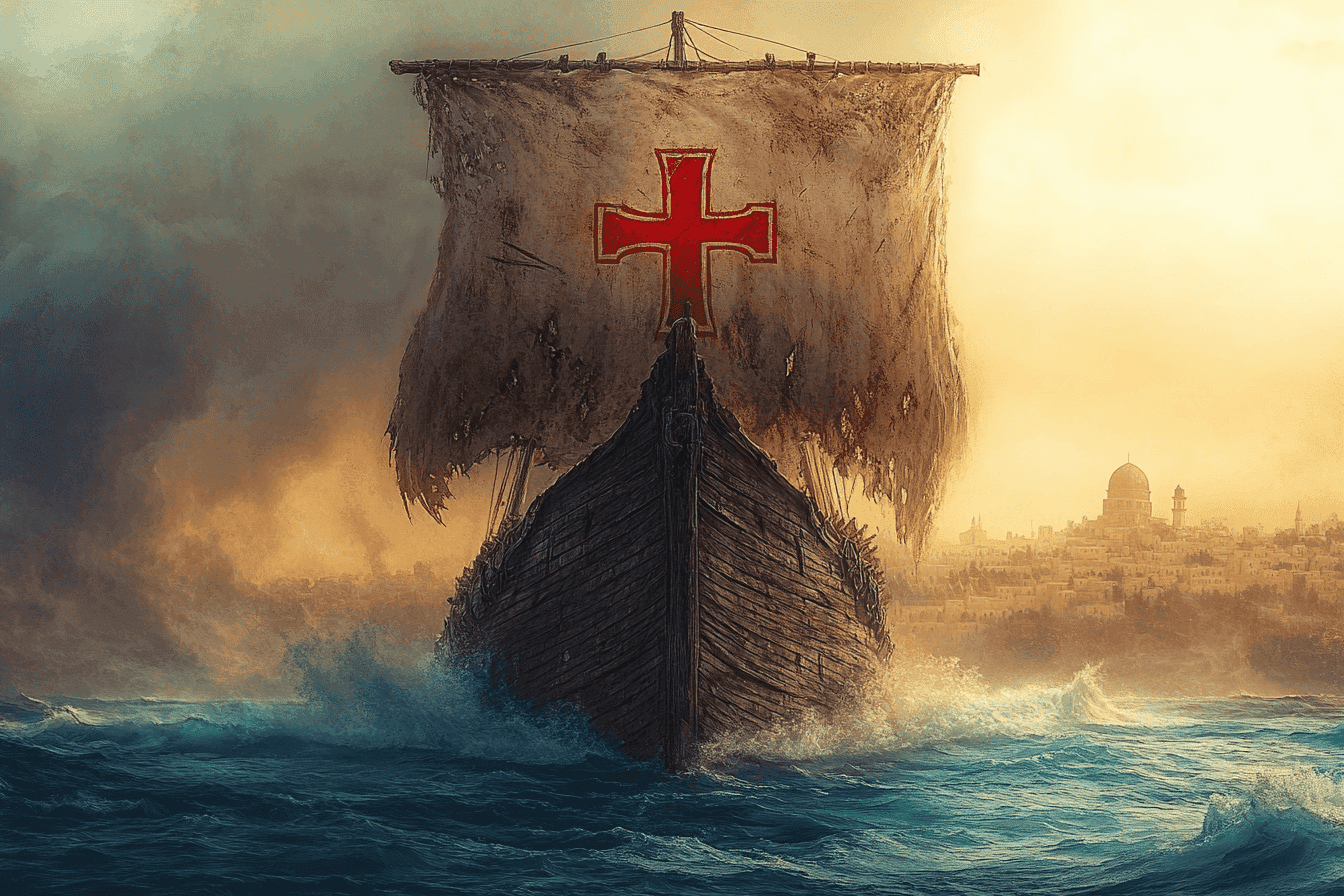

The Eighth Crusade, launched in 1270 CE, stands as a significant yet often overlooked chapter in the history of the Crusades. This military expedition, led by King Louis IX of France, marked the last major crusade aimed at reclaiming the Holy Land. The campaign, ambitious in its goals, would see the death of its leader and ultimately the death of the crusading movement.

Background and Motivations

The Eighth Crusade came about as a response to the declining power of the remaining Crusader states in the Levant. The political landscape of the region had undergone significant changes in the years leading up to 1270. In 1260, Mongol forces under Hulagu Khan had invaded Muslim Syria, capturing key cities such as Aleppo and Damascus. This briefly raised hopes among Christians, as the Mongol general Kitbuqa, himself a Christian, began converting mosques in Damascus into churches.

However, this situation was short-lived. The Egyptian Mamluks, angered by the Mongol presence, successfully assassinated Kitbuqa and forced the Mongols to retreat to Persia. The Mamluks then seized control of Syria, capturing several important towns, including Jaffa and Antakya in 1268. These events alarmed the Christian powers in Europe and prompted King Louis IX to organize the Eighth Crusade in an attempt to reverse these losses and recapture the Holy Land.

Preparations and Participants

King Louis IX, who had previously led the Seventh Crusade (1248-1254 CE), took charge of organizing this new expedition. Despite his earlier failure, Louis remained committed to the crusading ideal and saw this as an opportunity to fulfill his sacred duty as a Christian monarch.

The crusading army was composed of forces from various European nations. King Louis IX of France was the primary leader, but he was joined by other notable figures:

- James I of Aragon, who set off with the first group in June 1269 CE

- Charles of Anjou, who departed in July 1270 CE

- Prince Edward (later Edward I) of England, who sailed in August 1270 CE

The diversity of participants highlighted the international nature of the crusading movement, even in its later stages.

The Campaign Begins

The Eighth Crusade set sail for the Middle East in stages, with different contingents departing at various times. Unfortunately, the expedition faced challenges from the outset. The first group, led by James I of Aragon, encountered a devastating storm that severely hampered their progress.

Rather than heading directly to the Holy Land, the crusaders decided to target Tunis in North Africa. This decision was influenced by several factors:

- The strategic location of Tunis as a potential base for further operations

- The belief that the ruler of Tunis might be open to conversion to Christianity

- The commercial interests of Charles of Anjou in the region

The choice of Tunis as the initial target marked a significant departure from previous crusades, which had typically focused on Syria and Egypt.

The Siege of Tunis

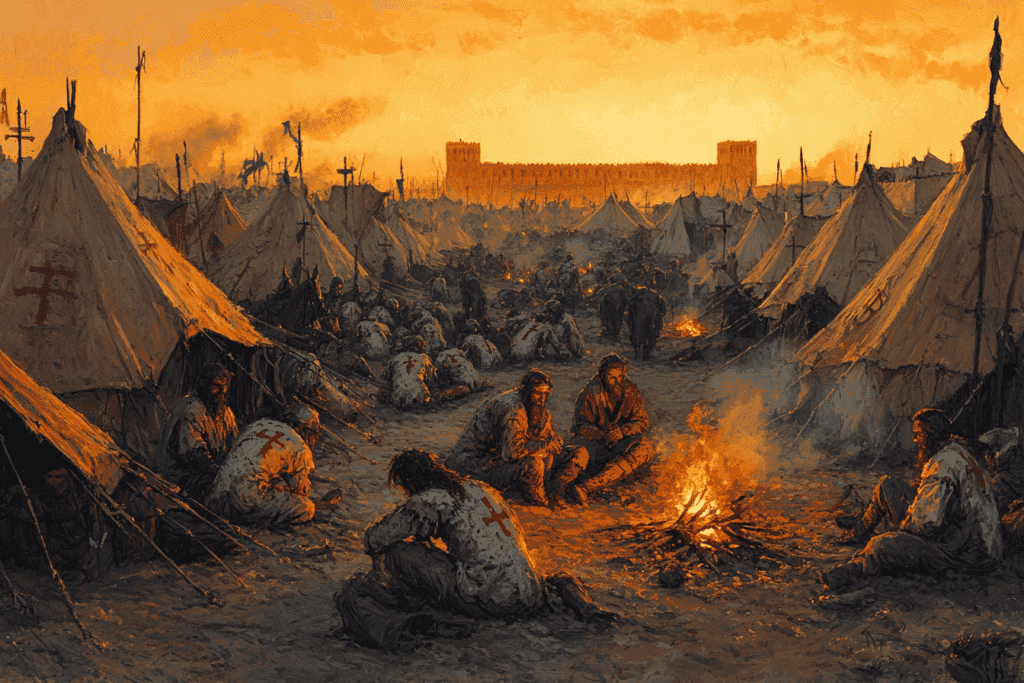

In July 1270, the crusader army arrived on the shores of Tunisia and began their campaign against the Hafsid dynasty. The Christian forces posed a serious threat to the Hafsid regime, led by al-Mustanṣir (r. 1249–77). The crusaders established a beachhead and prepared for a siege of the city of Tunis.

However, the campaign quickly ran into difficulties. The summer heat of North Africa proved to be a formidable enemy, and disease began to spread through the crusader camp. The Muslim defenders of Tunis, while under pressure, managed to hold out against the initial assaults.

The Death of Louis IX

The turning point of the Eighth Crusade came with a tragic event. On August 25, 1270, King Louis IX succumbed to dysentery. The death of the crusade’s primary leader and spiritual figurehead dealt a devastating blow to the morale and organization of the Christian forces.

Louis IX’s death marked the end of an era in many ways. He had been one of the most prominent advocates of crusading in the 13th century, and his passing symbolized the declining enthusiasm for such expeditions among European monarchs.

The Aftermath and Treaty of Tunis

Following the death of Louis IX, the remaining crusader leaders were forced to reassess their position. Charles of Anjou, who arrived shortly after Louis’s death, took charge of negotiations with the Hafsid ruler. The result was the Treaty of Tunis, which brought an end to the military campaign. The terms of the treaty included:

- No territorial changes

- Commercial rights granted to Christian merchants

- Some political concessions to the crusaders

While the treaty fell far short of the crusaders’ initial goals, it did secure some benefits for Christian interests in the region.

Prince Edward’s Continuation

Although the main force of the Eighth Crusade withdrew after the Treaty of Tunis, one notable figure chose to continue the campaign. Prince Edward, then 31 years old, had committed to join the crusade. However, his departure was delayed due to domestic matters in England. By the time Edward’s fleet set sail from England in August 1270, the main crusader force had already landed in Tunisia.

When Edward finally arrived off the coast of Tunisia on November 9, 1270, he was met with unexpected news. Louis IX had died of dysentery shortly after landing, and the French army, now led by Philip III, had negotiated a treaty with the Hafsids and was preparing to return home.

Edward faced a difficult decision. The main crusader force was disbanding, and he had arrived too late to participate in any significant action. However, Edward was determined to fulfill his crusader vow and continue to the Holy Land.

The Ninth Crusade

After a brief stay in Sicily, where the crusader fleet had been badly damaged by a storm, Edward resolved to press on. In April 1271, he set sail for Acre with a relatively small force of about 1,000 men, including 225 knights.

Edward’s arrival in Acre on May 9, 1271, marked the beginning of what is often called the Ninth Crusade or Lord Edward’s Crusade. Although his force was small, Edward’s presence brought hope to the beleaguered Crusader states, which were under constant threat from the Mamluk Sultan Baibars.

Edward’s crusade saw limited military action. He conducted several raids against nearby Muslim positions and attempted to coordinate with the Mongols, who were also enemies of the Mamluks. However, Edward’s force was too small to engage in any major battles or sieges.

One of Edward’s most significant achievements was negotiating a ten-year truce with Sultan Baibars in 1272. This agreement provided a temporary respite for the Crusader states and allowed Edward to return home with a sense of accomplishment.

Assassination Attempt

Edward’s crusade was not without personal danger. In June 1272, he survived an assassination attempt by a member of the Assassin sect. Edward was wounded in the arm by a poisoned dagger but managed to kill his attacker. Legend has it that Edward’s wife, Eleanor of Castile, sucked the poison from his wound, though this romantic tale is likely apocryphal.

Return to England

Edward left Acre in September 1272, bringing an end to his crusade. During his return journey, he learned that his father, Henry III, had died, making him the new King of England. Edward took his time returning home, finally arriving in England in 1274 to claim his crown.

The End of an Era

The Eighth Crusade is often seen as the last gasp of the traditional crusading movement. Although there would be future calls for crusades, none would match the scale or significance of the earlier expeditions.

The year 1291 saw the fall of Acre, the last remaining crusader stronghold in Palestine, effectively bringing an end to the crusading era in the Holy Land. The dream of a Christian-controlled Jerusalem, which had inspired generations of European knights and pilgrims, had finally faded.