In the early fifth century, the Roman Empire, once the unchallenged master of the Mediterranean and much of Europe, began to unravel at its fringes. Nowhere was this more evident than in Britain, the remote island province that had been under Roman control for nearly four centuries.

A Distant Outpost

Britain entered the Roman world in 43 CE, when Emperor Claudius launched a full-scale invasion. Over the next decades, Roman armies subdued local tribes, built towns, roads, and forts, and imposed Roman law and culture. By the second century, Britain was a prosperous province, with bustling cities like Londinium (London), Eboracum (York), and Verulamium (St. Albans), and a network of villas and farms in the countryside. Roman Britain was defended by legions stationed along Hadrian’s Wall in the north, and the province was integrated into the empire’s trade and administrative systems.

Life Under Roman Rule

Romanization brought new technologies, architecture, and customs. The local elite adopted Roman ways, and Latin became the language of administration. Towns flourished, coins circulated, and the island was connected to the wider Roman world. Yet, beneath this veneer of civilization, tensions simmered. Many of the native Britons never fully assimilated, and the province remained vulnerable to attacks from beyond its borders.

The Gathering Storm

By the late fourth century, the Roman Empire was beset by crises. Civil wars, economic decline, and relentless pressure from barbarian tribes strained the empire’s resources. Britain, lying at the empire’s northwestern edge, felt these pressures acutely. The province was increasingly isolated, as the empire’s attention shifted to more urgent threats in Gaul, Italy, and the Balkans.

The Barbarian Conspiracy

A crucial moment came in 367 CE, during the so-called “Barbarian Conspiracy.” A series of devastating raids by the Picts from the north, the Scotti from Ireland, and the Saxons from the continent overwhelmed Roman defenses. The attackers exploited a period of internal chaos, including mutinies along Hadrian’s Wall and a breakdown of command. The Roman response was sluggish, and it took years to restore order. This crisis exposed the fragility of Roman control in Britain and foreshadowed the province’s vulnerability.

Recent research suggests that climate may have played a role in these troubles. Tree-ring data indicates a series of severe droughts in the 360s, which would have crippled agriculture and contributed to food shortages. Such environmental stress could have exacerbated social unrest and weakened the ability of Roman authorities to maintain order.

The Final Years of Roman Britain: Usurpers and Wthdrawals

The late fourth and early fifth centuries were marked by a series of military usurpations. In 383, Magnus Maximus, a general stationed in Britain, declared himself emperor and withdrew many troops to support his claim on the continent. This set a precedent: when later usurpers needed troops, Britain was a convenient recruiting ground. Each time, the province was left more exposed.

The decisive blow came in 406-407, when Constantine III, another usurper, was proclaimed emperor by the army in Britain. He led the remaining field army across the Channel to Gaul, hoping to seize the imperial throne. These troops never returned. With the military backbone gone, Britain was left to fend for itself against increasing raids and internal disorder.

In 410, the emperor Honorius, besieged in Italy by Visigoths, reportedly sent a letter to the cities of Britain, instructing them to “look to their own defenses.” This message, known as the Honorian Rescript, is often cited as the formal end of Roman rule in Britain. In reality, it was the culmination of a long process of decline, as imperial authority faded and local leaders took matters into their own hands.

The End of Central Authority

With the departure of the legions and the collapse of central government, Roman Britain fragmented. Urban life declined rapidly: towns were abandoned or shrank to shadows of their former selves. The sophisticated administrative apparatus that had governed the province disappeared, replaced by local warlords and councils.

For the Romano-British elite, the end of Roman rule was a disaster. They lost the protection of the empire, the prestige of Roman citizenship, and the economic benefits of imperial trade. Some tried to maintain Roman ways, but without support from the continent, their position was untenable. Many retreated to fortified villas or fled to the western uplands, where Roman influence lingered longest.

The Rise of Local Powers

In the absence of Roman authority, power devolved to local chieftains and councils. Some of these leaders were former Roman officials; others were native Britons who seized the opportunity to assert themselves. The political landscape became fragmented, with competing kingdoms vying for dominance. This period, known as Sub-Roman Britain, was marked by instability and frequent conflict.

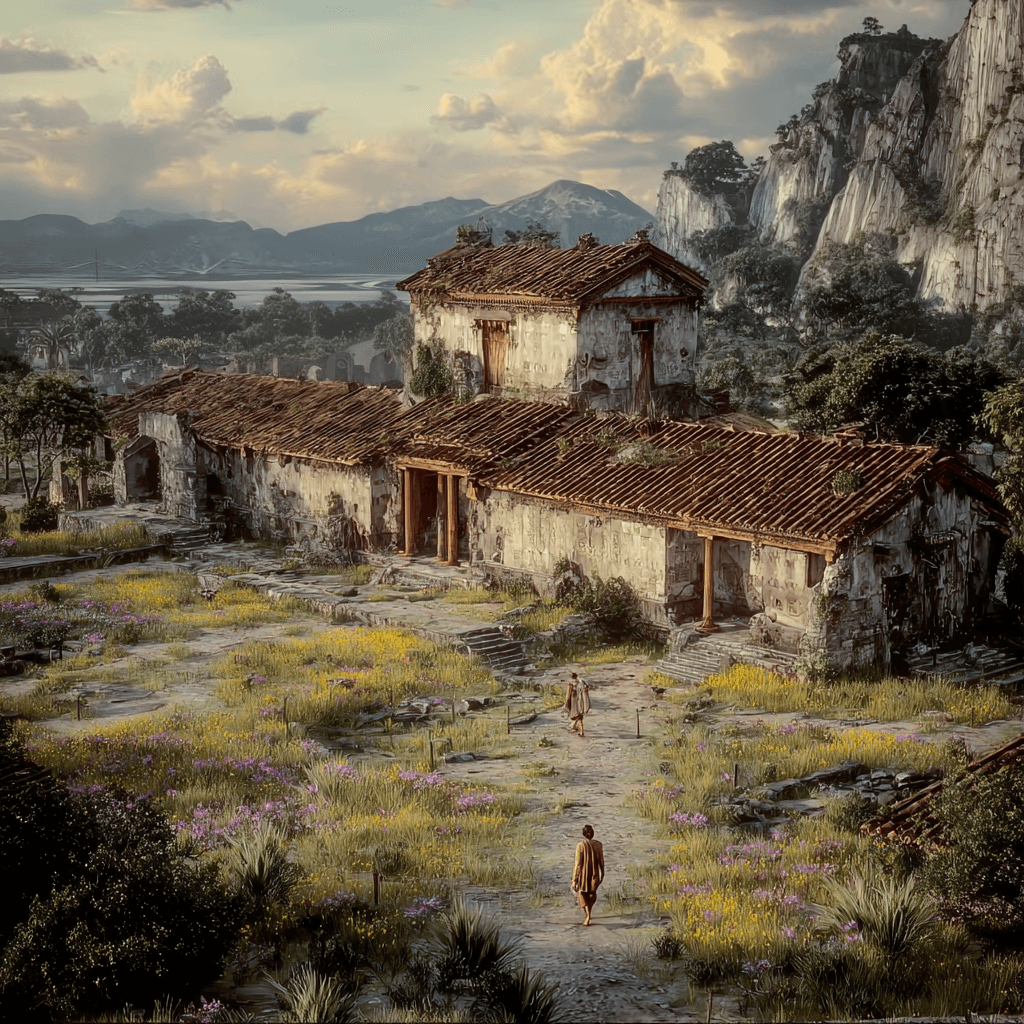

Archaeological evidence shows a dramatic decline in urban activity. Public buildings fell into disrepair, coinage ceased, and imported goods vanished. The complex economy of Roman Britain gave way to subsistence farming and barter. The once-bustling towns became ghostly reminders of a lost world.

The Coming of the Saxons

As Roman protection vanished, Britain became a target for new waves of invaders. The Saxons, Angles, and Jutes – Germanic peoples from across the North Sea – began to settle in increasing numbers. Some were initially hired as mercenaries to defend against other raiders, but soon they became conquerors in their own right.

Over the course of the fifth and sixth centuries, the Anglo-Saxons gradually displaced the Romano-British from the lowlands. The old Roman towns and villas were abandoned or destroyed, and the Latin language faded from everyday use. The material culture of Roman Britain – its pottery, coins, and architecture – disappeared, replaced by simpler, Germanic styles.

Despite the collapse, Roman influence did not vanish overnight. In some areas, especially in the west and north, Roman customs, Christianity, and elements of Latin survived for generations. The memory of Rome lingered in legend and literature, shaping the identity of later British kingdoms.

Causes of the Withdrawal

Political Instability

The Roman Empire in the late fourth and early fifth centuries was plagued by civil wars, usurpations, and a succession of weak emperors. The central government’s ability to project power to distant provinces like Britain was fatally compromised. Usurpers repeatedly drained Britain of troops, leaving it defenseless.

The empire’s frontiers were under constant attack from barbarian groups: Goths, Vandals, Huns, and others. The Rhine frontier collapsed in 406, unleashing a wave of invasions into Gaul. Defending Italy and Gaul took priority over distant Britain, which was left to fend for itself.

Economic Decline

Maintaining the army and infrastructure in Britain was expensive. As the empire’s finances deteriorated, resources were redirected to more critical regions. The collapse of trade networks further undermined the province’s economy, making it increasingly difficult to sustain Roman life.

Periods of drought and crop failure in the late fourth century weakened the province’s ability to support its population and military. Environmental stress contributed to social unrest and made Britain more vulnerable to external threats.

The Human Experience: Voices from the Edge

For the Romanized elite, the end of empire was a personal catastrophe. They lost their status, wealth, and security. Some tried to maintain Roman traditions, clinging to Latin, Christianity, and the trappings of Roman culture. Others adapted, forging alliances with local leaders or even with incoming Saxons.

For most Britons, the end of Roman rule meant the collapse of familiar institutions. Taxes and conscription ceased, but so did the protection of the legions. Many retreated to rural life, relying on kinship and local networks for survival. The transition was traumatic, but it also opened new opportunities for those willing to seize them.

For the Saxons and other newcomers, Britain was a land of opportunity. They settled, farmed, and eventually established their own kingdoms. The fusion of Romano-British and Germanic cultures laid the foundations for medieval England.

The Legacy of Roman Withdrawal

The centuries following the Roman withdrawal have often been called the “Dark Ages,” a term that suggests chaos and decline. While there was certainly disruption, recent scholarship emphasizes the resilience and adaptability of the population. Local leaders filled the power vacuum, new forms of art and architecture emerged, and Christianity survived and even flourished in some areas.

Roman roads, walls, and ruins remained visible reminders of the lost empire. The idea of Rome as a model of civilization persisted, influencing later kings and chroniclers. The legend of King Arthur, for example, reflects the longing for a lost golden age of order and justice.

Out of the chaos of post-Roman Britain emerged the early medieval kingdoms of England, Wales, and Scotland. These new polities drew on both Roman and native traditions, blending them in creative ways. The legacy of Rome was thus both a memory and a foundation for the future.

Conclusion

The withdrawal of Roman authority from Britain was a watershed moment in the island’s history. It marked the end of centuries of imperial rule and the beginning of a new era of fragmentation, conflict, and transformation. The process was shaped by a complex interplay of political, military, economic, and environmental factors, and its impact was felt for generations. Yet, out of the ashes of Roman Britain arose the seeds of the medieval world – a world that would, in time, look back on Rome with both nostalgia and inspiration.

The story of the Roman withdrawal from Britain is not just a tale of decline and fall, but also one of survival, adaptation, and renewal. It reminds us that the end of one world is often the beginning of another, and that the legacies of empire can endure long after the last legion has marched away.