The Fifth Crusade, which took place from 1217 to 1221 CE, stands as a pivotal chapter in the history of the Crusades. This ambitious military campaign, called by Pope Innocent III, aimed to recapture Jerusalem from Muslim control by first weakening the enemy through attacks on Muslim-held cities in North Africa and Egypt. However, what began as a promising endeavor would ultimately end in failure, leaving the Crusaders with little to show for their efforts.

The Call to Arms

In 1215, Pope Innocent III issued a call for the Fifth Crusade. This appeal came in the wake of previous unsuccessful attempts to regain control of Jerusalem, particularly following the failures of the Second, Third, and Fourth Crusades. The loss of Jerusalem to Saladin during the Second Crusade and the inability to recapture it during the Third Crusade had left a bitter taste in the mouths of European Christians. The misguided Fourth Crusade, which had resulted in the sack of Constantinople rather than any meaningful progress in the Holy Land, only added to the urgency of a new campaign.

The Pope’s call resonated across Europe, drawing participants from various regions including France, Hungary, Germany, Portugal, and Georgia. It is estimated that over 30,000 Crusaders answered the call, forming a formidable force ready to embark on this holy mission.

Leadership and Composition

The leadership of the Fifth Crusade was complex and, at times, contentious. Initially, many expected Frederick II Hohenstaufen, King of Germany, to lead the Crusade. However, Frederick was preoccupied with ruling his vast European territories and negotiating his elevation to Holy Roman Emperor. His absence would prove to be a significant factor in the Crusade’s ultimate failure.

In the absence of Frederick II, the Crusaders chose John of Brienne, the titular King of Jerusalem, as their leader. John’s kingdom, based in Acre, did not actually include Jerusalem at the time, adding a layer of irony to his position. The arrival of the papal legate, who controlled the Crusade’s funding, further complicated the leadership structure.

Other notable figures who joined the Crusade included:

- Andrew II of Hungary: Often considered the first leader of the Fifth Crusade, Andrew departed for the Holy Land in July 1217 with a substantial army.

- Leopold VI of Austria: Accompanied Andrew II on the initial campaign.

- Oliver of Paderborn: A German cleric who led a contingent of German Crusaders.

- William I of Holland: Led a mixed army of Dutch, Flemish, and Frisian soldiers.

- Pelagius Galvani: The papal legate who arrived later and became the de facto leader of the Crusade.

The involvement of these various leaders, each with their own agendas and priorities, would contribute to the leadership squabbles that plagued the Crusade throughout its duration.

The Initial Campaign

The Fifth Crusade began in earnest in September 1217 when Andrew II of Hungary, accompanied by Leopold VI of Austria and Otto I, Duke of Merania, departed from Zagreb. Andrew’s army was impressively large, consisting of some 10,000 mounted soldiers and an even greater number of infantry. The sheer size of the force necessitated that a significant portion remain behind when Andrew and his men embarked from Split two months later.

The Hungarian army, transported by the largest European fleet of the time provided by Venice, landed on Cyprus on October 9, 1217. From there, they made their way to Acre in the Holy Land, where they began planning their attack.

The initial campaign in Syria in late 1217 proved inconclusive. Despite the size and strength of the Crusader army, they failed to make significant headway against the Muslim forces. This lack of progress, combined with other factors, led to the Hungarian King Andrew II’s early departure from the Crusade, leaving the remaining forces to regroup and reconsider their strategy.

The Egyptian Campaign

Following the lackluster results in Syria, the Crusaders shifted their focus to Egypt. This strategic decision was based on the belief that Egypt, then ruled by the Ayyubid dynasty, was the key to ultimately recapturing Jerusalem. The plan was to first conquer the important port city of Damietta, then use it as a base to launch an attack on Cairo, and finally move on to Jerusalem.

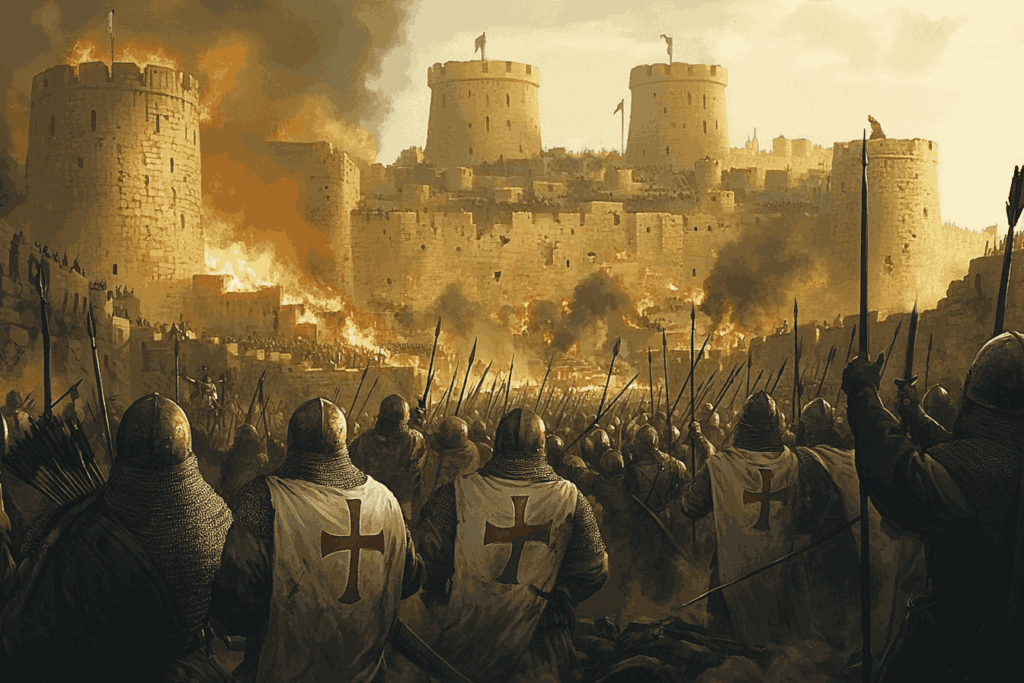

In May 1218, the Crusader army arrived in Egypt and laid siege to Damietta. The city was well-defended, protected by three rings of walls and a formidable tower guarding the harbor. The siege of Damietta would prove to be a long and arduous affair, lasting from June 1218 to November 1219.

Despite the challenges, the Crusaders eventually succeeded in conquering Damietta in November 1219. This victory was a significant achievement and boosted the morale of the Crusader army. However, it also marked the high point of the Fifth Crusade, as things would soon take a turn for the worse.

Internal Strife and Missed Opportunities

Following the capture of Damietta, the Crusaders occupied the port for two years. During this time, internal conflicts and strategic disagreements began to undermine the Crusade’s effectiveness. The lack of a strong, unified leadership became increasingly apparent and problematic.

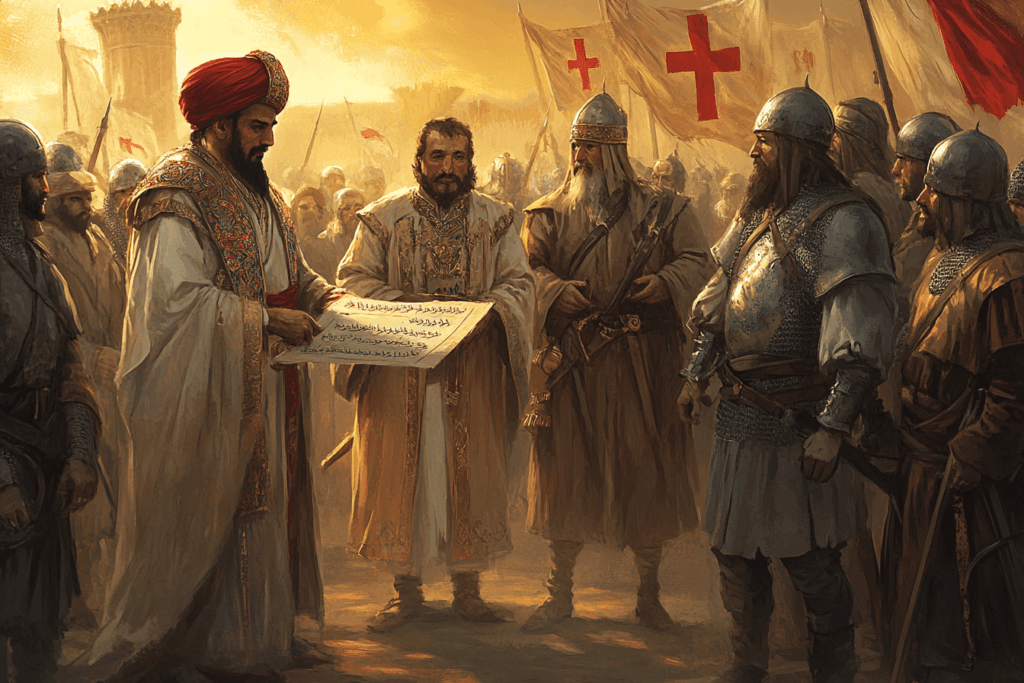

One of the most critical moments of the Crusade came when Al-Kamil, the Sultan of Egypt, offered peace terms to the Crusaders. In an effort to end the conflict and remove the crusaders from Egypt, al-Kamil proposed a generous peace treaty to the Crusaders, offering them control over Jerusalem and much of Palestine, excluding key fortresses like Kerak and Montreal, in exchange for their withdrawal from Egypt. Additionally, al-Kamil would return of the portion of the True Cross lost at the battle of Hattin and release all Christian prisoners. This offer was significant because it would have finally restored much of the territory lost by the Crusaders since Saladin’s conquests.

However, the advantageous offer was rejected by Cardinal Pelagius, the papal legate leading the Crusade, who believed that the arrival of Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II would ensure a military victory, allowing them to capture Egypt and then take Jerusalem by force. This decision would proved costly.

This rejection of Al-Kamil’s peace terms represents one of the great “what-ifs” of the Crusades. Had the Crusaders accepted, they might have achieved their primary objective of recapturing Jerusalem without further bloodshed. Instead, buoyed by their success at Damietta and perhaps overly confident in their abilities, they chose to press on with their campaign.

The March on Cairo

The Crusaders had spent nearly 18 months in relative inactivity, debating their next move, finally, on 7 July 1221, Pelagius ordered the advance southward, despite objections from the more experienced King John of Brienne. The Crusader force, bolstered by recent reinforcements from Germany under Louis I of Bavaria, set out with high hopes of conquering Egypt and, by extension, reclaiming Jerusalem.

The Crusaders made initial progress, occupying the city of Sharamsah on July 12. This early success likely bolstered Pelagius’s confidence, despite continued warnings from King John and other military leaders. The army pushed forward, their sights set on the riches of Cairo and the potential to deal a decisive blow to the Ayyubid Sultanate.

As the Crusaders advanced, they made some critical errors that would soon prove disastrous. The army failed to establish adequate defensive positions as they moved south, making their rear vulnerable. Pelagius’s plan relied on maintaining supply lines with Damietta, but he had not brought sufficient provisions for the entire army. In addition, the Crusaders failed to account for the annual flooding of the Nile, which would soon play a crucial role in their campaign.

By July 24, the Crusader army had reached a position near the Ushmum canal, opposite the city of Mansurah. It was here that Sultan al-Kamil had prepared his defenses, transforming Mansurah into a fortified stronghold.

The sultan, demonstrating superior tactical acumen, had chosen his position wisely. Mansurah was protected by the confluence of a Nile tributary, making it easily defensible. Moreover, al-Kamil had used the time afforded by the Crusaders’ earlier indecision to call for reinforcements from Syria and Mesopotamia.

As July turned to August, the annual rising of the Nile began. This natural phenomenon, so crucial to Egyptian agriculture, would prove to be the Crusaders’ undoing. Al-Kamil, intimately familiar with the terrain and the Nile’s patterns, used this to his advantage.

The sultan’s forces were able to use the rising waters to block the Crusaders’ communication and supply lines with Damietta. Large vessels were brought up from al-Maḥallah through a canal near Barāmūn, effectively cutting off the Crusader army from its base.

Realizing the perilousness of their position, Pelagius ordered a retreat on August 26. However, the Crusaders soon found their path back to Damietta blocked by al-Kamil’s troops. In a last-ditch effort, the Christian army attempted to reach Barāmūn under the cover of darkness, but their lack of stealth alerted the Egyptian forces.

The Final Blow

Al-Kamil delivered the coup de grâce by ordering the opening of the sluices along the right bank of the Nile. This action deliberately flooded the entire area, rendering battle impossible and trapping the Crusader army. The once-mighty Christian force found itself bogged down in waist-deep water, their movements severely hampered.

On 28 August 1221, Cardinal Pelagius was forced to sue for peace, sending an envoy to Sultan al-Kamil. The battle ended in a humiliating Crusader surrender. The defeat was so complete that the Crusaders were unable to secure even symbolic victories, such as the return of the True Cross.

The terms of surrender were as harsh as the offer of peace a few months earlier had been generous. In exchange for safe passage, the Crusaders had to withdraw from Damietta, release all prisoners, and agree to an eight-year truce. On September 8, 1221, the sultan entered Damietta, marking the end of the Fifth Crusade.

The Aftermath and Legacy

The failure of the Fifth Crusade had significant repercussions. It marked the last Crusade organized by the Church in which different nations came together to fight for the recovery of the Holy Land. The rejection of Al-Kamil’s peace offers stands out as a critical strategic error. This decision, driven perhaps by overconfidence or religious zeal, cost the Crusaders their best chance at regaining control of Jerusalem.

In many ways, the Fifth Crusade encapsulates the broader story of the Crusades themselves: a mixture of religious fervor, political ambition, military prowess, and strategic miscalculation. It serves as a reminder of the challenges inherent in mounting large-scale military expeditions in distant lands, and the potential costs of allowing ideology to trump pragmatism in matters of war and peace.

In the annals of history, the Fifth Crusade remains a fascinating chapter of what might have been, a tale of ambition, perseverance, and ultimately, a costly lesson in the art of war and diplomacy in the medieval world.