Frederick I Barbarossa, the Holy Roman Emperor, took the cross on March 27, 1188, finally committing to join the Third Crusade and reclaim the Holy Land. This momentous decision came after months of appeals and deliberation, as the Crusader States had been pleading for his assistance since 1187. The fall of Jerusalem to Saladin in October 1187 had sent shockwaves through Christendom, prompting Pope Gregory VIII and his successor Clement III to call for a new crusade.

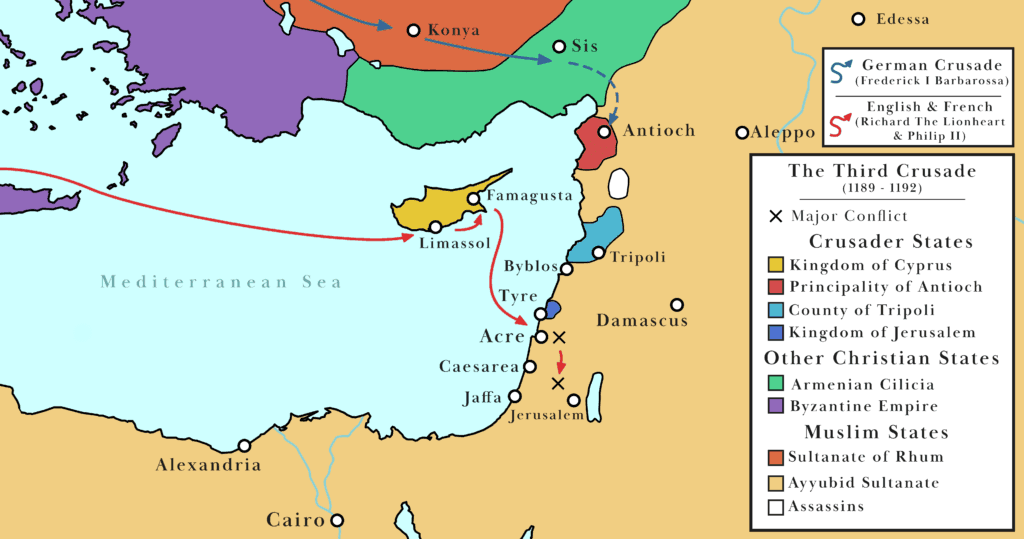

Barbarossa’s participation in the Third Crusade was highly anticipated, given his reputation as a powerful and experienced ruler. At nearly 70 years old, he had already participated in the Second Crusade decades earlier. Despite his advanced age, Barbarossa assembled the largest crusader army seen to date, setting out in May 1189 with a force that crossed through Hungary into Byzantine territory.

The journey east was fraught with challenges from the outset. The Byzantine Emperor Isaac II Angelus, bound by a secret treaty with Saladin, attempted to impede Frederick’s progress through Greece to the Holy Lands. This understandably led to tensions between the crusaders and Byzantines.

Adrianople

As Frederick approached Adrianople, a major Byzantine town 150 miles from Constantinople, he decided to act. Recognizing the city’s importance as a potential base of operations, his army swiftly surrounded the city. The German emperor’s reputation preceded him, and the mere presence of his forces struck fear into the hearts of the Byzantine defenders.

Frederick’s soldiers established a tight perimeter around the Adrianople. The German artillery, more mobile than that of his contemporaries, was strategically positioned to bombard the city’s defenses. The constant barrage weakened Adrianople’s walls and demoralized its defenders. Meanwhile, Frederick’s infantry, maintained a relentless pressure on the city’s garrison.

The German emperor’s strategic wisdom was evident when he sent word to his son Henry in Germany, requesting a fleet to be sent to Constantinople, and even appealed to the Pope for permission to launch a Crusade against the Byzantines. These actions, while not immediately impacting the siege, served to increase pressure on the Byzantine Emperor Isaac II Angelos and demonstrated the German emperor’s resolve. The constant pressure from the German forces, combined with the threat of a potential attack on Constantinople itself, wore down the Byzantine resistance.

Frederick’s capture of Adrianople was not just a military victory but also a masterclass in strategic thinking. He understood the importance of the city not only for its immediate tactical value but also for its potential as a bargaining chip in negotiations with the Byzantine Emperor. This foresight would prove crucial in the aftermath of the siege.

The fall of Adrianople to Frederick’s forces was a turning point in his campaign. The speed and efficiency with which he captured the city demonstrated the German army’s capabilities and sent shockwaves through the Byzantine Empire. Emperor Isaac II Angelos, realizing the gravity of the situation, was forced to sue for peace.

In the negotiations that followed, Frederick’s possession of Adrianople gave him a strong bargaining position. He used this advantage to secure guarantees for his army’s safe passage across Byzantine territory. The treaty that resulted from these negotiations allowed Frederick to continue his crusade while avoiding further conflict with the Byzantines. Once Isaac agreed to transport the German Crusaders across the Hellespont into Asia Frederick returned control of the city to the Byzantines.

Unexpected conflict with the Turks

Once past Constantinople, the German crusader army encountered unexpected resistance upon entering Turkish territory, despite prior arrangements for safe passage. The Seljuk Turks continuously harassed the Crusader forces, laying ambushes and using hit-and-run tactics. On April 30, the Crusaders successfully repelled a Turkish attack on their camp, killing 500 enemy soldiers. They followed this with another victory on May 2, slaying 300 Turks.

On May 3, the Crusaders faced a Turkish ambush, resulting in the death of a knight named Werner and injuries to Frederick VI, Duke of Swabia, along with nine other knights. In retaliation, the Crusaders killed sixty of the ambushers and then committed atrocities against Turkish women and children in a nearby lowland area.

The Crusaders reached Philomelion on May 7, where they faced a significant Turkish assault of 10,000 troops that evening. Led by Frederick VI and Berthold, Duke of Merania, a Crusader force of 2,000 men rode out of their camp and successfully routed the Turkish attackers, killing almost 5,000.

As the Crusaders continued their march, their ranks increasingly thinned by hunger, they engaged in several more skirmishes with Turkish forces. Between May 9-11, they killed over 300 Turkish soldiers. On 14 May, the Crusaders found and defeated the main Seljuk army, putting it to rout. Seljuk records attribute the Crusader victory to a devastating charge of 7,000 heavy cavalry.

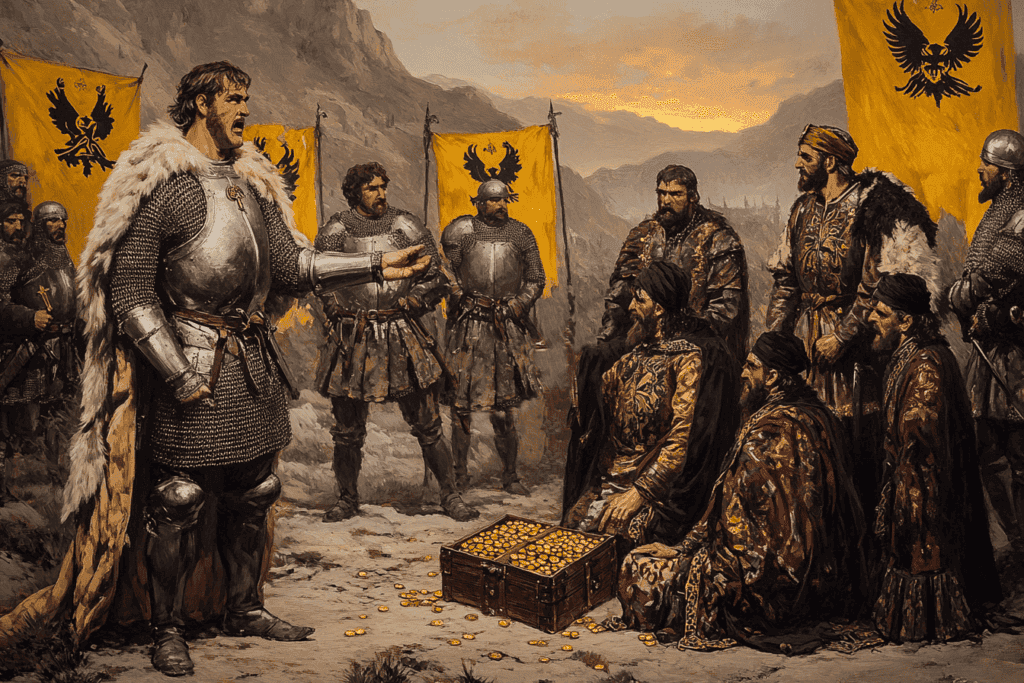

Two days later, the Seljuk Turks offered to let Barbarossa’s army pass through their territory for the price of 300 pounds of gold and the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia. The German emperor refused, supposedly saying: “Rather than making a royal highway with gold and silver, with the help of our Lord Jesus Christ, whose knights we are, the road will have to be opened with iron”. On May 18 his army reached the Seljuk capital of Iconium, setting the stage for a major battle on May 18.

The Battle of Iconium

The Crusaders established their camp in the sultan’s gardens outside the city, where they found ample water supplies. Qutb al-Din, the Seljuk Turk leader, had regrouped and strengthened his forces after the initial defeat, preparing to defend his capital.

Barbarossa split his army into two groups: one led by his son, Duke Frederick of Swabia, to assault the city, and the other commanded by himself to face the Turkish field army. The city fell quickly, with Duke Frederick’s forces easily breaching the walls and encountering minimal resistance from the garrison, which swiftly surrendered. The Germans then proceeded to massacre the city’s inhabitants.

The battle against the Turkish field army proved more challenging, requiring Emperor Barbarossa’s presence to overcome the larger Turkish force. Despite the intense fighting, the Germans managed to decisively defeat the Turks, who were routed once again with a further 3,000 killed. The Crusaders did not pursue the fleeing enemy, partly due to food shortages they had experienced in the previous two weeks.

Following their victory, the Crusaders acquired substantial booty from the city, valued at 100,000 marks. They spent five days resting in the city and camped in the sultan’s park. During this time, they purchased over 6,000 horses and mules, and replenished their supplies of bread, meat, butter, and cheese. On May 26, they resumed their march, taking 20 high-ranking Turkish nobles as hostages for their protection.

The success of the Imperial army greatly concerned Saladin, who was forced to weaken his forces at the Siege of Acre and dispatch troops northward to impede the Germans’ advance. The German crusaders seemed unstoppable, their massive numbers and Frederick’s tactical acumen overcoming all obstacles. For Saladin and his Muslim forces, the impending arrival of Barbarossa’s army was a source of great concern.

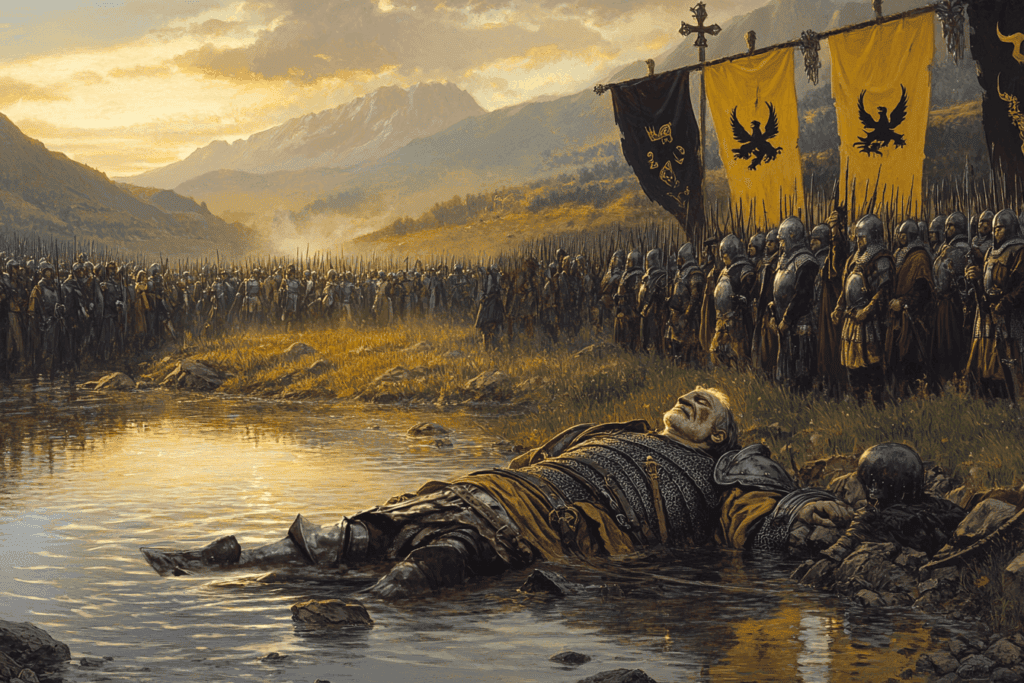

The Tragedy at the Göksu River

However, fate had other plans for the aging emperor. On June 10, 1190, while attempting to cross the Göksu River near Silifke, it is said that Frederick Barbarossa’s horse slipped and weighed down by his heavy armor the emperor drowned. This shocking turn of events dealt a devastating blow to the German crusading effort. The death of their revered leader crushed the morale of the German army, and the majority of the force elected to return home, rather than continue the arduous journey to the Holy Land.

The remnants of Frederick’s Crusader army faced a devastating outbreak of disease near Antioch, further diminishing their already reduced numbers. Only a fraction of the original force, approximately 5,000 soldiers, managed to reach Acre. The German contribution to the Third Crusade, which had seemed so promising, was ultimately minimal due to a tragic accident.

Their primary objective shifted to fulfilling Barbarossa’s wish for burial in Jerusalem. However, attempts to preserve the emperor’s body using vinegar proved unsuccessful. As a result, Barbarossa’s remains were divided and interred in different locations across the Holy Land: his flesh was laid to rest in the Cathedral of Saint Peter in Antioch, his bones found their final resting place in the Cathedral of Tyre and his heart and internal organs were entombed in Saint Paul’s Church in Tarsus.

The Impact on the Crusade

For Saladin and his forces, Barbarossa’s unexpected demise seemed almost miraculous, an act of divine intervention that removed a formidable threat to their control of the Holy Land. The Muslim leaders, who had been bracing for a massive onslaught, now found themselves facing a significantly diminished enemy.

The loss of Barbarossa and the bulk of his forces left the burden of the crusade primarily on the shoulders of the other European monarchs who had taken the cross: King Philip II of France and King Richard I of England. These rulers, who had put aside their own conflicts to join the crusade, now faced an even greater challenge without the support of the Holy Roman Emperor and his substantial army.

The Siege of Acre

Despite the setback of Barbarossa’s death, the Third Crusade pressed on. The focus of the conflict centered on the strategic port city of Acre, which had been under siege by Crusader forces led by Guy of Lusignan since 1189. The arrival of the French and English forces in 1191 reinvigorated the Crusader effort at Acre. King Philip II and King Richard I brought much-needed supplies and fresh troops to the besieging army. Their presence tipped the balance in favor of the Crusaders, and after a prolonged and grueling siege, Acre finally fell to the Christian forces in July 1191.

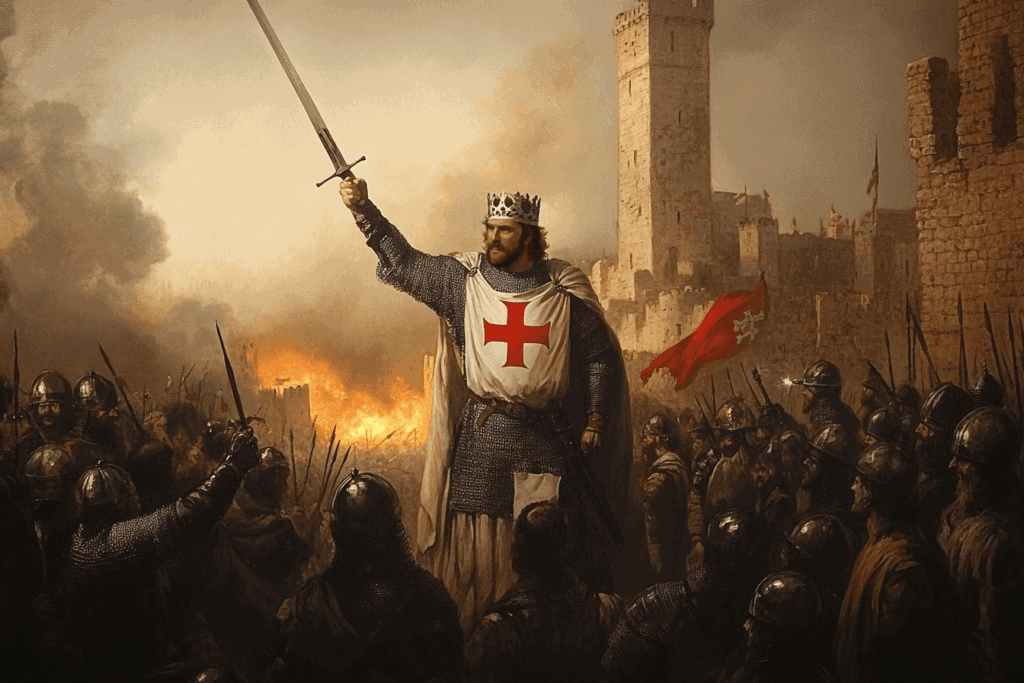

Richard the Lionheart Takes Command

With the capture of Acre, King Richard I, known as the Lionheart, emerged as the de facto leader of the Crusade. His military prowess and bold tactics would come to define the remainder of the campaign.

One of Richard’s most significant victories came at the Battle of Arsuf on September 7, 1191. Here, the English king’s tactical genius shone as he defeated Saladin’s forces in a pitched battle. This victory boosted Crusader morale and demonstrated that Saladin was not invincible.

The March to Jerusalem

As the Crusaders advanced towards Jerusalem, they faced constant harassment from Saladin’s forces. The Muslim leader employed scorched earth tactics, destroying crops and poisoning wells to slow the Crusader advance. Despite these challenges, Richard’s army pressed on, recapturing the port city of Jaffa in the process.

By January 1192, the Crusader army had reached Beit Nuba, just 12 miles from Jerusalem. The holy city, the primary objective of the Crusade, seemed within reach. However, Richard faced a difficult decision. While capturing Jerusalem would be a tremendous symbolic victory, holding the city in the long term would be challenging without control of the surrounding territory.

Negotiations and Conclusion

Recognizing the strategic challenges, Richard entered into negotiations with Saladin. These talks were characterized by mutual respect between the two leaders, both of whom recognized the other’s military skill and chivalric qualities.

The negotiations resulted in the Treaty of Jaffa, signed on September 2, 1192. This agreement allowed Christian pilgrims access to Jerusalem and maintained Crusader control over the coastal cities they had captured. While it fell short of the Crusade’s original goal of reclaiming Jerusalem, it was a pragmatic solution that brought an end to the immediate conflict.

Legacy of the Third Crusade

The Third Crusade, while failing to recapture Jerusalem, was not without significant achievements. The Crusaders had managed to reverse many of Saladin’s conquests, recapturing important coastal cities and securing access to holy sites for Christian pilgrims. These gains helped to stabilize the remaining Crusader states in the Levant, ensuring their survival for several more decades.

For Frederick Barbarossa, the Third Crusade represented both the culmination and the tragic end of a long and illustrious career. His death enroute to the Holy Land robbed the Crusade of one of its most powerful leaders and altered the course of the campaign. Yet, his decision to take the cross and lead such a massive force eastward demonstrated the enduring appeal of the crusading ideal among European monarchs of the late 12th century.