The Fourth Crusade, which took place from 1202 to 1204 CE, stands as one of the most controversial and consequential events in medieval history. What began as a noble mission to recapture Jerusalem from Muslim control took a shocking and unexpected turn, culminating in the sack of Constantinople, the capital of the Christian Byzantine Empire. This event not only reshaped the political landscape of the Eastern Mediterranean but also left an indelible mark on the relations between Eastern and Western Christianity.

Origins and Initial Plans

In 1198, Pope Innocent III ascended to the papacy with grand ambitions to unite Christendom and reclaim the Holy Land. He called for a new crusade, aiming to retake Jerusalem, which had fallen to Muslim forces in 1187. The crusaders, however, devised a strategy that differed from previous expeditions. Instead of attacking Jerusalem directly, they planned to strike at Egypt first, viewing it as a key power in the Muslim world whose defeat would weaken control over Jerusalem.

To execute this ambitious plan, the crusaders needed a formidable naval force. They turned to Venice, the preeminent maritime power of the time, to provide transportation for their army. The Venetians, led by the elderly but shrewd Doge Enrico Dandolo, agreed to build a massive fleet in exchange for a substantial payment.

The First Diversion: Zara

The crusaders’ financial woes began when fewer men arrived in Venice than expected. The agreement between the Venetians and the crusaders had set the date for the arrival of the host in Venice before the end of April 1202, with plans for a summer departure at the end of June. However, many crusaders were delayed, some chose alternative routes, and others simply failed to show up. As a result, only about 12,000 crusaders arrived in Venice, far short of the expected numbers.

Faced with this shortfall, the crusade leaders found themselves in a desperate situation. They had managed to scrape together only 51,000 marks, leaving them deeply indebted to the Venetians. The crusaders pledged their gold and silver plate to Venetian moneylenders, but it was not enough. It was at this critical juncture that the Venetians proposed a controversial solution: in lieu of full payment, the crusaders would assist Venice in recapturing the rebellious city of Zara.

This proposal placed the crusaders in a moral quandary. Attacking a Christian city went against the very principles of the crusade and drew harsh criticism from Pope Innocent III. Nevertheless, driven by desperation and the need to maintain their alliance with Venice, the crusaders agreed to this diversion.

Papal Opposition and Crusader Division

Pope Innocent III, upon learning of the planned attack, was vehemently opposed. He sent letters to Venice forbidding the action and even threatened excommunication for those who participated. The Pope’s stance created a rift among the crusaders. A significant number, led by Simon of Montfort, refused to take part in the siege, viewing it as a betrayal of their crusading vows.

Despite the papal threats and the moral qualms of some crusaders, the majority of the army agreed to the Venetian proposal. They justified their decision by citing the necessity of the action to achieve the larger goal of reaching Jerusalem. This rationalization would have far-reaching consequences for the entire crusade.

The Assault on Zara

The crusader fleet set sail from Venice in early October 1202, arriving at Zara on November 10. The sight of the massive crusader army must have been terrifying for the inhabitants of Zara. The city, though well-fortified, was vastly outnumbered by the combined forces of the crusaders and Venetians.

On November 13, the attackers began their assault. Siege engines were positioned and used to bombard the city’s walls. The defenders of Zara, despite being fellow Christians, fought bravely against the onslaught. However, the outcome was almost inevitable given the disparity in forces.

After two weeks of intense siege and assault, Zara surrendered on November 24, 1202. The fall of the city marked a dark day in crusader history – it was the first time a Catholic army had conquered a Catholic city in the name of a crusade.

The capture of Zara led to widespread violence between the Frankish crusaders and the Venetians over the distribution of plunder, with around 100 people died in the ensuing brawl.

Papal Reaction and Excommunication

Pope Innocent III’s reaction to the sack of Zara was swift and severe. In 1203, he excommunicated the entire crusading army, along with the Venetians, for their part in the attack. This excommunication was a serious matter, effectively cutting off the crusaders from the spiritual benefits and protections of the Church. However, the Pope’s authority was not absolute, and the practical necessities of the crusade soon forced a compromise. In February 1203, Innocent III rescinded the excommunications against all non-Venetians in the expedition, allowing the crusade to continue, albeit under a cloud of moral ambiguity.

Winter in Zara and the Road to Constantinople

Following the capture of Zara, the crusader army wintered in the conquered city, and there an unexpected opportunity presented itself. Alexios Angelos, the son of the deposed Byzantine emperor Isaac II, approached the crusade leaders with an enticing offer. He promised substantial financial rewards and military support for their campaign in the Holy Land if they would help him reclaim the Byzantine throne.

This proposal was met with mixed reactions among the crusaders. Some saw it as a further distraction from their primary goal, while others viewed it as a means to secure the resources needed for their ultimate objective. After much debate, the crusaders decided to accept Alexios’s offer, setting the stage for their fateful encounter with Constantinople.

The Siege of Constantinople: 1203

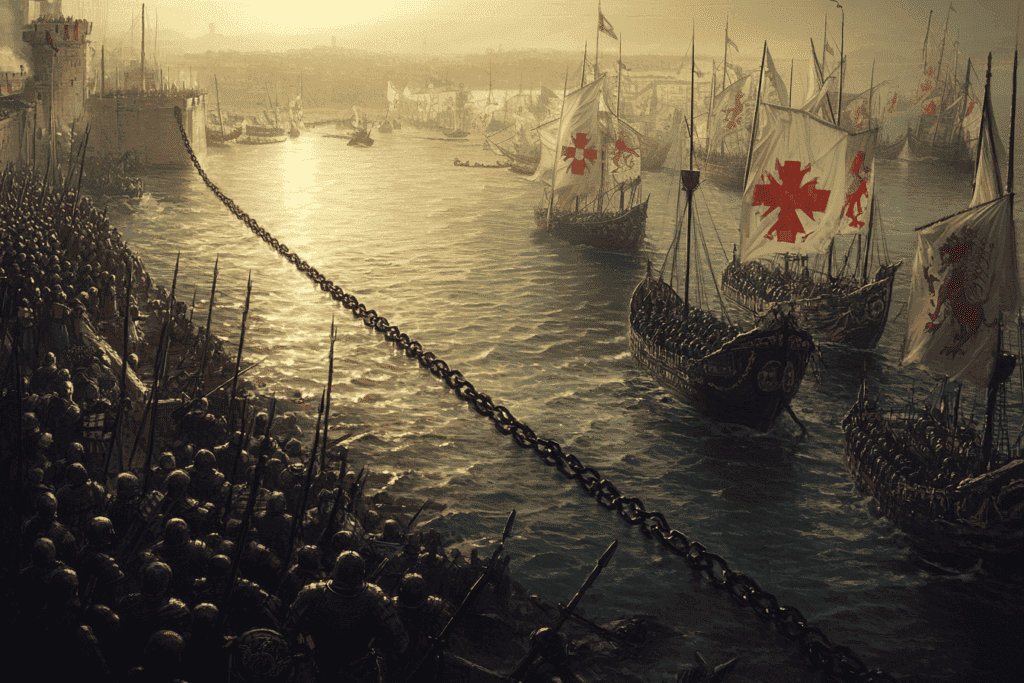

In June 1203, the crusader fleet arrived at the magnificent walls of Constantinople. The city, with its population of approximately 500,000 and a garrison of 15,000 men (including 5,000 elite Varangian Guards), presented a formidable challenge.

The crusader army, comprising around 4,500 knights, up to 14,000 infantry, and 20,000-30,000 Venetians, and its first objective was the Byzantine garrison at Galata, which controlled the chain blocking the entrance to the Golden Horn harbor.

The crusaders employed a combination of naval and land-based tactics: ships were equipped with siege engines and scaling ladders to attack the sea walls, while traditional siege engines were constructed to assault the formidable Theodosian Walls.

Political Maneuvers

The crusaders initially succeeded in their mission to restore Isaac II to the throne, with his son Alexios IV becoming co-emperor. However, this arrangement proved short-lived and unstable. Alexios IV soon realized that the Byzantine treasury could not cover the enormous sum promised to the crusaders. This financial shortfall, combined with growing anti-Latin sentiment among the Byzantine population, created a volatile situation.

The Coup and Escalation

As months passed without payment, relations between the crusaders and the Byzantines deteriorated rapidly. In January 1204, tensions reached a boiling point. A popular uprising in Constantinople led to the overthrow and murder of Alexios IV, and the ascension of Alexios V Doukas to the throne.

The new emperor adopted a hostile stance towards the crusaders, refusing to honor the agreements made by his predecessor. This turn of events left the crusade leaders feeling betrayed and facing a dire situation. With their supplies dwindling and no prospect of payment, they made the fateful decision to attack Constantinople once again, this time with the intent of conquering the city outright.

On April 12, 1204, the crusaders launched their final assault on Constantinople. They breached the city’s defenses through a combination of tactics: a naval assault with men climbed the masts of ships and used catwalks to reach the tops of the city walls while other crusaders broke through a bricked-up gateway, creating an entry point for their forces.

The Fall of Constantinople

What followed was three days of unrestrained violence and looting that would shock the medieval world and leave an enduring scar on the relations between Eastern and Western Christianity.

The crusaders, driven by a combination of greed, religious fervor, and pent-up frustration, unleashed a wave of destruction upon the greatest city in Christendom. Churches, monasteries, and palaces were pillaged. Priceless works of art and holy relics were either destroyed or carried off as loot. The great cathedral of Hagia Sophia, the spiritual heart of Eastern Christianity, was desecrated, its altar smashed and its treasures stolen.

The civilian population suffered greatly during the sack. Niketas Choniates, a Byzantine historian who witnessed the events, described scenes of rape, murder, and wanton destruction. He wrote, “The Latin soldiery subjected the greatest city in Europe to an indescribable sack. For three days they murdered, raped, looted and destroyed on a scale which even the ancient Vandals and Goths would have found unbelievable.”

The Aftermath and Legacy

The consequences of the Fourth Crusade and the sack of Constantinople were far-reaching and long-lasting. The Byzantine Empire, once the bulwark of Eastern Christianity and the inheritor of Roman civilization, was shattered. A Latin Empire was established in Constantinople, with Baldwin of Flanders crowned as emperor in the desecrated Hagia Sophia.

The Byzantine territories were divided among the crusaders and the Venetians, fragmenting the once-mighty empire into a patchwork of Latin-controlled states and Byzantine successor kingdoms. The Empire of Nicaea, established by Byzantine nobles in exile, would eventually recapture Constantinople in 1261 and restore the Byzantine Empire, but it would never regain its former power and glory.

The sack of Constantinople had profound implications for the balance of power in the Eastern Mediterranean. The weakening of the Byzantine Empire left a power vacuum that would eventually be filled by the rising Ottoman Turks. In this sense, the Fourth Crusade, intended to strengthen Christendom’s position against Islam, ultimately contributed to the later Muslim conquest of southeastern Europe.

The cultural and artistic losses inflicted during the sack were immeasurable. Constantinople had been a repository of ancient Greek and Roman knowledge and a center of artistic production for centuries. Countless manuscripts, works of art, and architectural treasures were lost forever. Some treasures, like the famous bronze horses from the Hippodrome, were carried off to adorn Western cities – the horses still stand today on the façade of St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice.

The Fourth Crusade and the sack of Constantinople in 1204 stand as a cautionary tale of how noble intentions can go disastrously awry. What began as a mission to liberate Jerusalem ended with the conquest and devastation of the greatest Christian city in the world. As we reflect on these events more than eight centuries later, the Fourth Crusade serves as a stark reminder of the dangers of allowing political expediency and short-term gains to overshadow stated principles and long-term consequences.