The First Crusade, launched in 1095, was a watershed moment that reshaped the political and religious landscape of Europe and the Middle East. This military expedition, called for by Pope Urban II, aimed to recapture Jerusalem and the Holy Land from Muslim control. It marked the beginning of a series of religious wars that would span centuries and have far-reaching consequences for Christian-Muslim relations.

Origins and Call to Arms

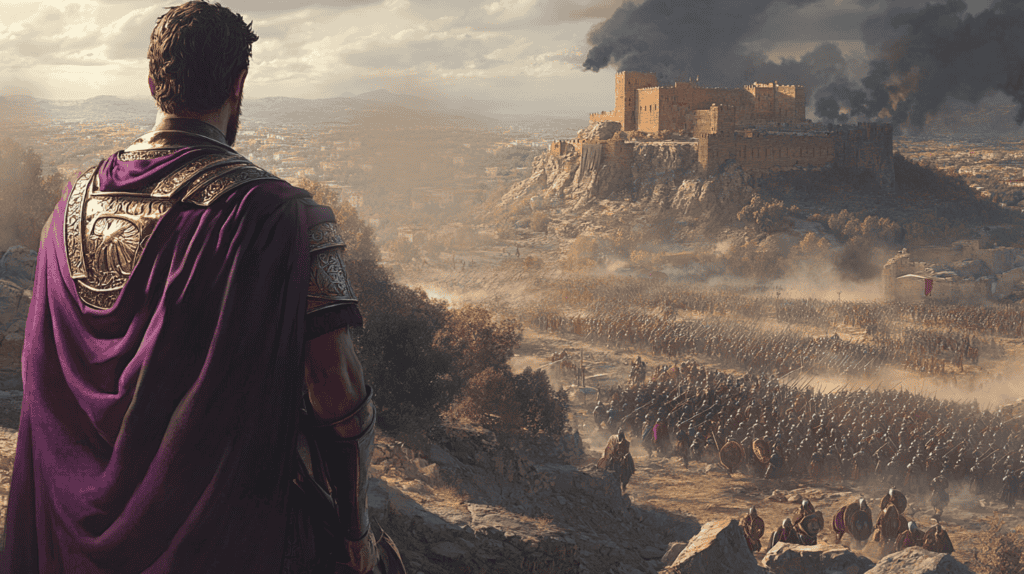

The roots of the First Crusade can be traced to the complex geopolitical situation of the late 11th century. By this time, approximately two-thirds of the ancient Christian world had been conquered by Muslim forces, including the important regions of Palestine, Syria, Egypt, and Anatolia. The Byzantine Empire, the eastern remnant of the Roman Empire, found itself under increasing pressure from the Seljuk Turks, who had made significant inroads into Byzantine territory.

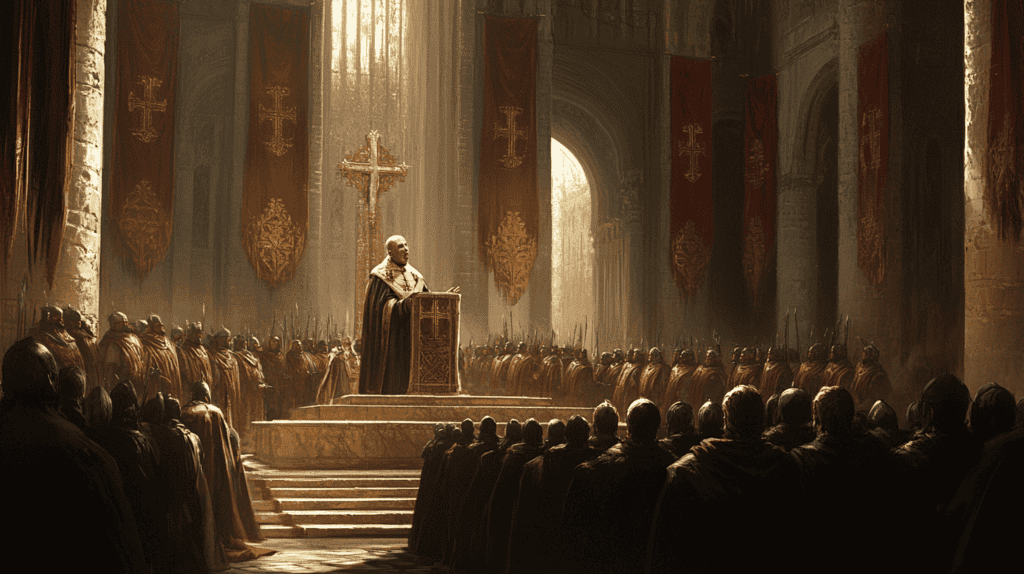

In 1095, Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos appealed to Pope Urban II for military assistance against the advancing Seljuks. This request coincided with the pope’s own desire to assert papal authority and unite the Christian world under his leadership. On November 27, 1095, at the Council of Clermont in France, Pope Urban II delivered a rousing sermon that would ignite the flames of crusading fervor across Western Europe.

Urban’s call to arms was a masterful piece of rhetoric that appealed to various motivations: the pope promised absolution of sins and eternal glory to those who participated in the crusade, for knights and warriors, the crusade offered an opportunity for glory and conquest, and the prospect of acquiring land and wealth in the East was attractive to many.

The response to Urban’s call was overwhelming. Across Europe, from all social strata, people took up the cross and prepared for the journey to Jerusalem.

The People’s Crusade

Before the main crusading armies could be organized, a popular movement known as the People’s Crusade set out in April 1096. Led by the charismatic preacher Peter the Hermit, this group consisted of around 30,000 people, many of whom were peasants and non-combatants.

The People’s Crusade was ill-prepared and poorly disciplined. As they made their way across Europe, they engaged in violence against Jewish communities, particularly in the Rhineland. This marked the beginning of a tragic pattern of anti-Semitic violence that would be associated with the Crusades.

The People’s Crusade met a disastrous end in October 1096 when they were crushed by the Seljuk Turks at the battle of Civetot, southeast of Constantinople.

In the lead-up to the battle, Turkish spies spread a rumor that the German contingent of the crusaders had captured Nicaea. This false information excited the main camp of crusaders at Civetot, who were eager to share in the supposed spoils. Despite warnings to wait for Peter the Hermit’s return from Constantinople, where he had gone to arrange supplies, the crusaders decided to march towards Nicaea under the leadership of Geoffrey Burel.

On the morning of October 21, an army of about 20,000 crusaders set out, leaving behind women, children, the elderly, and the sick at their camp. The Turkish forces of Sultan Kilij Arslan I were waiting in ambush about three miles from the camp, where the road entered a narrow, wooded valley near the village of Dracon. As the crusaders approached the valley, making considerable noise, they were suddenly subjected to a hail of arrows from the hidden Turkish archers. Panic immediately set in, and within minutes, the entire crusader army was in full retreat back to their camp.

The battle quickly turned into a massacre. Most of the crusaders were slaughtered, while women and children who had been left behind at the camp were not spared. Only young girls and boys who could be sold as slaves were taken alive.

A small group of about 3,000 crusaders, including Geoffrey Burel, managed to find refuge in an abandoned castle. Eventually, Byzantine forces under Constantine Katakalon arrived by sea and rescued these survivors, who were then transported back to Constantinople.

The Battle of Civetot effectively ended the People’s Crusade. It demonstrated the dangers of poor organization, lack of military discipline, and underestimation of the enemy. The few survivors of this disaster later joined the more organized and better-equipped Princes’ Crusade, with Peter the Hermit taking a subordinate role in the new army.

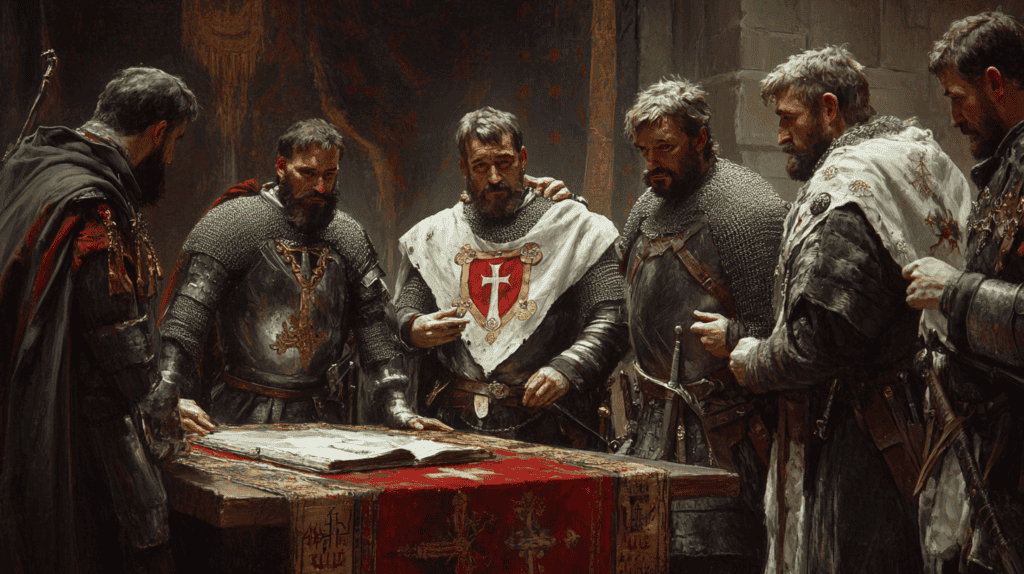

The Princes’ Crusade

The main crusading army, often referred to as the Princes’ Crusade, began to assemble in late 1096. This force was led by several prominent nobles, including:

Godfrey of Bouillon, Duke of Lower Lorraine

Bohemond of Taranto, a Norman prince from southern Italy

Raymond IV, Count of Toulouse

Robert of Normandy, brother of King William II of England

These leaders brought with them contingents of knights and foot soldiers, forming a formidable military force. The crusaders gathered outside Constantinople between November 1096 and April 1097.

The Byzantine Connection

The arrival of the crusaders at Constantinople created a complex political situation. Emperor Alexios I Komnenos had expected Western assistance, but the scale and ambition of the crusading army took him by surprise. He was wary of the crusaders’ intentions and sought to ensure their loyalty to the Byzantine Empire.

Alexios required the crusade leaders to swear an oath of fealty, promising to return any former Byzantine territories they might recapture. This arrangement would later be a source of tension between the Byzantines and the crusaders.

The March to Jerusalem

The Siege of Nicaea

The first major military engagement of the First Crusade was the siege of Nicaea, which lasted from May 14 to June 19, 1097. Nicaea, located in northwestern Anatolia, was the capital of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum. The crusaders, with Byzantine support, successfully besieged the city, forcing its surrender to the Byzantine Empire.

The Battle of Dorylaeum

On July 1, 1097, the crusaders faced their first major field battle at Dorylaeum. A crusader contingent was ambushed by Seljuk forces but was relieved by the main army, resulting in a decisive victory for the crusaders. This battle demonstrated the military prowess of the Western knights and boosted the crusaders’ morale.

The Siege of Antioch

The crusaders reached Antioch in October 1097, beginning a grueling eight-month siege that would test their resolve. Antioch, a strategically important city, was well-fortified and defended. The siege was marked by hardship and near-starvation for the crusaders.

The tide turned when Bohemond of Taranto negotiated with a guard inside the city to open a gate. On June 3, 1098, the crusaders entered Antioch, massacring many of its inhabitants, including Christians of the Greek Orthodox, Syrian, and Armenian communities.

However, the crusaders’ position remained precarious. Shortly after taking the city, they found themselves besieged by a large Muslim army led by Kerbogha, the ruler of Mosul. In a dramatic turn of events, the crusaders, inspired by the alleged discovery of the Holy Lance, sallied forth and defeated Kerbogha’s forces on June 28, 1098.

The March to Jerusalem

After the victory at Antioch, disputes arose among the crusade leaders. Bohemond claimed Antioch for himself, while Raymond of Toulouse pushed for a quick march to Jerusalem. Eventually, the army moved south, reaching the walls of Jerusalem in June 1099.

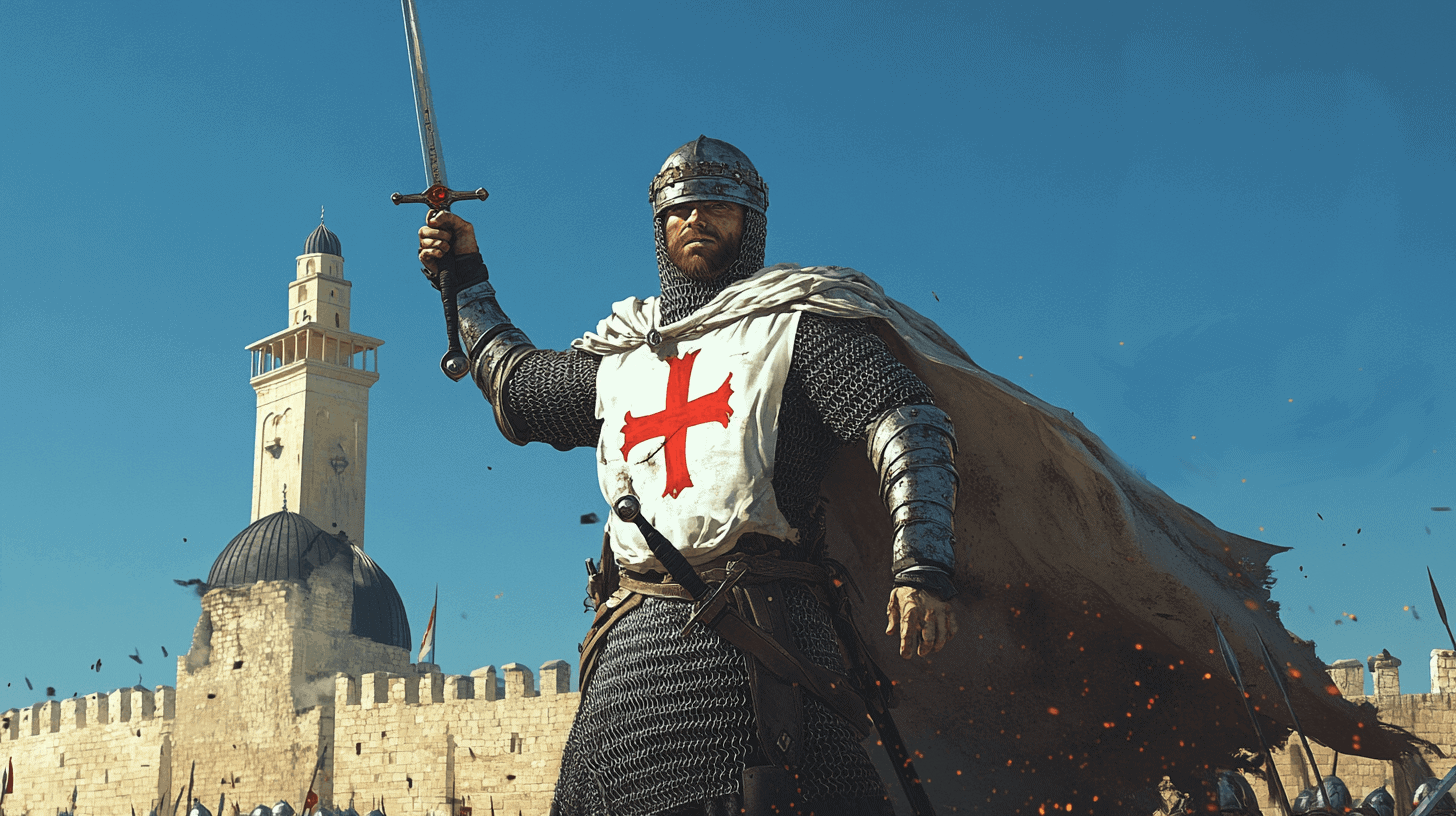

The Siege of Jerusalem

The siege of Jerusalem began on June 7, 1099. The crusaders, numbering around 12,000 fighting men, faced a well-fortified city defended by a Fatimid garrison. The siege was challenging, with the crusaders lacking proper siege equipment and suffering from water shortages.

The arrival of Genoese ships at Jaffa with supplies and craftsmen turned the tide. Two large siege towers were constructed, and on July 15, 1099, the crusaders breached the city walls. What followed was a brutal sack of the city, with crusader chronicles describing widespread massacre of the inhabitants, both Muslim and Jewish.The narrative of the massacre at Jerusalem became a powerful symbol, both of crusader triumph for Christians and of barbarity for Muslims.

Aftermath and Establishment of the Crusader States

In the wake of the First Crusade, the victorious crusaders established four Christian states in the Levant: The Kingdom of Jerusalem, The Principality of Antioch, The County of Edessa and The County of Tripoli. These Crusader States would become the focus of future crusades and conflicts in the region.

Godfrey of Bouillon, who had played a crucial role in the siege of Jerusalem, was chosen to rule the newly established Kingdom of Jerusalem. He took the title “Defender of the Holy Sepulchre,” refusing to be crowned king in the city where Christ had worn a crown of thorns.

The First Crusade concluded with the Battle of Ascalon on August 12, 1099. Godfrey led the crusader forces to victory against a Fatimid army from Egypt, securing the Frankish position in the Holy Land.

Legacy and Impact

The First Crusade had profound and lasting impacts on both Europe and the Middle East. It established a Western Christian presence in the Levant that would last, in various forms, until the fall of Acre in 1291. The Crusade strengthened papal authority and the concept of “holy war” in Western Christianity, but intensified religious and cultural conflict between Christians and Muslims, creating lasting animosities and setting a precedent for future crusades, both to the Holy Land and against other perceived enemies of the Church.