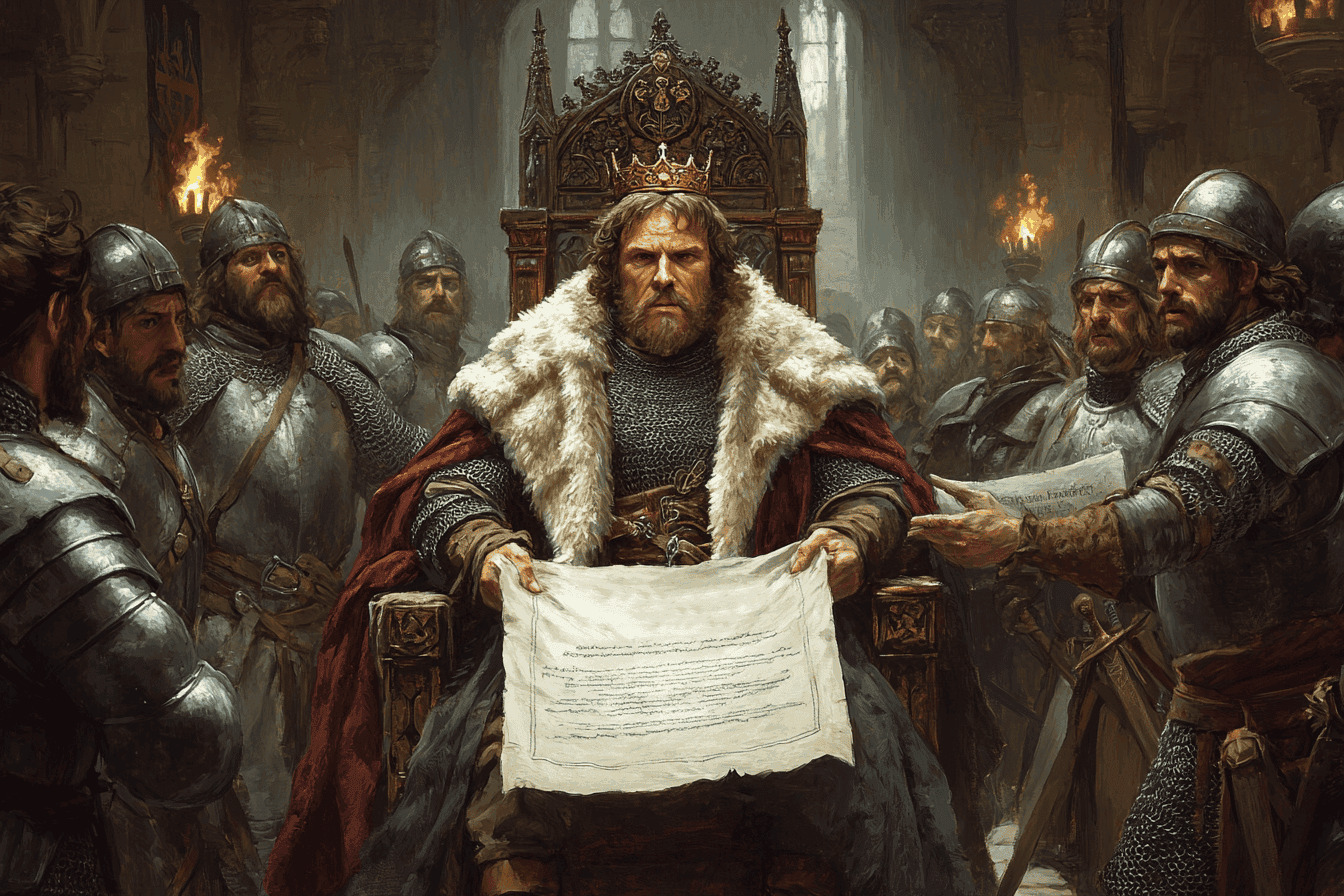

The year 1215 marked a pivotal moment in English history when King John, under immense pressure from his barons, agreed to the terms of the Magna Carta. This “Great Charter,” sealed on June 15 at Runnymede, was not only a product of its time but also a document that would resonate through centuries as a symbol of the rule of law and the limitation of arbitrary power. However, its immediate significance lay in its attempt to resolve a bitter conflict between the monarchy and the feudal elite, a conflict born of King John’s controversial reign.

The Context: King John’s Troubled Rule

King John ascended to the throne in 1199, inheriting a vast Angevin Empire that included England and large swathes of France. However, his reign was plagued by military failures, heavy taxation, and political mismanagement. In 1204, John suffered a catastrophic loss when Normandy and Anjou were seized by King Philip II of France. Determined to reclaim these territories, John embarked on costly military campaigns that drained the royal treasury and alienated his barons. To fund his ambitions, he raised taxes to unprecedented levels and employed increasingly oppressive methods of collection.

John’s personal traits further exacerbated his unpopularity. Chroniclers described him as ruthless, vindictive, and untrustworthy. His disputes with the Church, including his excommunication by Pope Innocent III in 1209 over the appointment of Stephen Langton as Archbishop of Canterbury, deepened his isolation. Though reconciliation with the Pope was achieved in 1213, John’s reputation had already been severely damaged.

War with France

The roots of the war lay in decades of rivalry between the Capetian kings of France and their Angevin (English) and imperial adversaries. By 1214, King Philip II Augustus had consolidated much of his power through territorial expansion, notably reclaiming Normandy from King John in 1204. This success alarmed neighboring rulers, particularly John and Otto IV, who sought to curb Philip’s growing influence.

In early 1214, an anti-French coalition was formed. It included:

- Otto IV, Holy Roman Emperor, who sought to reassert imperial dominance.

- King John of England, desperate to recover lost Angevin territories in France.

- Count Ferrand of Flanders and Count Renaud of Boulogne, who resented Philip’s encroachments on their lands.

- Several other nobles from across Europe, including Duke Henry I of Brabant and Count William I of Holland.

The coalition devised a two-pronged strategy: while John launched an invasion in western France, Otto would lead a larger force into northern France.

Battle of Roche-au-Moine

However, John’s advance was halted at the castle of La Roche-aux-Moines, located just south of Angers. This newly constructed fortress, likely built under the orders of Philip II of France, proved to be a formidable obstacle. John laid siege to the castle, but its garrison, commanded by the capable Guillaume des Roches, Seneschal of Anjou, held firm.

The siege took an unexpected turn when news arrived of an approaching French relief force. Prince Louis, heir to the French throne, had assembled a formidable army of 800 knights at Chinon. Accompanying the prince were several prominent French nobles, including Amauri I de Craon and Henri Clement, the Marshal of France.

As the French army neared, John faced a critical decision. His position was precarious, and the loyalty of his allies was wavering. The powerful Poitevin lords, including the houses of Thouars and Lusignan, had been crucial to John’s initial success. However, upon hearing of the size of the French force, these allies began to desert the English king.

Realizing the gravity of his situation, John made the difficult choice to abandon the siege. He ordered the destruction of his siege engines and prepared for a hasty retreat. This decision likely saved his army from a potentially disastrous defeat, but it also marked the end of his offensive in Anjou.

The Battle of Roche-au-Moine itself was less a pitched battle and more a strategic victory for the French. Prince Louis and Guillaume des Roches effectively outmaneuvered John, forcing him to withdraw without engaging in direct combat. The English retreat was so swift that John fell back all the way to La Rochelle on the Atlantic coast.

This engagement had significant repercussions for John, it represented a major setback in his attempts to reclaim his lost continental possessions. The aftermath of Roche-au-Moine saw a shift in the balance of power in western France. Many of the lords who had previously supported John now turned to Philip II, recognizing the ascendancy of French royal power. The Angevin territories, long contested between England and France, fell firmly under Capetian control.

The Battle of Bouvines

With King John’s English forces in disarray, the responsibility for defeating the French was focussed on the coalition led by Otto IV, Holy Roman Emperor, whose armies had moved into France.

The two armies met near Bouvines on July 27, 1214. The French forces, numbering around 7,000–9,000 men, were outnumbered by Otto’s coalition army, estimated at around 9,000–12,000 troops. Despite this numerical disadvantage, Philip’s disciplined army and strategic leadership proved decisive.

Both armies adopted similar formations:

- Cavalry positioned on the wings.

- Infantry concentrated in the center.

Philip himself commanded a reserve cavalry unit and positioned his royal standard—the Oriflamme—at the rear.

The battle began with a cavalry clash on the French right wing. French knights under Eudes III, Duke of Burgundy, routed their Flemish counterparts led by Count Ferrand. Ferrand was captured early in the fight.

In the center, Otto’s imperial infantry initially pushed back French urban militias and nearly reached Philip himself. During this critical moment, Philip was unhorsed but quickly remounted with assistance from his men. A counterattack by French knights shattered Otto’s infantry formation and forced him to retreat.

On the French left wing, Robert de Dreux faced William Longespée (Earl of Salisbury). Longespée fought valiantly but was unhorsed and captured by Philip’s forces. The allied right wing collapsed soon after.

The final act came as Renaud of Boulogne formed a defensive ring with several hundred Brabançon pikemen. Despite their bravery and repeated sorties by Renaud himself, they were eventually overwhelmed by French knights led by Thomas de St. Valery. Renaud was captured alive.

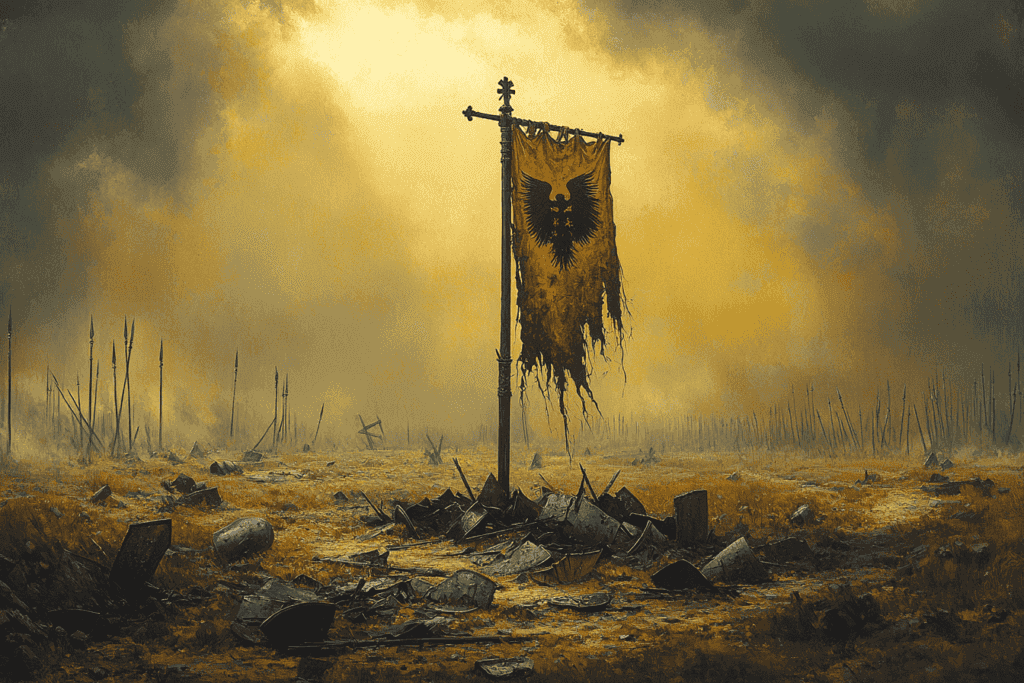

By nightfall, the coalition army was decisively defeated. Otto fled the battlefield but lost his imperial eagle standard – a symbolic humiliation.

Aftermath

Philip’s victory at Bouvines cemented his position as one of Europe’s most powerful monarchs: it ended immediate threats to his territorial gains in Normandy and other regions, it boosted royal authority within France as the victory became a cornerstone for French national identity; chroniclers hailed it as divine favor for Philip’s rule.

Philip returned to Paris in triumph with captured nobles paraded through the streets – a powerful display of his dominance.

For Otto the defeat marked the end of his reign as Holy Roman Emperor: he lost credibility among German princes who shifted their support to Frederick II, and Otto retreated to Harzburg Castle and lived in obscurity until his death in 1218.

The defeat at Bouvines was catastrophic for King John as it dashed any hopes of regaining Normandy and left him politically vulnerable. The barons saw an opportunity to challenge his authority and began organizing their resistance.

The Road to Runnymede

The immediate catalyst for rebellion came in early 1215 when the barons formally presented their grievances to John. These demands were rooted in earlier traditions, such as Henry I’s Charter of Liberties (1100), which sought to limit royal abuses and protect noble privileges. Negotiations between John and the barons began in earnest but quickly stalled as neither side trusted the other.

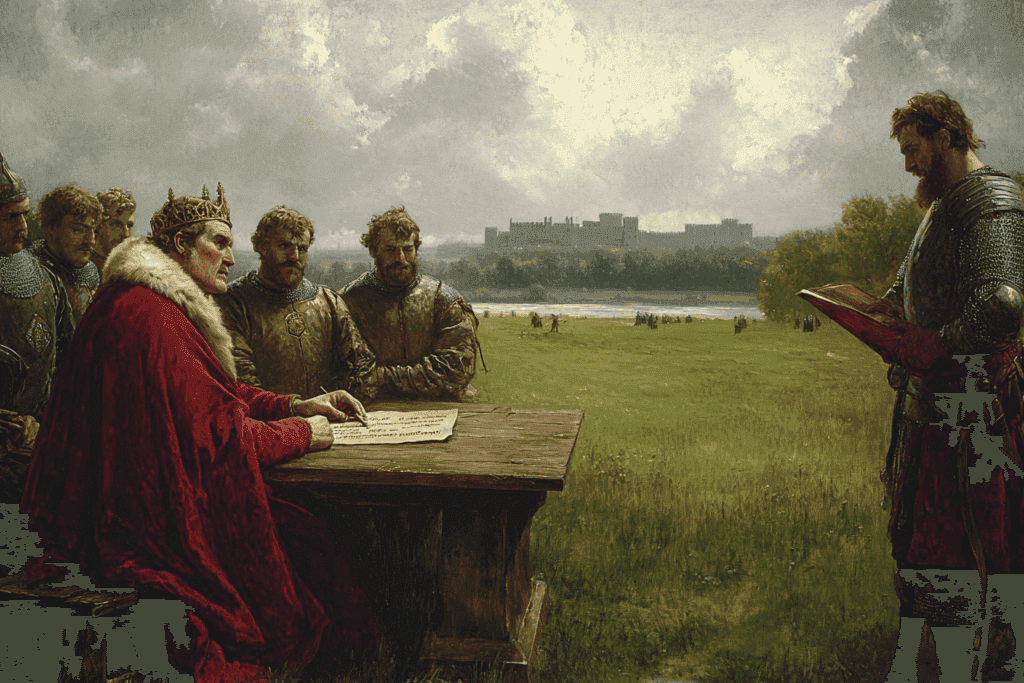

By May 1215, tensions escalated into open conflict when rebel barons captured London. Their occupation of the capital forced John into a corner; he could not afford a prolonged civil war. Under pressure, he agreed to meet the barons at Runnymede, a neutral site near Windsor Castle.

The Magna Carta: Content and Significance

On June 15, 1215, King John affixed his seal to what would later be known as the Magna Carta. Drafted as a peace treaty between the king and his rebellious barons, it addressed specific grievances while laying down broader principles for governance. Its key provision were:

- Protection of Church Rights: The Magna Carta guaranteed the freedom of the Church from royal interference.

- Legal Reforms: It promised protection from illegal imprisonment (a precursor to habeas corpus) and access to swift justice.

- Taxation with Consent: The charter restricted the Crown’s ability to impose taxes without consulting a council of barons.

- Feudal Rights: It regulated feudal payments owed to the king and provided safeguards against arbitrary seizures of land.

- Clause 61 (Security Clause): This controversial clause established a council of 25 barons tasked with ensuring John’s compliance with the charter. If he failed to adhere to its terms, they were empowered to seize royal property until grievances were addressed.

While these provisions primarily served the interests of the nobility, some clauses extended protections to free men more broadly. However, it is important to note that serfs – who constituted the majority of England’s population – were excluded from these rights.

Immediate Aftermath

Despite its groundbreaking nature, the Magna Carta was never intended as a permanent settlement. Both sides viewed it as a temporary truce rather than a lasting solution. Within weeks, cracks began to appear in the agreement.

King John sought assistance from Pope Innocent III, arguing that he had been coerced into signing the charter. In August 1215, Innocent annulled the Magna Carta, declaring it “illegal and unjust” because it undermined royal authority and papal rights. This papal intervention emboldened John, who repudiated the charter entirely.

Meanwhile, tensions between royalist forces and rebel barons reignited into open warfare by late 1215. The First Barons’ War saw both sides vying for control of England. The rebels invited Prince Louis of France (later Louis VIII) to claim the English throne, further complicating matters.

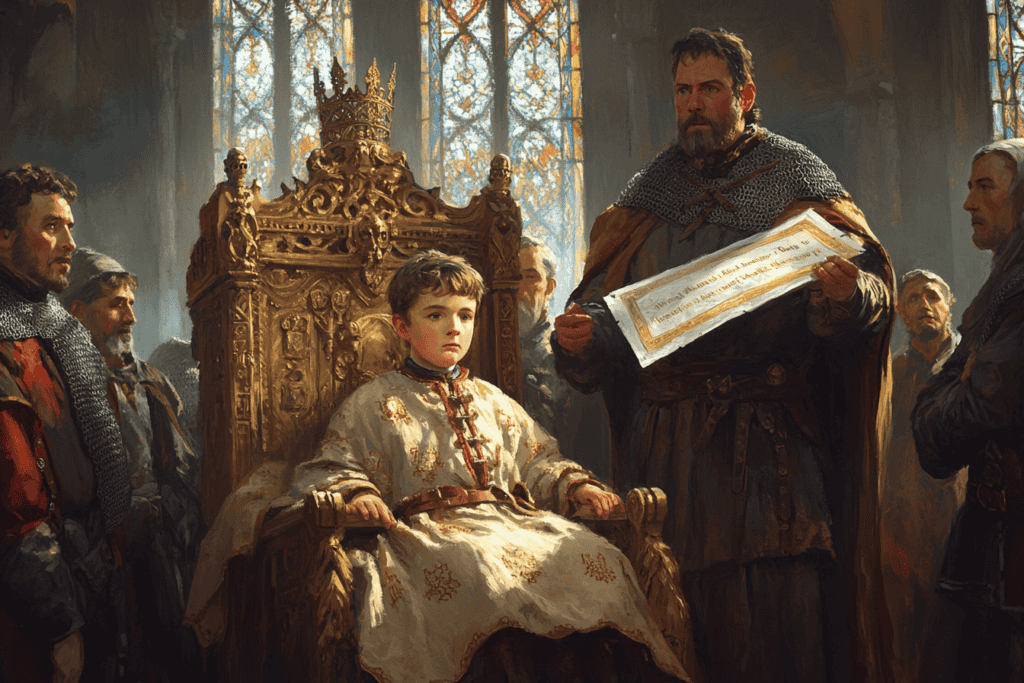

John’s death in October 1216 brought an unexpected turn of events. His nine-year-old son, Henry III, inherited the throne under the regency of William Marshal. To stabilize the kingdom, Marshal reissued a revised version of the Magna Carta in 1216 and again in 1217—this time without Clause 61—to placate both sides.

Legacy

Although its initial impact was limited—being annulled within months—the Magna Carta’s legacy grew over time. Subsequent kings reissued modified versions during periods of political unrest or negotiation with their subjects. By embedding principles such as accountability and consent into English governance, it laid the groundwork for constitutional developments in later centuries.

The Magna Carta’s influence on modern governance:

- The Magna Carta established that no one—not even the king—is above the law.

- Its emphasis on consultation foreshadowed the development of parliamentary systems.

- The Magna Carta inspired constitutional documents worldwide, including the United States Constitution and Bill of Rights.

Today, it is often regarded as a cornerstone of liberty and justice despite its original focus on feudal concerns. Its enduring appeal lies in its assertion that power must be exercised within legal limits – a principle that continues to resonate globally.