Introduction

For over six centuries, two ancient superpowers the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) and Persian (Sasanian) Empires clashed in a series of titanic struggles that shaped the fate of the ancient world. Their final, devastating phase – the war of 602-628 – would leave both empires exhausted and vulnerable, paving the way for the rapid rise of Islam and the transformation of the Middle East.

Origins: Rivals at the Edge of Empire

The origins of the Roman-Persian conflict stretch back to the days of the Roman Republic, but it was with the rise of the Sasanian dynasty in Persia (224 CE) that the rivalry reached its zenith. The Sasanians, heirs to the ancient Achaemenids, sought to restore Persian greatness, while the Byzantines viewed themselves as the legitimate successors of Rome, destined to rule the world.

The two empires were natural rivals, divided by geography and religion – Zoroastrian Persia to the east, Christian Byzantium to the west. Their frontiers met in the rich and contested lands of Mesopotamia, Armenia, and the Caucasus, regions that would see repeated invasions and shifting allegiances.

War Erupts Again (502)

In 502 the Persian King Kavadh I, seeking tribute and advantage, invaded Byzantine territory after the Byzantines refused his demands. The initial campaigns saw the Persians capture the key city of Amida, but the Byzantines, under Emperor Anastasius I, eventually managed to recover some ground.

With the accession of Justinian I in 527, the Byzantine Empire entered a period of ambitious expansion and reform. However, Justinian’s dreams of a restored Roman Empire were threatened by the Sasanian menace in the east. The so-called Iberian War (527–531) was sparked by the defection of the Christian kingdom of Iberia (modern Georgia) to Byzantium, provoking Sasanian retaliation.

One of the most celebrated clashes of the era was the Battle of Dara in 530. The Byzantine general Belisarius, though outnumbered, used brilliant tactics and defensive fortifications to rout a much larger Persian force. The Persians, led by General Perozes, suffered over 8,000 casualties, while the Byzantines lost fewer than 5,000 men. This victory boosted Byzantine morale and cemented Belisarius’s reputation as a military genius.

Despite such triumphs, neither side could secure a decisive advantage. The war ended with the “Eternal Peace” in 532, largely because both empires were exhausted and Justinian needed to focus on his campaigns in the West. The treaty required Byzantium to pay Persia a hefty sum in gold, a price for temporary peace.

The Rise of Khosrow I and Renewed Conflict (540–562)

The “Eternal Peace” proved fleeting. In 540, Khosrow I (Chosroes), one of Persia’s greatest rulers, accused Justinian of treaty violations and invaded Byzantine Syria. Khosrow’s campaigns were ruthless: he sacked cities such as Hierapolis, Apamea, and Aleppo, and in 540, he stormed Antioch, massacring many and deporting thousands to Persia.

Belisarius returned to the east but was unable to decisively check Khosrow, who retreated with vast spoils. The two empires settled into a pattern of raids and counter-raids, unable to hold enemy territory for long.

A major theater of conflict was the region of Lazica (modern Georgia), strategically vital for access to the Black Sea and the Caucasus passes. The Lazic War dragged on for two decades, with both empires vying for influence over the local rulers. The mountainous terrain, local resistance, and shifting alliances made the war particularly grueling.

The war ended inconclusively in 562 with the Fifty-Year Peace Treaty. Byzantium agreed to pay annual tribute to Persia in exchange for recognition of Lazica as a Byzantine vassal. The result was a costly stalemate, with neither side achieving lasting gains.

Renewed Hostilities: The War of 572–591

The Fifty-Year Peace Treaty lasted just ten years until 572 when Justin II, Justinian’s successor, refused to continue paying tribute to Persia and declared war. The initial campaigns went badly for the Byzantines: the Persians captured the fortress city of Dara in 573, a devastating blow. A temporary truce was bought with gold, but fighting soon resumed.

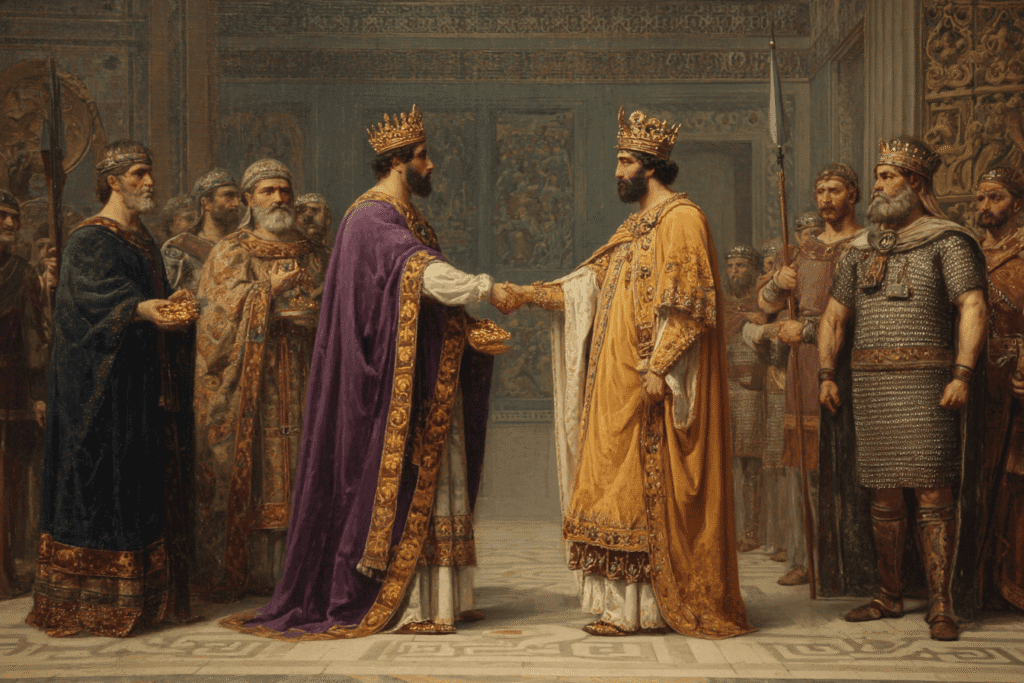

Byzantine fortunes revived under the general Maurice, who took command in 577. He repelled Persian advances and even invaded Persian territory, crossing the Euphrates and threatening Ctesiphon, the Persian capital. The war’s climax came amidst Persian internal strife: King Hormizd IV was assassinated in 590, and his son Khosrow II was forced to flee to Byzantine territory.

In a dramatic reversal, Emperor Maurice allied with the exiled Khosrow II, providing him with troops to reclaim the Persian throne. The combined Roman-Persian force defeated the usurper Bahram Chobin at the Battle of Blarathon in 591, restoring Khosrow II and securing a favorable peace for Byzantium. The Byzantines gained control over much of Armenia and the Caucasus, reaching the zenith of their influence in the region.

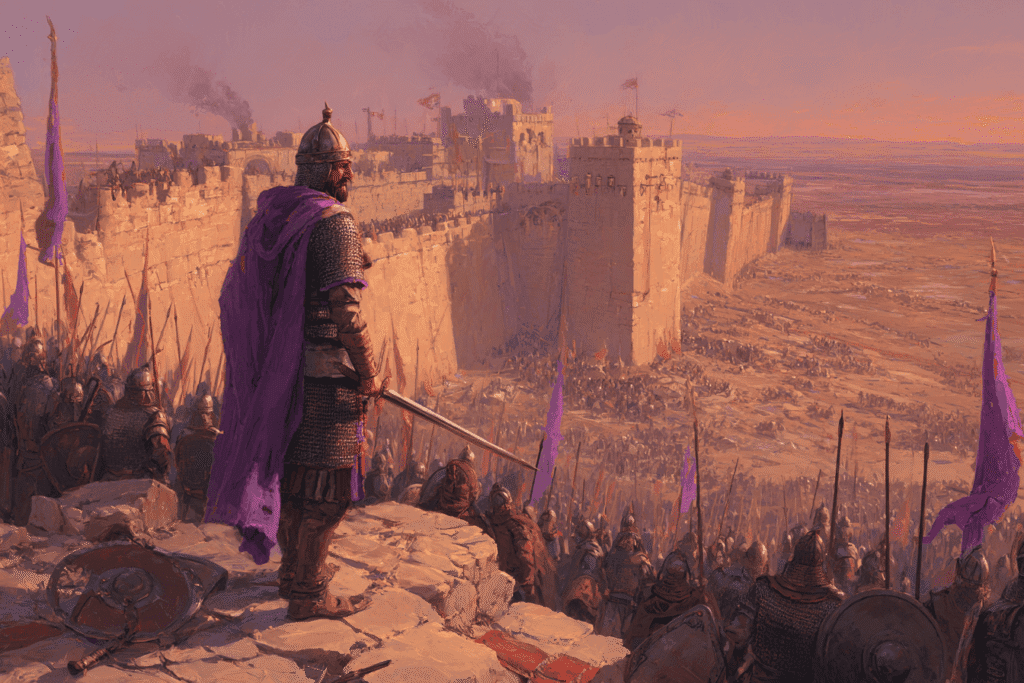

The Last Great War of Antiquity (602–628)

Persian Ascendancy

The initial years of the war saw a string of spectacular Persian successes. Under generals like Shahrbaraz and Shahin, the Sasanian armies swept through the Levant, capturing Damascus, Jerusalem (615), and Alexandria (619). By 615, Persian forces stood at Chalcedon, directly across the Bosphorus from Constantinople itself. The Byzantine Empire was cut in half, its richest provinces lost, and its morale shattered.

Emperor Heraclius, who had come to the throne in 610, faced a crisis so severe that he contemplated abandoning Constantinople for Carthage, or even surrendering to the Persians and becoming their vassal. The empire’s finances were in ruins; treasures from the church and palace were melted down to fund the war effort.

Heraclius Strikes Back

In 622, Heraclius launched a bold counteroffensive. He reorganized his battered army, drilled them in new tactics, and infused them with a sense of holy war. Marching east through Anatolia, he sought to outflank the Persians in Armenia. At the Battle of Ophlimus, Heraclius used deception to lure a Persian detachment from their defensive positions, then routed them with his elite troops – a victory that, while not decisive, restored Byzantine morale and set the stage for greater successes.

Heraclius’s campaigns became legendary for their daring. He marched deep into Persian territory, striking at the heartland and even destroying the sacred Zoroastrian fire temple at Takht-i-Suleiman. In a series of brilliant maneuvers, he repeatedly defeated Persian armies, exploiting rivalries among their commanders and using feigned retreats to lure them into traps.

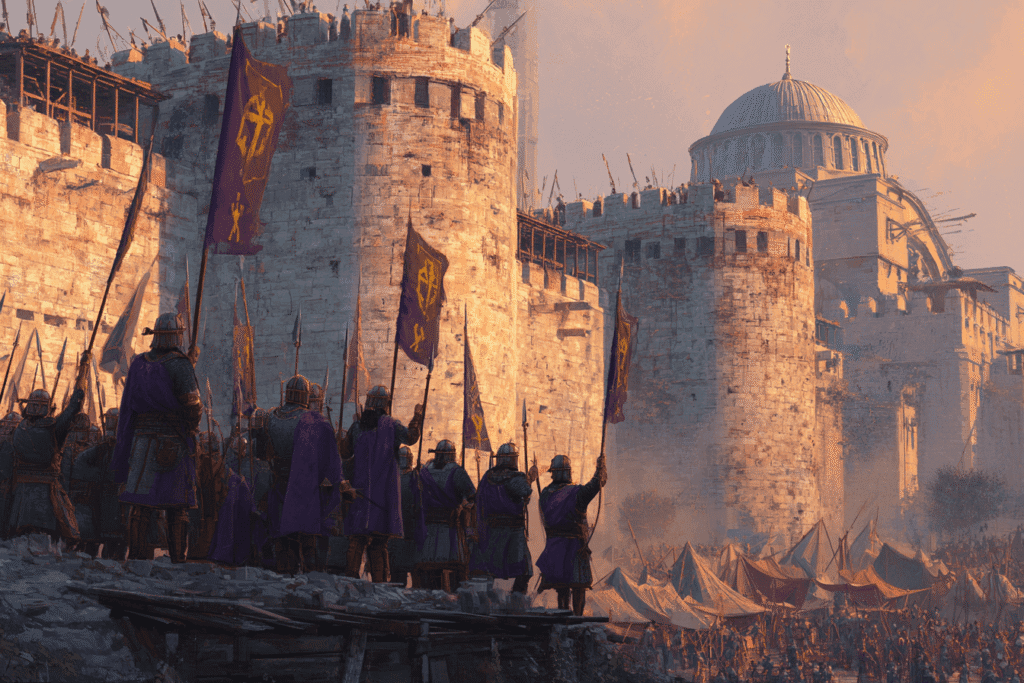

The Siege of Constantinople and the Turning Tide

In 626, the Persians, allied with the Avars and Slavs, launched a massive assault on Constantinople. The city, defended by Heraclius’s trusted lieutenants and the formidable Theodosian Walls, withstood the siege. The failure to take the Byzantine capital marked a turning point. Heraclius, now allied with the Turkic Khazars, pressed his advantage, invading the Persian heartland.

The Battle of Nineveh and the Collapse of Persia

In December 627, Heraclius achieved his crowning victory at the Battle of Nineveh. Outnumbered and deep in enemy territory, he feigned retreat, then turned on the pursuing Persian army in a dense fog. After eight hours of brutal combat, the Persians broke. Heraclius is said to have personally slain the Persian commander Rhahzadh in single combat.

The defeat at Nineveh shattered Persian resistance. Khosrow II was overthrown and executed in a palace coup. The new Persian rulers, desperate to end the war, agreed to peace. All occupied territories were returned, and the war ended with a restoration of the pre-war borders – a status quo ante bellum.

The Aftermath: Exhaustion and Catastrophe

The war of 602–628, the longest and most destructive of the Byzantine-Persian conflicts, left both empires utterly exhausted. Cities and provinces had been devastated by years of occupation, pillage, and heavy taxation. The Persian Empire, wracked by civil war and economic decline, was fatally weakened. The Byzantine Empire, though victorious, was financially ruined and militarily overstretched, with the Balkans lost to Slavic invaders and Anatolia ravaged.

As historian James Howard-Johnston observed, Heraclius’s victories “saved the main bastion of Christianity in the Near East and gravely weakened its old Zoroastrian rival,” but both empires were now shadows of their former selves.

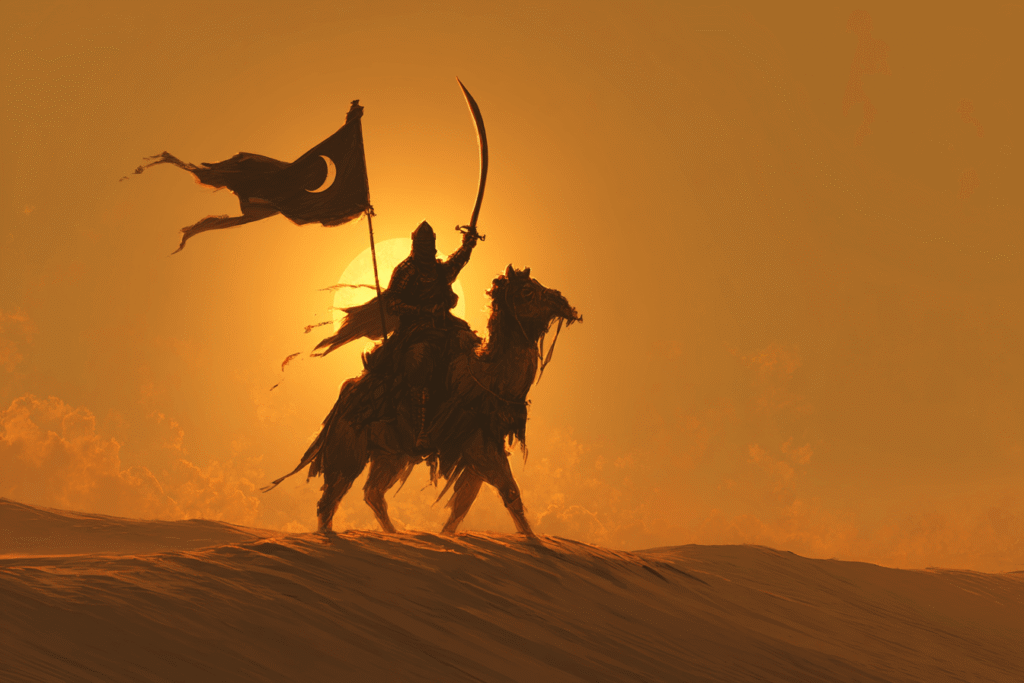

The Unexpected Consequence: The Rise of Islam

Neither empire had time to recover. Within a decade, a new and unexpected force erupted from the Arabian Peninsula: the armies of Islam. Spreading their new religion through conquest, the Rashidun Caliphate swiftly conquered the Levant, Mesopotamia, Persia, Egypt, and North Africa. The Sasanian Empire collapsed entirely, while the Byzantines lost their richest provinces and were reduced to a regional power, locked in a new struggle with the Islamic world.

Conclusion: The End of Antiquity

The Byzantine-Persian Wars were more than a series of military campaigns; they were the final act in the ancient struggle between East and West, pagan and Christian, Rome and Persia. The war of 602-628, known as the “Last Great War of Antiquity,” marked the end of an era. In its wake, the ancient world gave way to the medieval, and the map of the Middle East was redrawn forever.