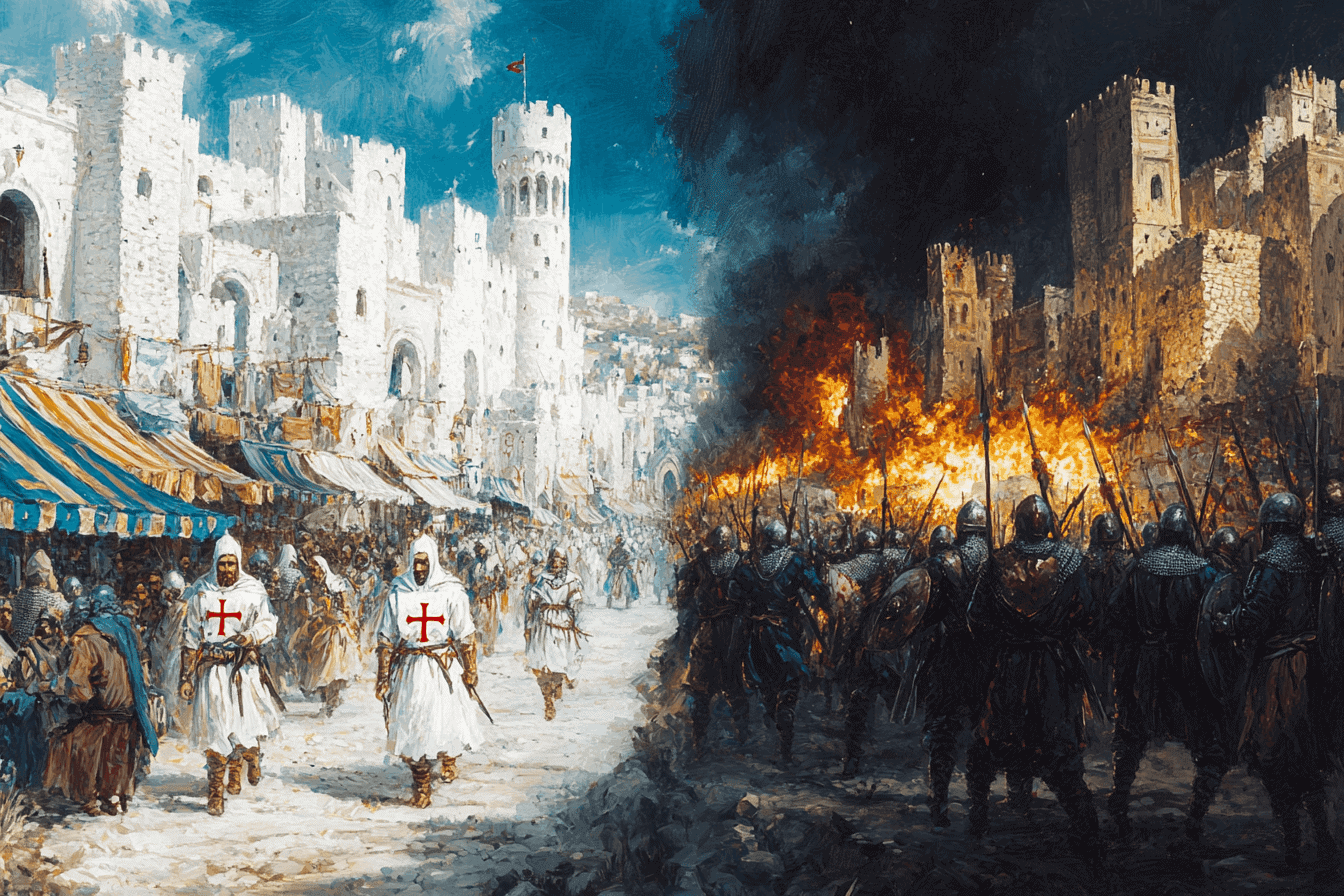

The Fall of Edessa in 1144 was a pivotal event in the history of the Crusades, marking the beginning of the end for the first Crusader state and ultimately leading to the launch of the Second Crusade. This significant turning point in the struggle between Christian and Muslim forces in the Holy Land unfolded against a backdrop of political instability, strategic miscalculations, and the rise of a formidable Muslim leader.

Background and Context

The County of Edessa, established in 1098 during the First Crusade, was the first of the Crusader states to be founded. Located in what is now south eastern Turkey, it was the most northerly, weakest, and least populated of the Crusader territories. Its strategic importance lay in its role as a buffer between the other Crusader states and the Muslim powers to the east and north.

From its inception, Edessa faced frequent attacks from surrounding Muslim states ruled by the Artuqids, Danishmends, and Seljuk Turks. Its leaders, including Count Baldwin II and Joscelin of Courtenay, were captured in 1104, while the latter was killed in battle in 1131.

By 1143, the geopolitical landscape had shifted significantly. The deaths of both Byzantine Emperor John II Comnenus and King Fulk of Jerusalem that year left power vacuums that would have far-reaching consequences. The new rulers, Manuel I Comnenus in Constantinople and Queen Melisende with her young son Baldwin III in Jerusalem, were preoccupied with consolidating their own positions, leaving Edessa increasingly isolated.

The Rise of Zengi

The fall of Edessa cannot be understood without considering the rise of Imad ad-Din Zengi, the atabeg (governor) of Mosul and Aleppo. Zengi had been steadily building his power base since the late 1120s, creating a formidable bloc centered on these two important cities. His strategic vision and military prowess made him a significant threat to the Crusader states.

Zengi’s rise to power was marked by several key developments:

- Capture of Aleppo in 1128, expanding his influence in northern Syria

- Consolidation of power through alliances and military campaigns

- Exploitation of divisions among both Christian and Muslim rulers in the region

By 1144, Zengi had positioned himself as the most powerful Muslim ruler in the region, with his sights set on further expansion.

The Siege of Edessa

The events leading to the siege of Edessa began to unfold in late 1144. Count Joscelin II of Edessa, seeking to counter Zengi’s growing power, formed an alliance with Kara Arslan, the Artuqid ruler of Diyarbakır. This decision would prove to be a critical miscalculation.

On November 28, 1144, while Joscelin II and the bulk of his army were away supporting Kara Arslan against Aleppo, Zengi seized the opportunity to attack Edessa. The city, though warned of Zengi’s approach, was ill-prepared for a prolonged siege without its main defensive force.

The defense of Edessa was left in the hands of:

- Latin Archbishop Hugh of Edessa

- Armenian Bishop John

- Jacobite Bishop Basil bar Shumna

These religious leaders worked to maintain the loyalty of the city’s diverse Christian population and organize the defense.

Zengi’s siege tactics were comprehensive and relentless: he completely encircled the city, reinforcing his forces with Kurdish and Turcoman troops. He built siege engines to batter the walls and also conducted mining operations to try to bring the walls down from below.

The defenders, lacking experience in siege warfare, struggled to mount an effective resistance. Their inability to defend the city’s towers and counter Zengi’s mining operations proved particularly costly.

As news of the siege reached the other Crusader states, Queen Melisende of Jerusalem dispatched a relief force led by Manasses of Hierges, Philip of Milly, and Elinand of Bures. However, this aid would arrive too late to save the city.

The Fall of Edessa

After nearly a month of intense siege, Edessa’s defenses finally crumbled on December 24, 1144. A section of the wall near the Gate of the Hours collapsed after a successful mining operation, allowing Zengi’s troops to pour into the city. The ensuing chaos was marked by widespread violence and panic:

- Thousands of inhabitants were killed in the initial assault

- Many more were trampled to death in the rush to reach the citadel

- Archbishop Hugh was among those killed in the mayhem

Zengi, demonstrating both strategic pragmatism and a degree of mercy, ordered an end to the massacre. While Latin prisoners were executed, the native Christian population was allowed to live freely under Muslim rule. The citadel, the last holdout of resistance, surrendered two days later on December 26.

Immediate Aftermath

The fall of Edessa sent shockwaves through the Crusader states and beyond. Zengi’s victory was hailed throughout the Islamic world, earning him the titles of “defender of the faith” and “al-Malik al-Mansur” (the victorious king).

In the weeks following the city’s capture, Zengi consolidated his gains by appointing Zayn ad-Din Ali Kutchuk as governor of Edessa and Bishop Basil as leader of the Christian population. Zengi pushed on, capturing Saruj in January 1145 and had begun a siege of Birejik when he was interrupted by the arrival of Jerusalemite forces.

Joscelin II, having failed to defend Edessa, retreated to Turbessel, from where he continued to rule the remnants of the county west of the Euphrates. However, the loss of Edessa proper dealt a severe blow to Crusader power in the region.

Long-term Consequences

The fall of Edessa had far-reaching consequences that would reshape the political and military landscape of the Holy Land:

The loss of Edessa removed a crucial buffer zone, exposing the other Crusader territories to increased Muslim pressure. Zengi’s victory emboldened Muslim forces and undermined the psychological advantage the Crusaders had held since the First Crusade. Zengi’s success paved the way for the emergence of even more formidable Muslim rulers, including his son Nur ad-Din and, later, Saladin.

News of Edessa’s fall galvanized support in Europe for a new crusade to reclaim lost territories and shore up the remaining Crusader states. Pope Eugenius III’s call for the Second Crusade through the bull “Quantum Praedecessores” in December 1145 marked a more direct papal role in crusading efforts.

The Second Crusade

The fall of Edessa served as the primary catalyst for the Second Crusade (1147-1149). This massive military expedition was led by two reigning monarchs: King Louis VII of France and Conrad III of Germany, and included nobles and knights from across Europe. The crusade involved separate marches of French and German armies through Byzantine territory, leading to defeats suffered by both armies at the hands of Seljuk Turks in Anatolia. Finally, the crusaders began an ill-fated siege of Damascus in 1148, which ended in retreat and effectively concluded the crusade

Legacy

In many ways, the events of 1144 foreshadowed the eventual collapse of the Crusader states. While the Kingdom of Jerusalem and other territories would persist for another century, the fall of Edessa marked the beginning of a long decline in Crusader fortunes.