The Second Crusade (1147–1149) was marked by ambitious goals, dramatic failures, and unforeseen consequences. Launched in response to the fall of the County of Edessa to Muslim Arab and Turk forces in 1144, unlike the First, this crusade was led by European royalty: Louis VII of France and Conrad III of Germany.

Origins and Goals

The immediate catalyst for the Second Crusade was the capture of Edessa by Imad ad-Din Zangi, an Arab ruler who had consolidated power in Mosul and Aleppo. Edessa, the first Crusader state established during the First Crusade (1095–1099), was a vital Christian stronghold on the frontier of the Latin East. Its fall sent shockwaves through Christendom, prompting Pope Eugenius III to issue a call to arms on December 1, 1145. This marked the beginning of what would become a multi-theater campaign aimed at reclaiming Edessa, securing Christian territories in the Levant, and expanding Christendom in other regions such as Iberia and the Baltic.

The Pope’s appeal was bolstered by Bernard of Clairvaux, a charismatic Cistercian abbot whose fiery sermons inspired thousands to take up the cross. Crusaders were promised spiritual rewards, including remission of sins, as well as protections for their families and property during their absence. However, the lack of a clear strategic focus—Edessa was not explicitly named as the primary target—would later contribute to the campaign’s failure.

Leadership and Initial Challenges

For the first time in Crusading history, two reigning monarchs led their armies: Conrad III of Germany and Louis VII of France. Their participation lent prestige to the endeavor but also highlighted deep divisions within Christendom. The two kings spurned the offer from the King of Sicily of naval transport to the Levant (the Holy Lands) and marched separately toward Constantinople in 1147, navigating treacherous political landscapes.

Relations with the Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Komnenos were fraught with mistrust; Western sources accused him of secretly undermining the Crusaders by collaborating with Muslim forces. The Byzantines viewed the crusaders with suspicion due to their reputation for plundering and their perceived designs on Constantinople.

Their Journeys: Louis

Louis VII, deeply pious and eager to fulfill his religious duty, was among the first to take up the cross. His decision was influenced by his desire for spiritual redemption and his long standing plan to make a pilgrimage to Jerusalem.

In June 1147, Louis and his army departed from Metz, accompanied by nobles from across France. Louis’s wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine, brought her court with her, reportedly dressed as Amazons—a spectacle that captured the imagination of chroniclers. The French contingent joined forces with Conrad III of Germany, but tensions simmered between the two leaders. Both armies chose an overland route through Byzantine territory rather than accepting sea passage offered by Roger II of Sicily, whom neither trusted.

While Manuel entertained Louis lavishly in Constantinople, he also signed a truce with the Seljuk Turks, leaving the crusaders vulnerable as they marched into Anatolia.

Trials in Anatolia

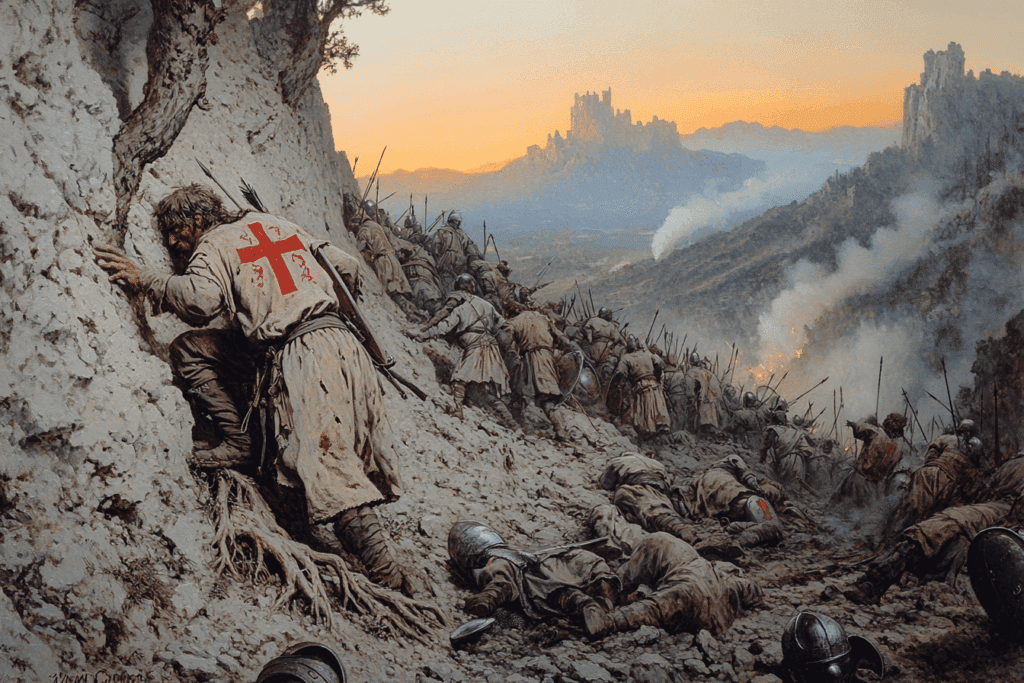

The journey through Anatolia proved disastrous. Conrad’s German army suffered a devastating defeat at the hands of the Seljuks near Dorylaeum in late 1147. Louis’s French forces fared no better. After splitting his army near Laodicea, one contingent was ambushed and annihilated by Turkish forces at Mount Cadmus. The survivors endured relentless attacks as they retreated through treacherous terrain.

Louis himself narrowly escaped death on several occasions. At one point, he reportedly clung to tree roots while scaling rocky paths under fire from Turkish archers. Hunger and desperation plagued his troops; they resorted to eating their own horses—a grim testament to their plight.

By January 1148, what remained of Louis’s army reached Antalya. Here they faced another setback: exorbitant fees demanded by Greek merchants for transport across the Mediterranean. Despite their bitterness towards their Byzantine “allies,” the crusaders had no choice but to pay.

Discord in Antioch

In March 1148, Louis arrived in Antioch, where he was warmly welcomed by Prince Raymond of Poitiers—Eleanor’s uncle. Raymond urged Louis to focus on retaking Edessa, but Louis had other priorities. He sought primarily to complete his pilgrimage to Jerusalem rather than engage in further military campaigns.

The growing estrangement between Louis and Eleanor reached a breaking point in Antioch. Rumors swirled about Eleanor’s alleged closeness to Raymond; some even accused her of an incestuous affair with her uncle. When Eleanor refused to accompany Louis southward to Jerusalem, he forced her hand—an act that only fueled gossip and deepened their marital rift.

Their Journeys: Conrad

Inspired by the words of Bernard of Clairvaux and motivated by religious fervor and political prestige, Conrad pledged to take up the cross. At the imperial diet in Frankfurt in March 1147, he secured support from German nobles for the crusade. Before departing, Conrad ensured his succession by having his son Henry Berengar crowned king, a prudent move to safeguard his dynasty in case of his death during the campaign.

The Journey Begins

Conrad’s army of 20,000 men set out on an overland route through Hungary toward Constantinople. The sheer size of his force caused logistical challenges, particularly as they passed through Byzantine territory. Relations with Emperor Manuel I Komnenos of Byzantium were tense; Manuel viewed the crusaders as unruly foreigners who might disrupt his own campaigns against the Seljuq Turks. Despite these tensions, Conrad reached Constantinople in September 1147.

Rather than waiting for Louis VII’s French army to join him, Conrad decided to cross into Anatolia independently—a decision that would prove disastrous. Driven by pride and a desire for glory, he sought to lead the way through hostile territory rather than taking the safer coastal route around Anatolia.

The Battle of Dorylaeum: A Crushing Defeat

On October 25, 1147, Conrad’s forces encountered the Seljuq Turks at Dorylaeum. The Turks employed hit-and-run tactics that devastated the German army. Most of Conrad’s infantry were killed or captured, leaving only a fraction of his knights to escape. The survivors retreated to Nicaea in disarray, where many deserted and attempted to return home.

Conrad himself fell gravely ill during this retreat. He was transported to Ephesus and later recuperated in Constantinople under the care of Emperor Manuel I Komnenos, who personally attended to him as a physician—a rare moment of cooperation between two leaders often at odds.

After recovering from his illness, Conrad sailed to Acre and eventually reached Jerusalem in early 1148.

The Siege of Damascus

Despite these setbacks, the remnants of both armies eventually reached Jerusalem in 1148. In Jerusalem, Louis joined Conrad III and Baldwin III of Jerusalem for a council on their next move. Instead of targeting Edessa, they decided to attack Damascus—a wealthy city that had previously allied with the Crusader states against rival Muslim factions. This decision has puzzled historians ever since, though it is likely that Damascus’ wealth was the main motivator.

The siege began in July 1148 but quickly unraveled due to poor planning and lack of coordination among the crusaders. After initial successes, they inexplicably shifted their assault from a well-supplied section of Damascus’s defenses to a stronger position. This tactical blunder allowed Arab reinforcements to arrive and forced the crusaders into retreat after just four days.

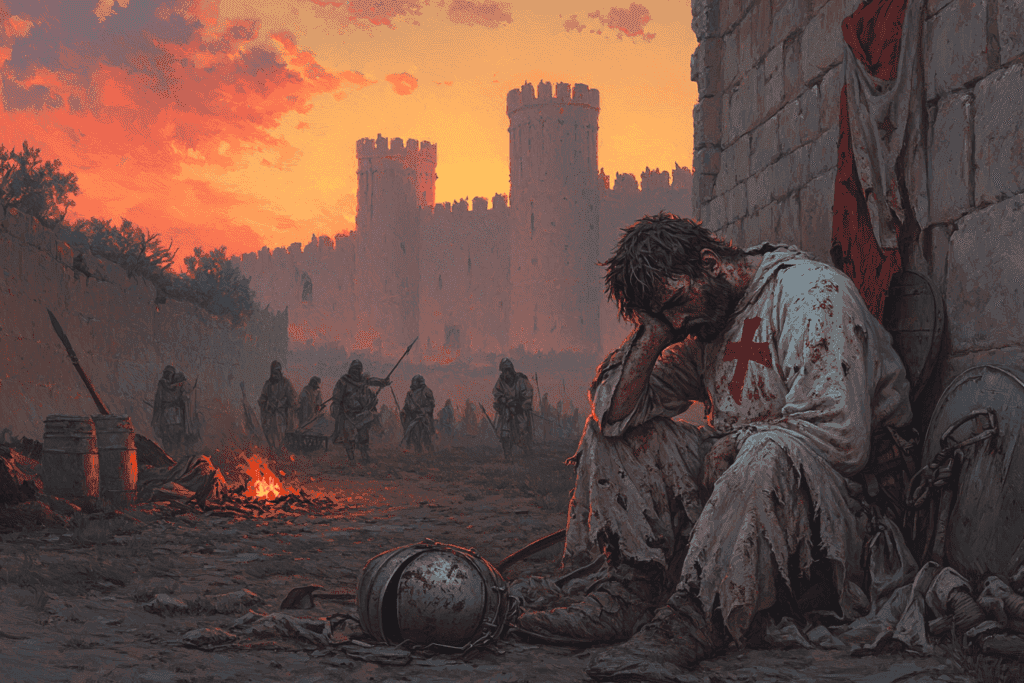

The failure at Damascus marked the end of the Second Crusade in the East. It was a humiliating defeat that shattered Christian morale and emboldened Muslim forces. Disillusioned by this debacle and frustrated with his allies’ lack of support during subsequent plans to attack Ascalon, Conrad decided to return home

The Leaders Return

Conrad’s journey back to Germany was marked by further diplomatic engagements with Manuel I Komnenos in Constantinople. The two emperors renewed their alliance against Roger II of Sicily but could not erase the bitter memories of Byzantine duplicity during the crusade. By late 1149, Conrad was back in Germany, where he resumed his role as king amidst ongoing internal conflicts.

Louis VII returned to France in 1149 with his reputation surprisingly intact. Despite the crusade’s failure, his piety and personal conduct were praised by contemporaries. Clergy attributed the debacle not to Louis but to the sins of others—be it Conrad III, Byzantine duplicity, or lesser lords within the crusading ranks.

His marriage to Eleanor did not survive long after their return. In 1152, their union was annulled on grounds of consanguinity—a convenient pretext that masked deeper issues. Eleanor soon married Henry II of England, creating a powerful rival dynasty that would dominate Anglo-French relations for decades. Louis VII continued his reign as King of France until 1180.

Legacy

The Second Crusade was an unequivocal failure for Christendom. It exposed deep divisions among European leaders and highlighted their inability to cooperate effectively against Muslim forces.

The defeat emboldened Muslim leaders like Nur ad-Din Zangi, who consolidated power in Syria and later paved the way for Saladin’s rise. By 1154, Nur ad-Din had captured Damascus, uniting Syria under his rule.

The crusade deepened mistrust between Byzantium and Western Europe. Accusations that Emperor Manuel I had sabotaged the campaign fueled resentment among Western leaders.

The catastrophic losses demoralized European Christians and dampened enthusiasm for future crusades. It would take nearly four decades before another large-scale expedition—the Third Crusade—was launched.