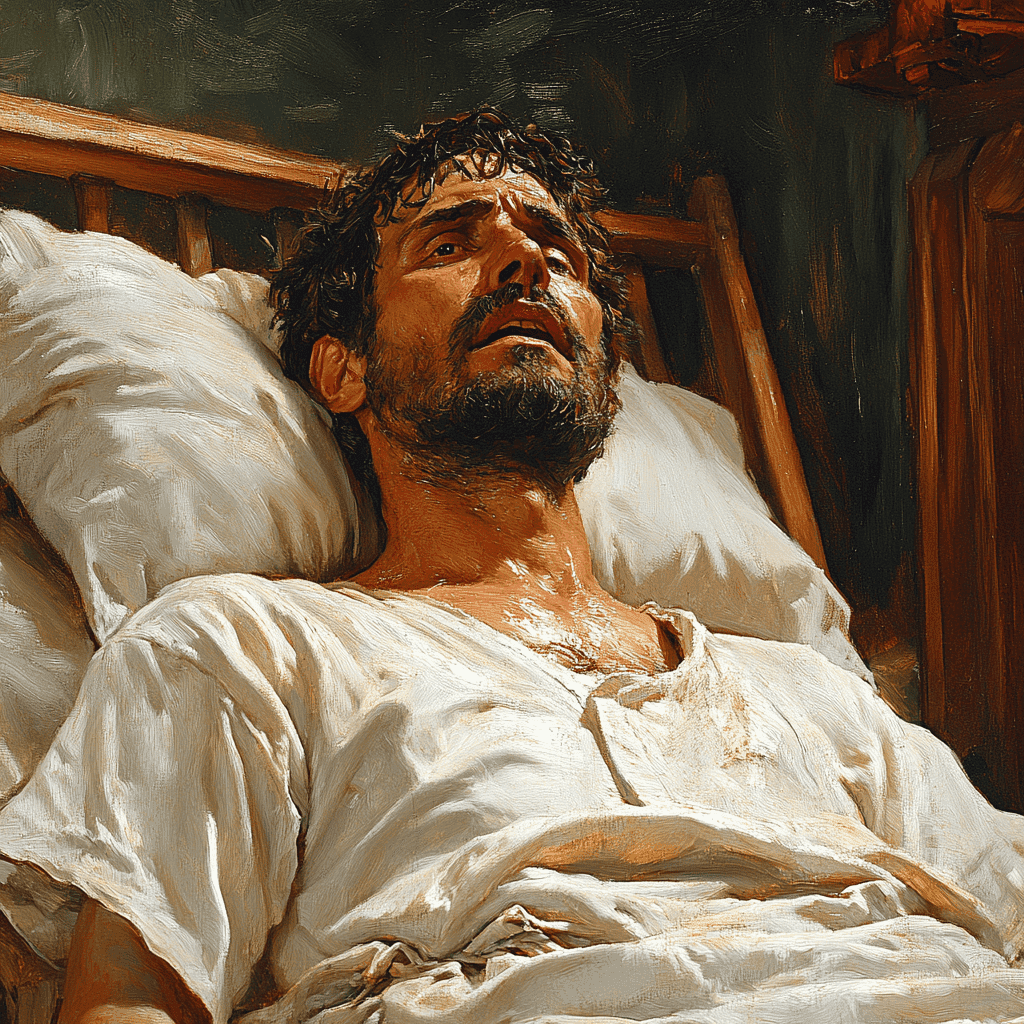

The most common form of the plague during the Black Death was bubonic plague, characterized by the appearance of swollen, painful lymph nodes called buboes. Other symptoms included high fever, muscle aches, and fatigue. In many cases, the disease progressed to septicemic or pneumonic plague, which were even more deadly and contagious.

The mortality rate of the Black Death was staggering. In some areas, up to 60% of the population succumbed to the disease. The sheer number of deaths overwhelmed medieval society’s ability to cope. Bodies piled up in the streets, and mass graves became commonplace. The scale of the devastation was unprecedented, leaving survivors traumatized and struggling to make sense of the calamity that had befallen them.

In England official records from the time show how great the horror could be at a local level. For example, a village on an estate in Cambridgeshire lost 70% of its tenants in just a few months in 1349, according to manorial rolls, while the village of Quob in Hampshire was completely wiped out by the plague. In Florence, Italy, tax records from before and after the Black Death suggest that around 60-70% of the city’s population perished in 1348. With death on this scale, the bodies of plague victims piled up in the street waiting for burial.

A Sudden Labor Shortage

The Black Death had far-reaching consequences for European society and economy. The massive reduction in population led to significant changes in the labor market and social structures.

With so many workers dead, labor became a scarce and valuable commodity. This scarcity led to a significant increase in wages for both skilled artisans and unskilled laborers. The shortage of agricultural workers forced landowners to offer better terms to peasants to keep them on their lands, including substituting wages or money rents for traditional labor services.

Real Estate Crash

The high mortality rate resulted in the fragmentation of large estates, as properties were inherited by multiple survivors. This fragmentation, combined with the partible inheritance system common in many parts of Europe, led to an unusual abundance of property on the market. The combination of higher wages and more accessible property allowed a larger portion of the population to acquire land and wealth, contributing to increased social mobility.

Economic Disruption

In the short term, the Black Death caused severe economic disruption. Trade suffered as fear of contagion led to the abandonment of many commercial activities. The scarcity of goods and labor resulted in rapid inflation, with prices for both locally produced and imported goods skyrocketing.

While the immediate economic impact was devastating, some historians argue that the Black Death had some positive long-term economic effects. The reorganization of agrarian production towards greater efficiency and the establishment of a new high-mortality, high-income equilibrium may have set the stage for faster economic development in subsequent centuries.

The Church is Helpless

The failure of prayer and religious institutions to prevent or cure the plague led to a crisis of faith for many Europeans. Some responded by intensifying their religious devotion, while others began to question the authority of the Church. This shift in religious attitudes contributed to the eventual weakening of the Catholic Church’s monopoly on spiritual matters and may have played a role in setting the stage for the later Protestant Reformation.

The Flagellant Movement

One extreme phenomenon that emerged during the Black Death of 1349 was that of Christians seeking extreme measures to atone for their sins and appease what they believed to be God’s wrath. The Flagellant movement began in Eastern Europe, around Hungary and Poland, before spreading to Germany, modern-day Belgium, and the Netherlands in 1348. Groups of Flagellants, typically numbering between 200 and 300 individuals (though sometimes reaching up to a thousand), traveled from town to town, engaging in public displays of self-flagellation.

These Flagellants practices were rooted in the Christian tradition of penance and the imitation of Christ’s suffering, but taken to extreme levels. Twice daily, they would proceed to public squares or principal churches, where they would remove their shoes and strip to the waist. Forming large circles, they would prostrate themselves on the ground, assuming positions that indicated the nature of the sins they sought to expiate. Armed with scourges featuring three tails, often embedded with sharp nails, they would then take turns flogging each other until blood flowed.

However, the movement quickly became a source of concern for both secular and religious authorities. The Flagellant movement’s growing popularity, and increasingly radical beliefs led Pope Clement VI to officially condemn them in a bull issued on October 20, 1349.

The Plague Doesn’t Take Sides

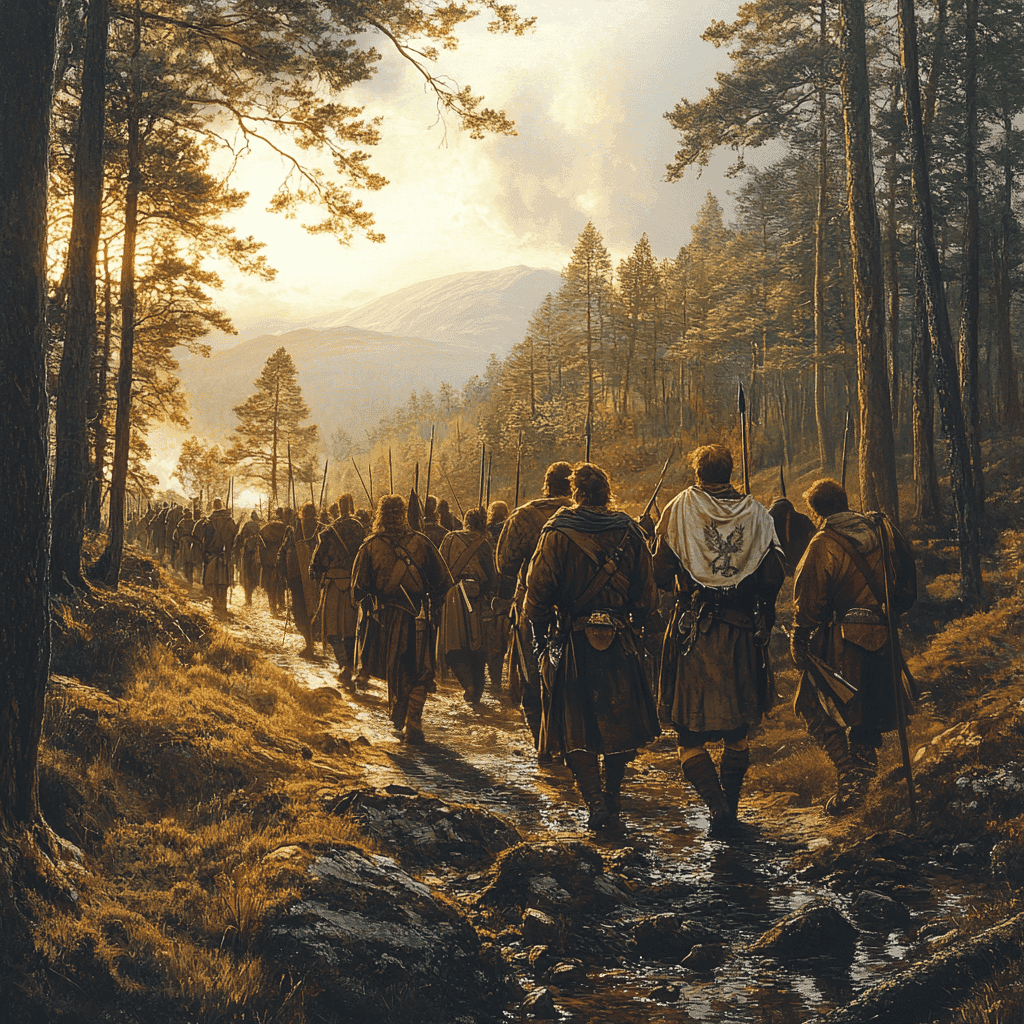

In the autumn of 1349, as the Black Death ravaged England, a grim tale of hubris and tragedy unfolded along the Anglo-Scottish border. The Scots, hearing of the devastating plague afflicting their southern neighbors, saw an opportunity to exploit England’s weakness. They believed that the English had incurred divine wrath, interpreting the plague as God’s vengeance upon their long-standing enemies.

Emboldened by their perceived divine protection, the Scottish forces gathered in the forest of Selkirk. Their ambitious plan was nothing short of a full-scale invasion of England, aiming to conquer the realm while it was weakened by disease and death.

However, the Scots’ confidence was tragically misplaced. As they prepared to march south, the “fierce mortality” that had decimated England suddenly struck their ranks. The plague, indiscriminate in its victims, began to spread rapidly through the Scottish army.

The scene in the Selkirk forest quickly transformed from one of military preparation to one of horror and despair. Within a short span of time, the Scottish army was decimated. Henry Knighton, the English chronicler, reported that around 5,000 Scots perished in this ill-fated gathering. Instead of marching triumphantly into England, the survivors retreated in disarray back to their homeland.

But the tragedy did not end with their retreat. Unknowingly, the surviving soldiers carried more than their weapons and wounded pride back to Scotland. Their baggage and bodies harbored the deadly plague, ensuring its spread northward. As autumn turned to winter in 1349, the retreating army became unwitting agents of the very calamity they had mocked. The country that had believed itself spared from God’s wrath now faced the full fury of the Black Death. By spring 1350, the disease had taken hold, spreading with terrifying speed across the Scottish lowlands and highlands alike.

Two Centuries to Recover

The population losses caused by the Black Death were so severe that it took Europe nearly two centuries to regain its pre-plague population levels. This slow recovery had profound implications for European society, economy, and culture.

The aftermath of the Black Death contributed to a shift in Europe’s economic center of gravity. Some regions, particularly in Northwestern Europe, recovered more quickly and began to gain economic and political prominence. This shift would play a role in the later rise of Atlantic powers like England and the Netherlands.

Some scholars argue that the Black Death may have indirectly contributed to the “Great Divergence” – the process by which Europe eventually overtook other world regions in terms of economic and technological development. The social and economic changes catalyzed by the plague may have set the stage for later European advancements.

Conclusion

The Black Death of 1347-1351 was more than just a medical catastrophe; it was a transformative event that reshaped the trajectory of European history. Its impact touched every aspect of medieval life. While the immediate consequences of the Black Death were undoubtedly tragic, causing immense suffering and loss of life, the long-term effects were complex and multifaceted. The plague acted as a catalyst for change, accelerating processes that were already underway and setting in motion new developments that would shape the future of Europe and, by extension, the world.